A Mysterious Police Archive Reveals Mid-Century Mexico's Cult Criminal Heroes

In summer 2010, while poking around at a stall in Mexico City’s sprawling thrift market, Las Lagunillas, artist Stefan Ruiz discovered a batch of photographs from the city’s police archives.

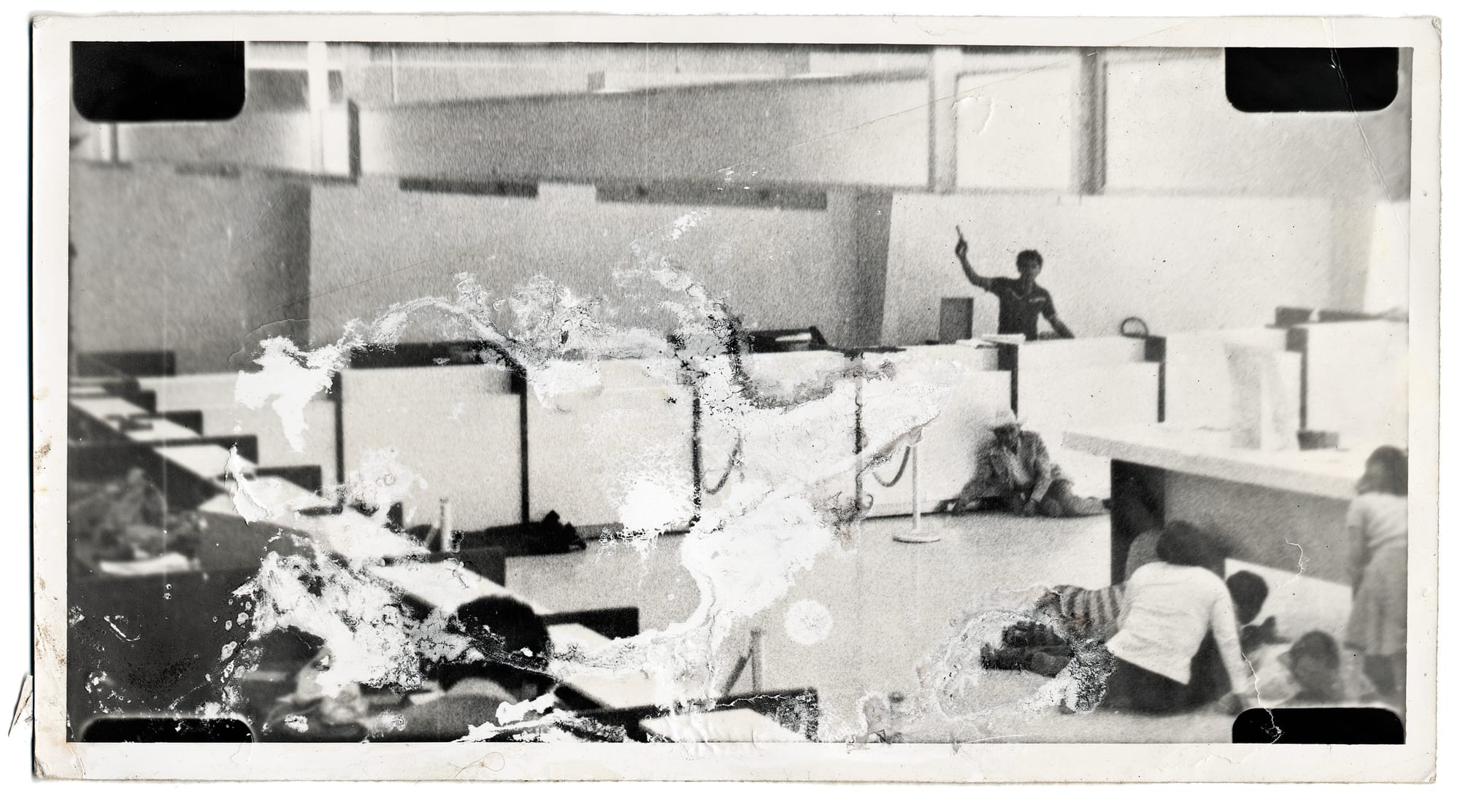

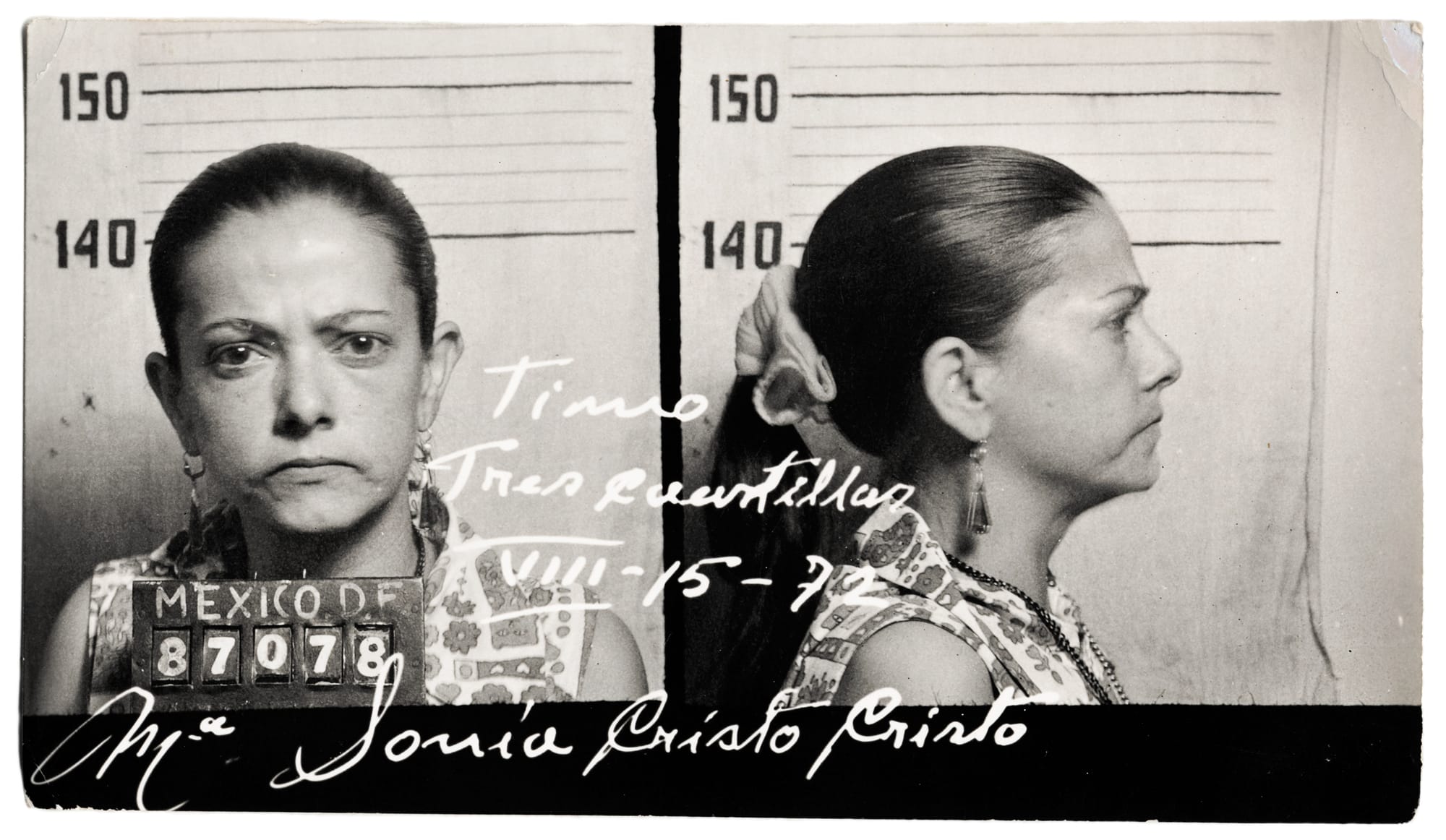

In summer 2010, while poking around at a stall in Mexico City’s sprawling thrift market, Las Lagunillas, artist Stefan Ruiz discovered a batch of photographs from the city’s police archives. Over the next few years, Ruiz purchased hundreds more such photos from the vendor, who refused to reveal his source. The yellowing black-and-white images included mugshots, stills of an armed robbery, and artists’ impressions of both notorious criminals and stolen jewelry. Ruiz was fascinated by this rarely seen visual history of crime in mid-century Mexico. Now, his collection is compiled in a book, Mexican Crime Photographs, published by GOST.

Stemming from stories of social revolutionaries like Pancho Villa to brutal images from contemporary Mexico’s drug war, there’s long been a “link between Mexico and a particularly violent brand of criminality in the U.S. and European popular imagination,” as Benjamin Smith, an associate professor of Latin American history at the University of Warwick, writes in the book’s introduction. “Yet, beyond these stereotypes, crime has played a crucial role in the way that twentieth-century Mexicans have experienced their everyday lives.”

Unlike what’s shown in the news, the images in Mexican Crime Photographs are not filtered through any media lens, offering a rare insider perspective on the individuals behind this history of crime. The stories behind each photograph mostly remain mysteries, so the mugshots start to resemble portraits of desperation, fear, and defiance — not just government documents. They’re also portraits of cult heroes, as certain non-violent thieves gained a kind of respect among some Mexicans. These Robin Hood figures “reprised the roles of the Revolution’s social bandits,” Smith writes.

Thanks to the economic inequality that plagued the country after the Mexican Revolution, robbery was mid-20th century Mexico’s most popular crime. “Criminals committed crimes not because they had any natural or racial proclivity, but because they were poor and desperate,” Smith writes. Taken from the 1950s to the ’70s, the mugshots here mostly picture thieves of various orders: carteristas (pickpockets); asaltabancos (bank robbers); paqueros (swindlers); and criadoras ladronas (nannies-turned-thieves). There are only a few photographs of murderers in the collection, as murder rates dropped in the ’50s and ’60s.

The criadora ladrona María Elena Romero Carmona was one of many poor thieves who had her first-person life stories regularly printed in crime magazines. Carmona wrote of working as a servant for a rich woman in Xochimilco for years, until the day two thieves forced her to hand over the house keys. “Despite her innocence, the police landed her in jail, claiming she had masterminded the whole event,” Smith writes.

Such poignant stories elicited sympathy from readers and changed national attitudes towards crime. In magazine Guerra al Crimen’s “Usted es el juez” (“You are the judge”) column, readers wrote in “to disclaim a justice system, which punished these victims of Mexico’s unequal social hierarchy,” Smith writes. In the 1960s, certain non-violent criminals enjoyed celebrity status. The most notorious included Heriberto Aguir Acevedo “El Elote” or “The Sweetcorn,” who stole the pistols from Mexico’s medal winning Olympic marksman; the pickpocket José Rodríguez Torres “Cuatro Vientos” or “Four Winds,” who stole President López Mateos’s wallet; and master housebreaker Efrain Alvarez Montes de Oca “El Carrizos” or “The Reeds,” who in 1972 robbed jewels from the house of the sitting president, Luis Echeverria. These “noble thieves,” as tabloids called them, dressed to the nines and dined in the finest restaurants.

Fifty years later, the photographs in this collection seem a comparatively innocent precursor to the stories of police corruption, violent crime, and prison escapes that dominate the news. “Outside the mainstream media, Mexico’s marginalized continue to respect select members of what elites deem the criminal class,” Smith writes. “The days of the gentleman thief like El Carrizos or El Elote may have passed. Narcos, like Joaquín ‘El Chapo’ Guzmán, are the new popular heroes.”

Mexican Crime Photographs from the archive of Stefan Ruiz is published by GOST Books.