Poetry in the Expanded Field

An unclassifiable artist and a deep reader, Jen Bervin has expanded the notion of what it is to be a poet in the 21st century.

SAN FRANCISCO — I first learned about Jen Bervin when I read Nets (Ugly Duckling, 2003). In that book, Bervin took 60 of William Shakespeare’s sonnets and erased them until the words that were left (exactly where they are in the original) became her poem. In contrast to earlier poets, such as Ronald Johnson and Jonathan Williams, who erased preexisting texts, Bervin did not completely efface her source. Shakespeare’s poems are still discernible in light blue text, while Bervin’s are in black; readers can literally see the dialogue between the two poems. By leaving the source visible, she recognized that some of her poems would suffer by comparison. This is the opposite of appropriation, a common postmodern practice. Writing about this work in the afterword to Nets, she stated: “When we write poems, the history of poetry is with us, pre-inscribed in the white of the page.”

The second book I read was Silk Poems (Nightboat Books, 2017). The poem was printed like a scroll of cloth unfurling across the page; each line of the typed text (all caps) was comprised of six letters, corresponding to the silkworm’s DNA. While I knew that a physical manifestation of this poem existed, and that Bervin worked in other materials and made objects, including artist’s books, I had never seen any at this point. I planned on visiting her exhibition Jen Bervin: Shift Rotate Reflect: Selected Works (1997–2020) at the University Galleries of Illinois State University (August 15–December 13, 2020), curated by Kendra Paitz, but the pandemic made travel impossible. I wondered when I would get a chance to see an entire show devoted to the range of her practice, so I felt very fortunate to see the large exhibition Jen Bervin: Source, at Catharine Clark Gallery, in the gallery’s newly expanded space.

The exhibition’s 15 works, dating from 1998 to 2023, include artist books; “River” (2006–18), composed of silver foil-stamped cloth sequins sewn together; and “Silk Poems” (2016), an installation that features a video of Bervin’s extensive research into silk. What connects these works together is her physical and intellectual engagement with her materials, whether embroidering muslin with words and marks that correspond to Emily Dickinson’s fascicles (a group of 40 self-made small booklets in which she copied around 800 of her poems), typing up a text, or sewing sequins to form a silver, glittering river. In her practice, reading, as an enhanced, hyperconscious activity, and making become inseparable.

One of the striking things about Bervin’s work — and this is true of Nets — is her ability to both preserve and change her source. In doing so, she establishes two dialogues, one with the work and one with the viewer/reader. This is also true of early, groundbreaking works by Jasper Johns, such as “Flag” (1954–55). If we view the encaustic and collage “Flag” or Bervin’s weaving of Dickinson’s fascicles on cotton muslin only in formal terms, we miss out on the deeper and more challenging richness of their work, the dialogues they have initiated with history.

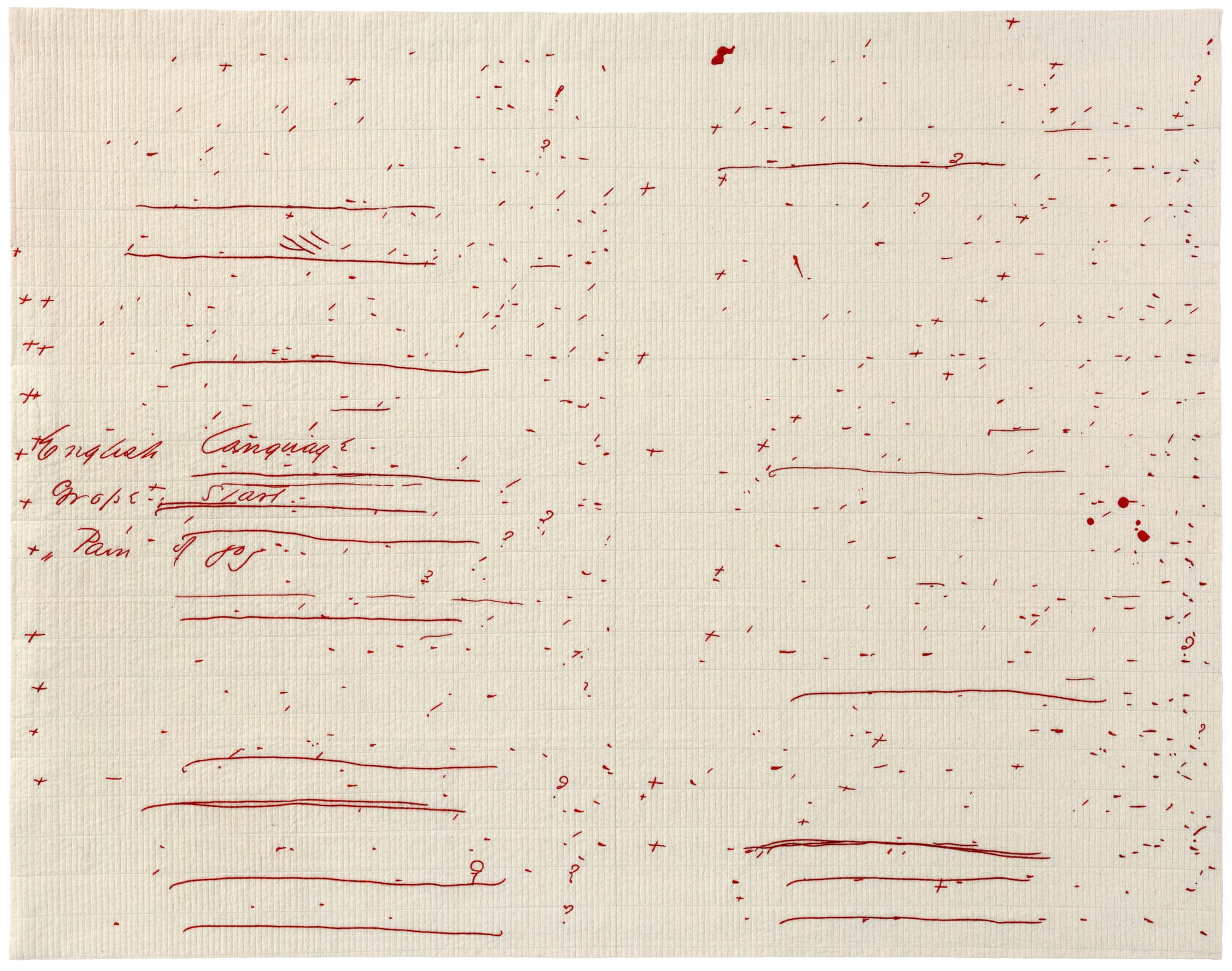

This was my experience with the group of individual pieces collectively titled The Dickinson Composites, each numbered and dated between 2004 and 2022. Made of cotton and silk thread on cotton batting back with muslin, and measuring 72 by 96 inches, they are displayed so viewers can see both sides.

During Emily Dickinson’s most extraordinary outpouring of poetry (1858–64), which coincided with the Civil War, she copied more than 800 of her poems into handmade volumes of folded sheets of paper, which she made by stabbing two holes in the papers and tying them together. Dickinson made other “signature” marks on these sheets of paper, over which scholars have puzzled. Her unique fascicles are the source of Bervin’s quirky, mysterious works. From sculptor Roni Horn to Chicago Imagist painter Philip Hanson to poet Susan Howe, Dickinson has served as source material for creators — so much so that I wondered if anything fresh could be done. In contrast to other poets and artists, Bervin does not cite, reconfigure, or meditate upon well-known lines and phrases. She is interested in the marks and dashes that Dickinson used as punctuation, which scholar have speculated as indicating pauses of silence or bridges between sections of a poem.

I think Bervin wants to suggest the background of the Civil War without being didactic about it. Cotton was produced in the 15 slave states by nearly two million enslaved people. Women made cotton clothes as well as wore cotton dresses. By evoking quilts and bedding, the artist comments on the role women played in this long, bloody conflict that still haunts us. The way red threads mark the surface, like cuts and incisions against a white ground, further inflect this reading. Dickinson never acknowledged the Civil War, nor voiced an opinion on it, slavery, or people of color.

Bervin’s touch regarding these matters is light. She gives viewers a lot of room to reflect upon these connections and silences. Her work is open-ended and resists any reductive or literal reading.

According to the press release, the sculpture “River,” which runs across the gallery’s uneven ceiling, “imagines an impossible vantage: the Mississippi River as if viewed from the core of the earth, its headwaters, alluvial path, and confluence in the delta stretching across 230 curvilinear feet of ceiling and wall.” Walking beneath the piece and looking up at it, seeing the sequins glinting and winking in the light, we are invited to recognize all the different roles the Mississippi River has played in the history of the United States. Bervin undermines our comfortable relationship with rivers, a common subject, by making viewers look up rather than down upon it.

The scale of “River” is set at one inch to one mile. In “Measure (after Susan Hiller)” (2023), Bervin pays homage to Hiller (1940–2019), the influential US-born British conceptual artist. For “Measure by Measure II” (1993–2012), Hiller burned her paintings each year and collected the ashes in glass measuring tubes. Bervin’s work consists of journals she had written between 1992 and 2012, which she burned, containing their ashes in tubes. A phrase from the journal within is on the exterior of each tube.

“Measure (after Susan Hiller)” is less visually commanding than “River” and The Dickinson Composites. I am glad about this discrepancy — it means that Bervin has not figured it all out yet. Each work is different, including her artist books. An unclassifiable artist and a deep reader, she has expanded the notion of what it is to be a poet in the 21st century.

Jen Bervin: Source continues at Catharine Clark Gallery (248 Utah Street, San Francisco, California) through June 10. The exhibition was organized by the gallery.