A Hair Museum Houses the Strands of Yesteryear

CHICAGO — Leila's Hair Museum in Independence, Missouri, bills itself as the only hair museum of its kind in the world. Located in the back of Leila's Independence College of Cosmetology, an unassuming storefront covered by a mirror-like material.

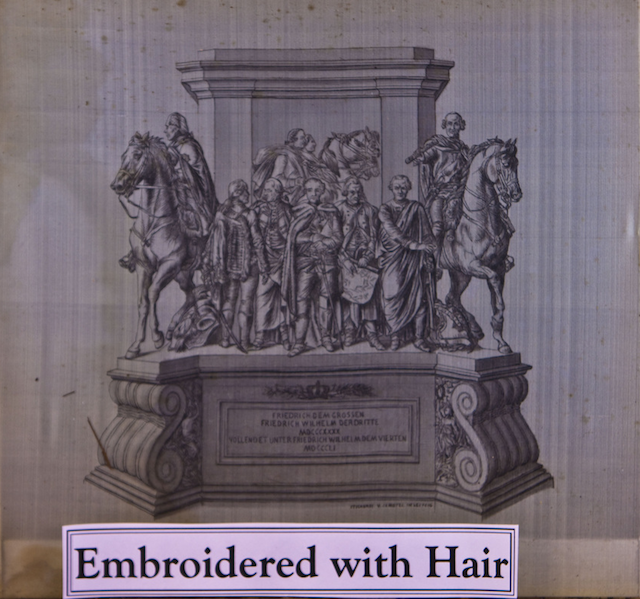

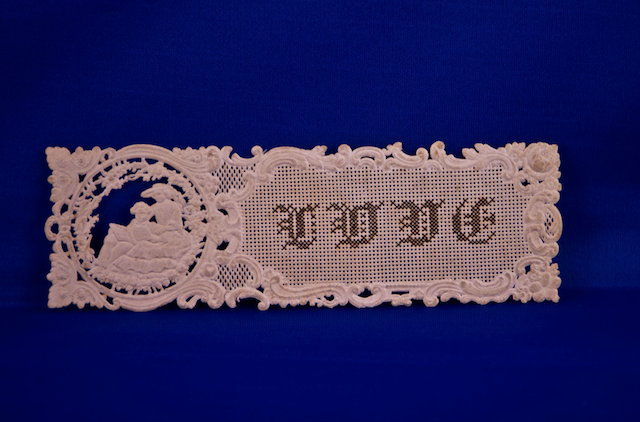

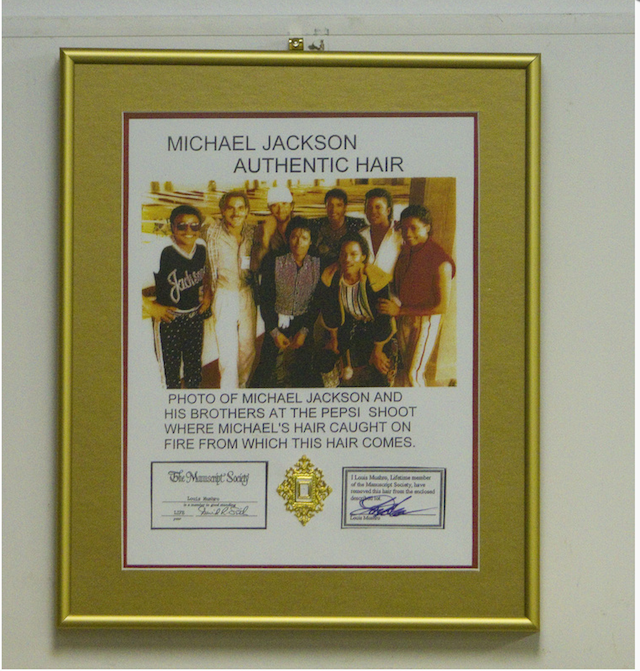

CHICAGO — Leila’s Hair Museum in Independence, Missouri bills itself as the only museum of its kind in the world. Located in the back of Leila’s Independence College of Cosmetology, an unassuming storefront covered by a mirror-like material. It is owned and operated by founder and hair fanatic Leila Cohoon, who has been a hairdresser since 1949. She started collecting hair mementos in 1956, and opened the first iteration of this museum 30 years later in 1986. The walls of Leila’s museum, now in its second and hopefully final resting location, houses thousands of hair wreaths, jewelry, and other mementos made of hair. It’s like walking through a mausoleum or cemetery, except hair is not decaying or disintegrating like the bodies already have. Hair, this snippet of the abject body, is located somewhere between life and death, yet it exists detached from its original owner.

Except there’s something decidedly more disgusting about hair than even decaying skin or fingernails, cut slices of bone overgrowth. Human hair is made of keratin and dead skin cells. Growing out of the body, it is a reminder of our own mortality — of death as a part of life, or during life itself. Like death in American culture, it too is fetishized, judged and an intimate part of one’s own identity. It’s impossible to take a long-armed selfie without getting your hair in there. Artists such as Peggy Noland who have shaved off their eyebrows are considered freakish-looking, yet fascinating for this decision to forever eliminate the option for dead skin cells growth. Find a hair in your soup when out to dinner, and you have every right to return that meal. Hair is also an signifier of one’s social status and class, and is always something that separates people by race. But it is one thing that we all share — this hair on our heads and all over our bodies. But today, it is not customary to make jewelry out of hair as was once done during the Victorian era.

This is where Leila’s Hair Museum begins. The hair pieces on display depart from the present moment, journey back to the days when hair was the only memento available. This is long before John Herschel’s first glass negative in 1839, Robert Cornelius’ daguerreotype self-portrait that same year, or any of your daguerreotype boyfriends. It’s important to remember this when wandering into Leila’s Hair Museum, where trompe l’oeil-like paintings of babies have heads covered in locks of hair. Hair become trees, flowers and shrubbery in constructed glass-dome-covered environments populated by dandy-like characters, reminding of contemporary mini-terrariums. Hair wreaths don’t need to wait until Christmas to come out; they are available year-long in memoriam to the dearly departed. Many of the hair wreaths are placed on top of a list of carefully written out family members whose hair is included in this wreath itself. These living dead remains of families are literally woven together, intertwined, and preserved for all to see. Better than an open-casket funeral or a funeral selfie, hair lasts long beyond the day of departure, preserved much like content on the internet, where the webs of relationships and familial connections happen today.

Leila’s Hair Museum (1333 S Noland Road, Independence, Missouri) is open Tuesday through Saturday, 9am to 4pm.