The Messy Family Drama of Ancient Egyptian Gods

We walk you through the incestuous, murderous, and surprisingly relatable world of Egyptian deities at The Met.

When I was seven years old, there was only one book release I cared about: Egyptology: Search for the Tomb of Osiris (2004). A scrapbook journal from a lost expedition, the bestselling children’s book nestled interactive envelopes and postcards within its illustrated pages, including a piece of “mummy cloth” and a guide to decoding hieroglyphics. I was entranced — by the textured gold and plastic gemstone cover, but also by the conceit that at least part of this history was real. I thought there truly was a missing archaeologist named Emily Sands who traveled to Cairo in 1926, and that her journals had only just been discovered for me, a girl in Seattle, Washington, to devour.

Divine Egypt, the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s special exhibition of ancient Egyptian art, returned me to a childlike state of awe and admiration for this civilization. More than 200 works spanning 3,000 years, pulled from The Met’s collection, in addition to some international loans, balance the dense world-building necessary to understand this divine hierarchy with the miracle of their artistic craft. Let me be your Emily Sands, and guide you through the messy family drama of the gods and goddesses of Ancient Egypt.

Amun-Re

The swarm of museum-goers parts like a sea at the gate of Divine Egypt before a stone statue of the god of kings, Amun-Re. He shelters the pharaoh Tutankhamun — you might know him better as “King Tut” — between his shins, his hands on the little king’s shoulders, greeting visitors with a cool stare. It’s the perfect embodiment of how this exhibition treats Egyptian deities: as idiosyncratic personalities just as worthy of our attention as the celebrity royals whose tombs we’ve visited in the permanent collection downstairs.

One of the principal deities of the New Kingdom, Amun-Re’s essence is hard to encapsulate — he is multiple gods melded together as well as his own entity, a force matching the extraordinary power Egypt reached by the 18th Dynasty. Turning the corner from Amun-Re and King Tut, we enter the complex world of polytheism (where Re exists separately from Amun-Re, a composite god).

Re

Where would we be without Re, creator of the world? You don’t need to be a fan of Afrofuturist jazz ensemble Sun Ra Arkestra to know one answer, though it’d probably give a clue. Re is the rhythm of life rumbling underneath all of Egypt. Every night, he goes into the earth to be reborn, where he must kill the snakes in his way so that he may still rise and greet us with sunlight in the morning. He appears in a Late Period–Ptolemaic Period statuette as a kind of otter-mongoose hybrid, raising his paws and smiling, wearing the solar disc headdress, ready to pounce. Felines were thought of similarly: fearsome hunters protecting those who try to nibble away at the sun god’s power.

Nut

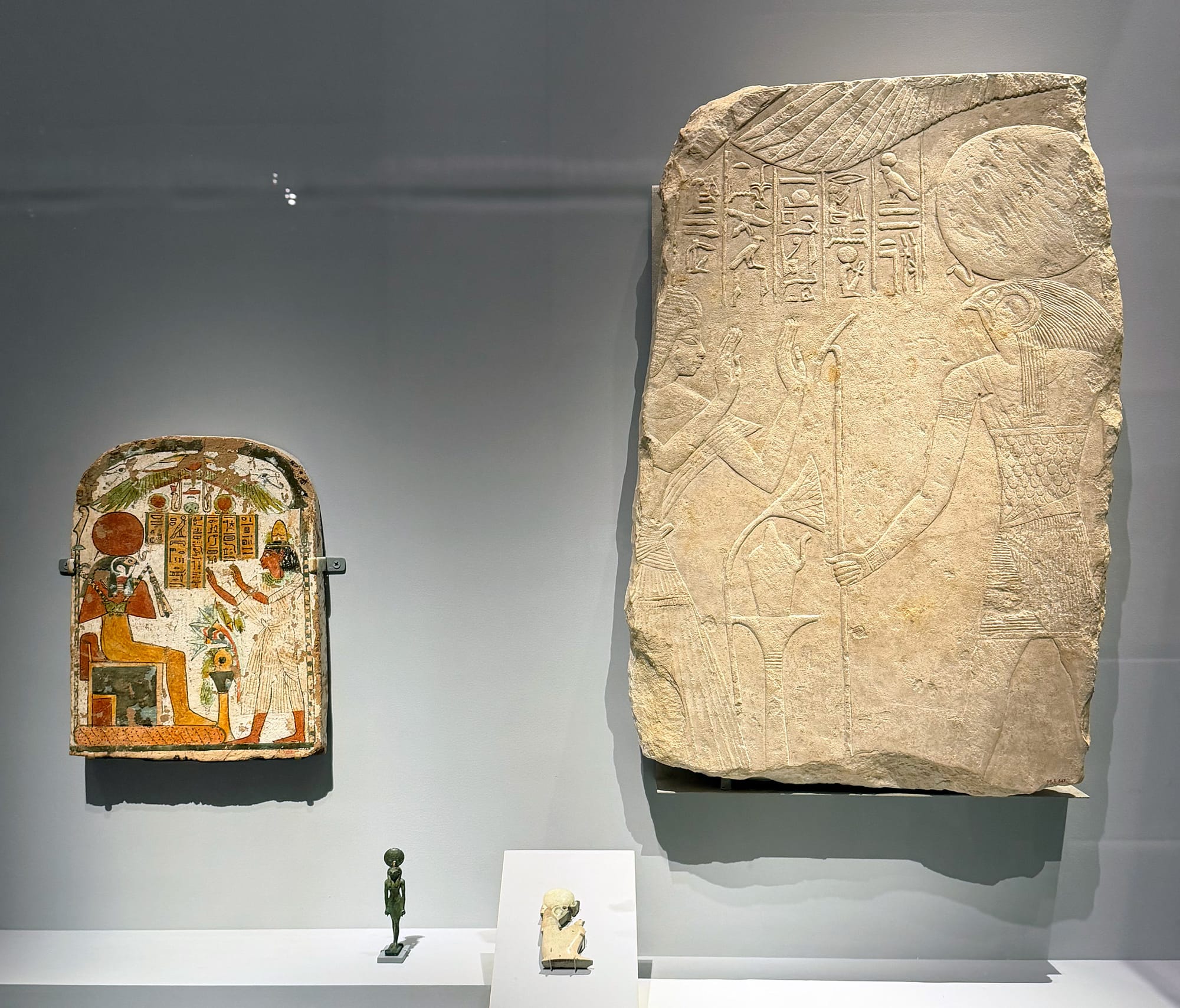

Re isn’t acting alone. In some tellings, he doesn’t just descend underground; he gets swallowed by the sky goddess Nut, who rebirths him every morning. One side gallery displays the interiors and exteriors of a well-preserved coffin, displayed vertically and encased in glass. At eye level is a naked Nut, red circles between her upraised arms and her outstretched legs, the discs depicting the sun god Re making his way through her body before dawn. Nut is associated with regeneration; she’s the tree-hugger of the group. Scholars think that a vibrant stela from around 825–712 BCE, of two men receiving water from a tree goddess, shows Nut providing sustenance to those joining in the afterlife.

Bastet

The goddess of the home, pleasure, and of the feline hunters, Bastet, is, to put it simply, dripped out. She wears a gold collar at the base of her lioness head, and gold-plated scarabs pierce her ears and nose. The cult of Bastet created and worshiped bronze effigies of the goddess, usually depicting her as a housecat sitting upright with her front legs together and tail curling around her side, a protector of pregnant women and infants. Bastet is for the cat ladies.

Thoth

If the guy selling typewriter poetry on the sidewalk outside the Metropolitan Museum were to worship anyone, it would have to be Thoth. I myself would probably worship Thoth. As the god of wisdom, the creator of languages, and recordkeeper of the underworld, Thoth is a bit of a lone, brooding wolf. His actual manifestations, however, appear as a baboon, an ibis, and an ibis-headed man. A muscled Thoth taking one step forward, as in the faience “Striding Thoth,” was a common motif in first-millennium BCE figurines and amulets.

Thoth is decidedly masculine but often sensitive and usually fair, unlike some of the gods who play favorites. When Re cursed Nut so that she’d be unable to give birth on any day of the year — because a prophecy foretold that one of her children would eventually overthrow Re — she came to Thoth, who cleverly thought to make a bet with the moon god. Thoth won the rights to 1/72th of the moon’s light, enough for five extra days in the year, allowing Nut to have five children. In the 21st century, Thoth’s legacy lives on as the name of an open-access book publishing non-profit. I think the god who once said, “Knowledge brings wisdom and wisdom is power” would approve.

Isis

Unknown maker, statuette of Isis with the infant Horus, faience (332–30 BCE)

All of Nut’s children end up powerful and important to the pantheon, but perhaps none are as popular as the divine mother and goddess of magic, Isis. She’s integrated into people’s daily lives, part of the later generation of gods who function as models of power within society and who, like mortals, wish to overcome their fates. Together with Osiris, who is her brother and her husband (yes, the Greeks have Oedipus and the Egyptians have twins who fell in love in the womb) and their miraculously conceived child, Horus, they comprise arguably the most common grouping of gods. The show ends with a small, solid gold triad in which the parents flank their son atop a lapis lazuli pedestal. Under an intense spotlight, it’s one of the shiniest and most striking objects in the show.

Upon passing this final object, visitors exit through the gift shop. Isis is the prototype for the souvenir rendering of a slender, dark-haired goddess shown in profile. She wears a calf-length skirt with triangular straps over her breasts, perhaps accessorizing with a cylindrical headdress known as the "modius of uraei" that sits between lyre-shaped horns. To give a sense of her influence, Cleopatra dressed herself like a resurrected Isis to help convince Egyptians of her right to rule. Divine Egypt has plenty of classic iterations of Isis, but curators also dug up curiosities like a metal statuette of her head, versions in which her arms meld with the tail of a scorpion, and a bookend-shaped wedge that depicts her sheltering her much smaller husband between her wings.

Seth

“No other god bears the marks of time’s march quite so visibly as Seth,” writes Niv Allon, curator of Egyptian art at the museum, in the exhibition catalog. At different times, he was worshipped as ancestor god, or else being erased, altered, or mutilated. Seth is the outcast, the runt of the litter. He’s only an important ruler briefly, after he kills his brother for the throne. He is banished, kind of — he still gets to reign over the deserts and oases. However, in solar theology, he is a fierce protector of Re.

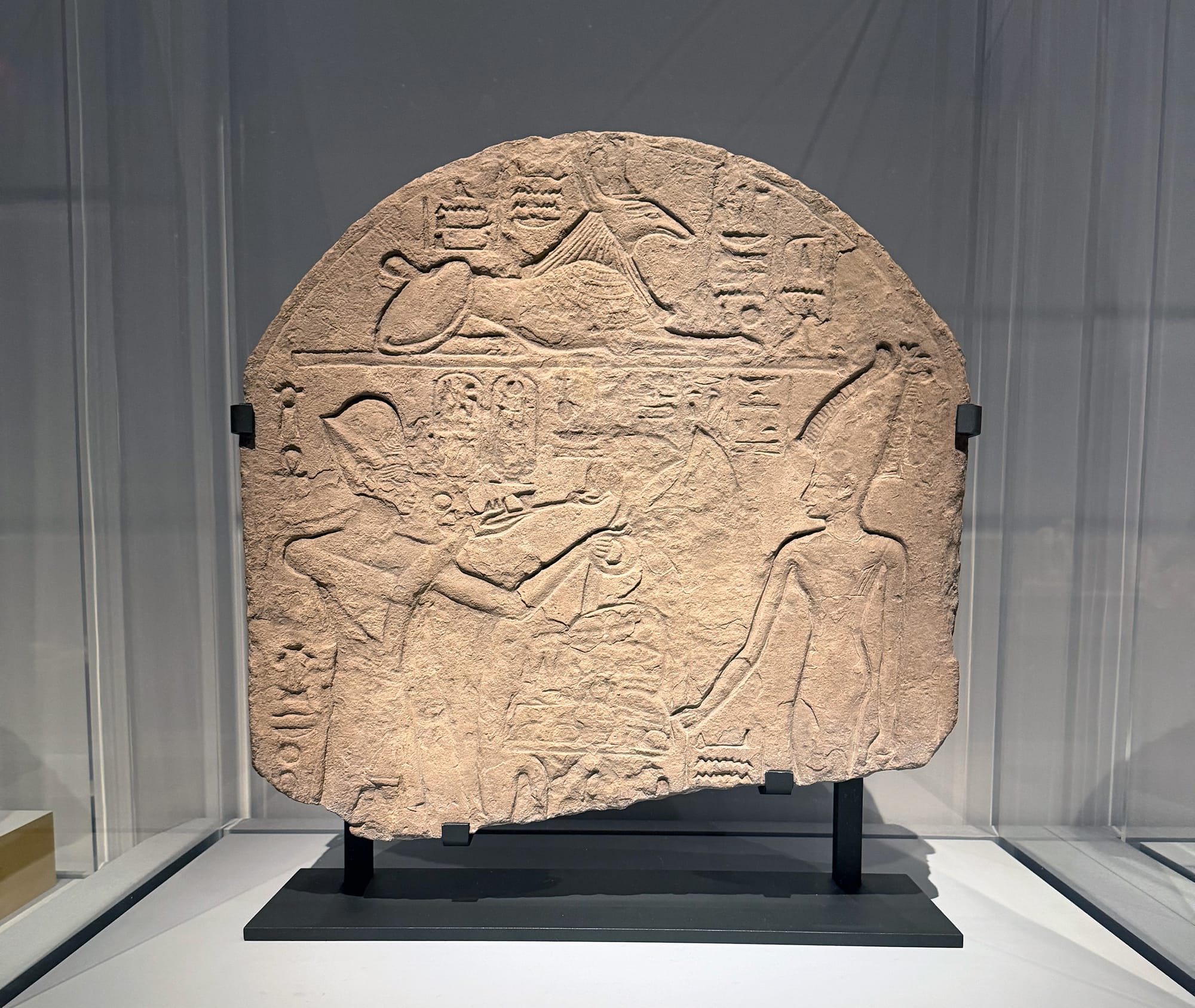

Most gods are depicted, at least sometimes, as human. But Seth always has a downward-pointing snout, pricked coyote ears, and a long tail. He usually has a scepter in hand, as in a limestone stela from 1526–1400 BCE, where he’s shown enthroned.

Osiris

The lighting in the last gallery dedicated to Osiris, god of the dead, is especially moody. The king of darkness (no relation to Prince of Darkness, the 1987 John Carpenter movie; great film) is often shown with his body fully bandaged. Legend has it that Osiris was the first-ever test subject for mummification.

We don’t see or hear too much about Osiris when he was alive, because the drama occurs in death — fittingly, he’s shown in a dark shroud here. Seth, his brother and the “god of confusion,” dismembers Osiris out of jealousy and scatters him across the land. Isis and her sister pick up his pieces and reconstruct him as a mummy. A free million-dollar idea: Dramatize Osiris and Isis in the style of Black Orpheus, the Carnaval-set rendition of Orpheus and Eurydice.

Horus

Before Osiris properly enters the land of the dead, the aforementioned goddess Isis — this time in the form of a bird of prey — hovers over her husband’s erect penis to conceive Horus, their only heir. (We unfortunately don’t get any of this visual in Divine Egypt.) Horus was raised in hiding, but when he’s all grown up, he beats Seth and wins the throne, avenging the dad he never got to meet. Egyptian pharaohs loved Horus, as he was the god most linked ideologically to the king, and they certainly loved using him to decorate. A sizable limestone double statue from the New Kingdom (c. 1343–1315 BCE) of King Haremhab and a falcon-headed Horus, together as apparent equals, exemplifies how he was often depicted. His story became about more than who he was in relation to his parents, and depictions of him also appear early in the exhibition in the foundational context of the hieroglyphic ankh (a key-like symbol symbolizing life), falcon, and sun. The eye of Horus, which comes from the myth that Seth pulls out Horus’s eye before Horus kills him, is a good luck charm that both peasants and pharaohs carved into their possessions. Think of it like a bumper sticker announcing one's proclivities for royalty and health.

Wadjet

An eye amulet isn’t necessarily an invocation of Horus. A green eye is more likely to function as a token of fertility, belonging to Wadjet, the feminine protectress of Lower Egypt said to be many things, including a daughter to Re (his “eye” on the ground) or a loyal nurse caring for an infant Horus. Divine Egypt goes kitsch with a Kushite Period statuette of a lion-headed goddess nursing a human child. But Wadjet always starts off in myths as a rearing cobra spitting at her enemies. If she is depicted as a human woman, she wears a variant of the vulture headdress in which the bird’s head is replaced by an upright cobra, as seen on a delicate Middle Kingdom lintel.

Divine Egypt dedicates a whole section to the serpents; a head recovered from a stone statue of a cobra is thought to represent Wadjet, and its abstracted obelisk shape in a sea of symbolic figuration feels eerie.