A Virtual Quilt of Remembrance for Mexico's Murdered Students

Last November, news from Mexico about the 43 missing students from the Ayotzinapa Rural Teachers’ College in Guerrero captured international attention.

Last November, news from Mexico about the 43 missing students from the Ayotzinapa Rural Teachers’ College in Guerrero captured international attention. But predictably, it quickly fell into the background as the media cycle moved on, and the more cynical among us may have wondered if anyone had actually cared at all.

The New Yorker staff cartoonist Victoria Roberts and mixed media artist Andrea Arroyo — both Mexican Americans — wanted to find a way to get people interested in the story again. “I thought it was very important to keep an international focus on the loss of lives in Mexico,” Roberts explained recently to Hyperallergic. “I reached out to Andrea for help, and she suggested doing a virtual quilt.”

Together, they organized the Tribute to the Disappeared Virtual Memorial Quilt, a massive, crowd-sourced project that takes its inspiration from the AIDS Memorial Quilt. “The AIDS quilt really changed people’s perception of the disease from being a gay men’s issue to a universal one,” Arroyo said. In the same way, the women hope their quilt will show people that human rights violations in Mexico aren’t just a problem for Mexicans, but for everyone who wants a safer, more just world. “Art is a fantastic tool to create bridges between communities, and to humanize issues that may seem too distant or too unfamiliar for some,” she said.

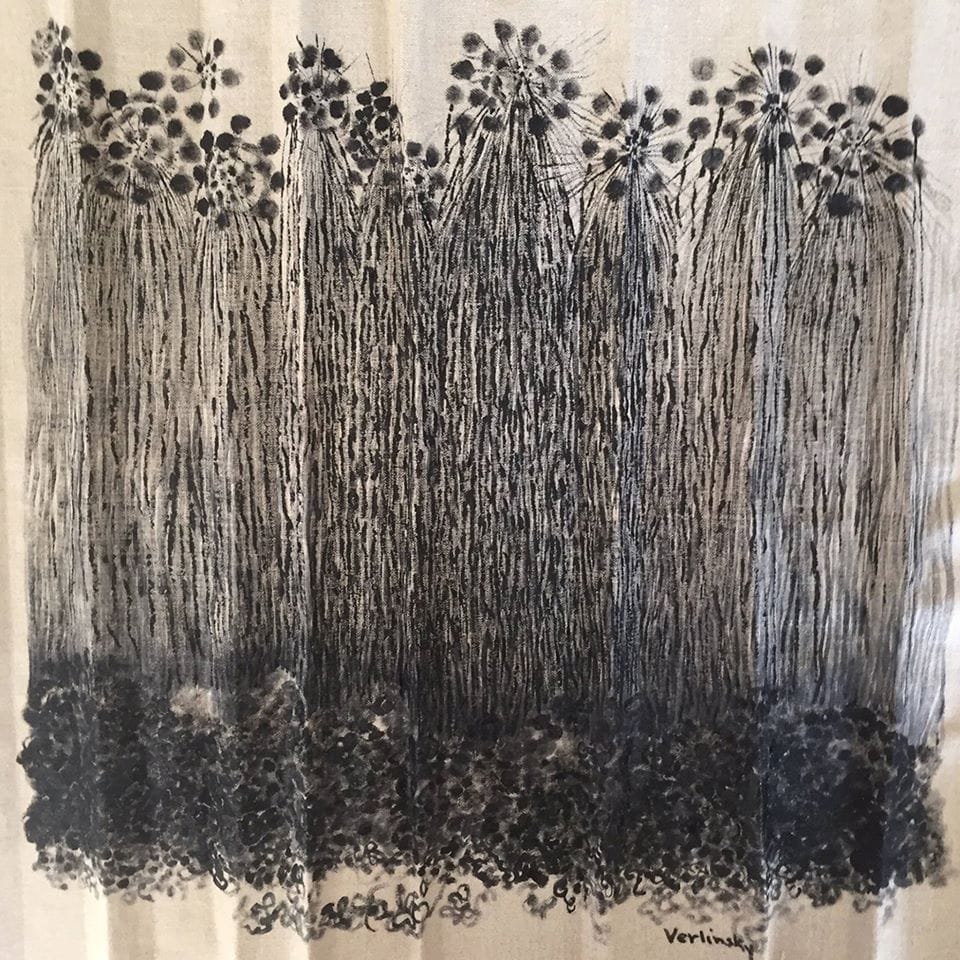

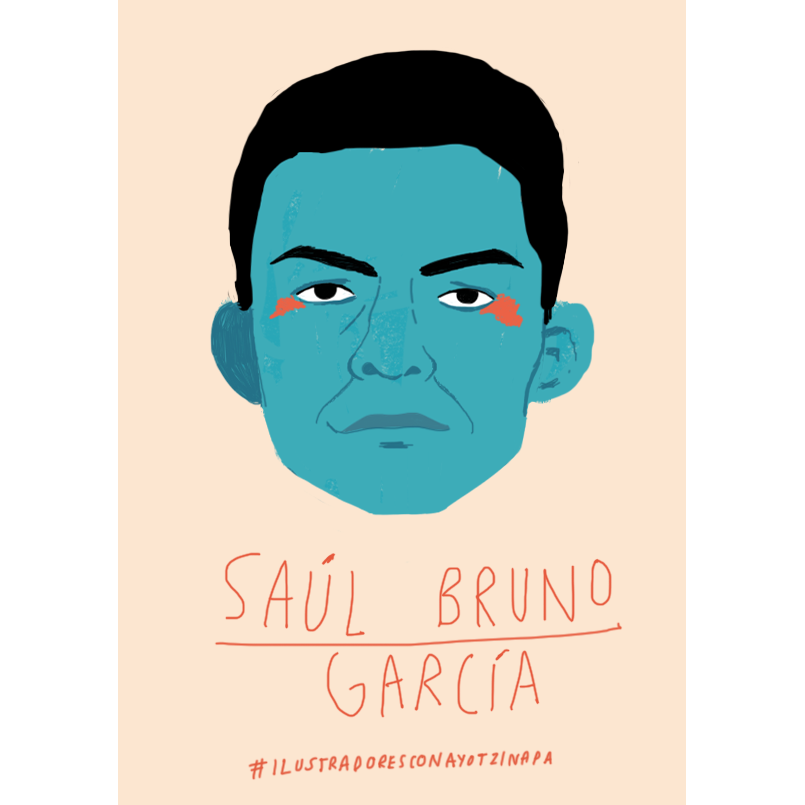

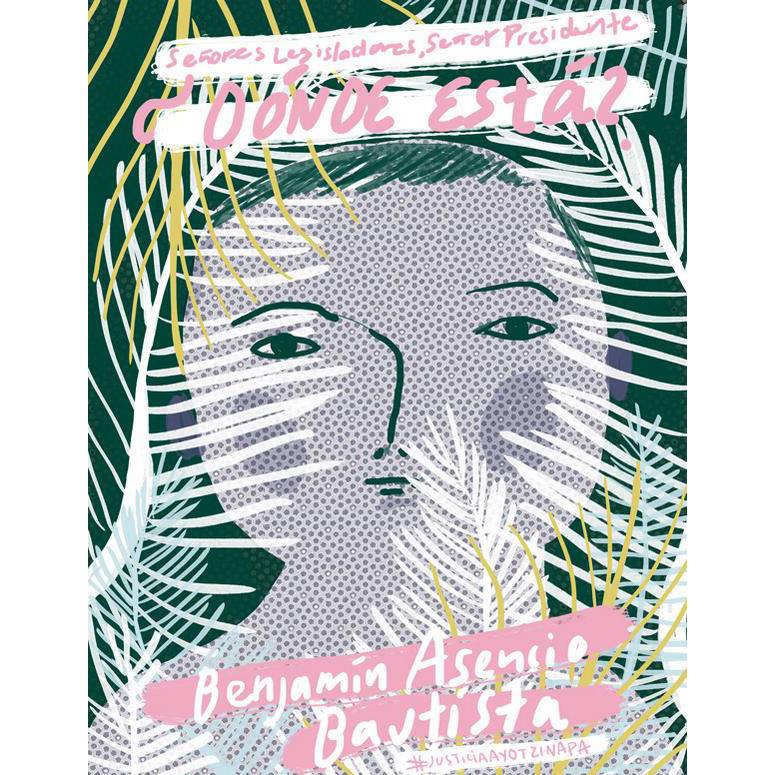

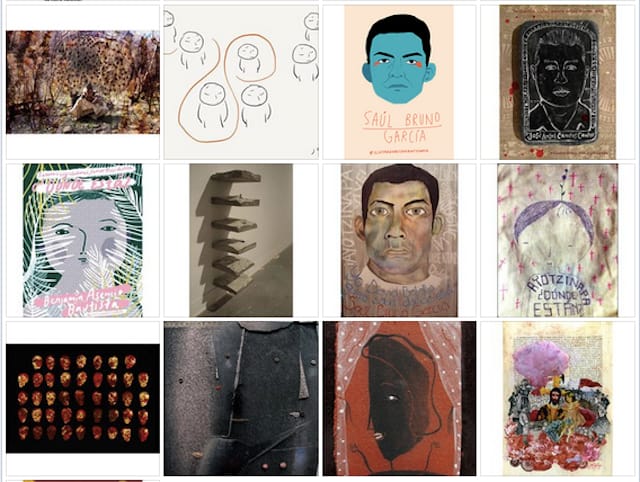

The project invites artists around the world to create work responding to the tragedy and submit their images. The resulting jpegs comprise the “squares,” which are digitally pieced together in the gridded, collage-like way that images are displayed on social media sites. “It’s an ideal format because it allows me to constantly include more and more artists from around the globe, since the images can be sent electronically,” Arroyo, who manages the quilt’s Facebook page, said. So far, more than 200 artists in places as far away as Greece, Peru, India, Scotland, and Taiwan have submitted art, and new contributions pour in every day.

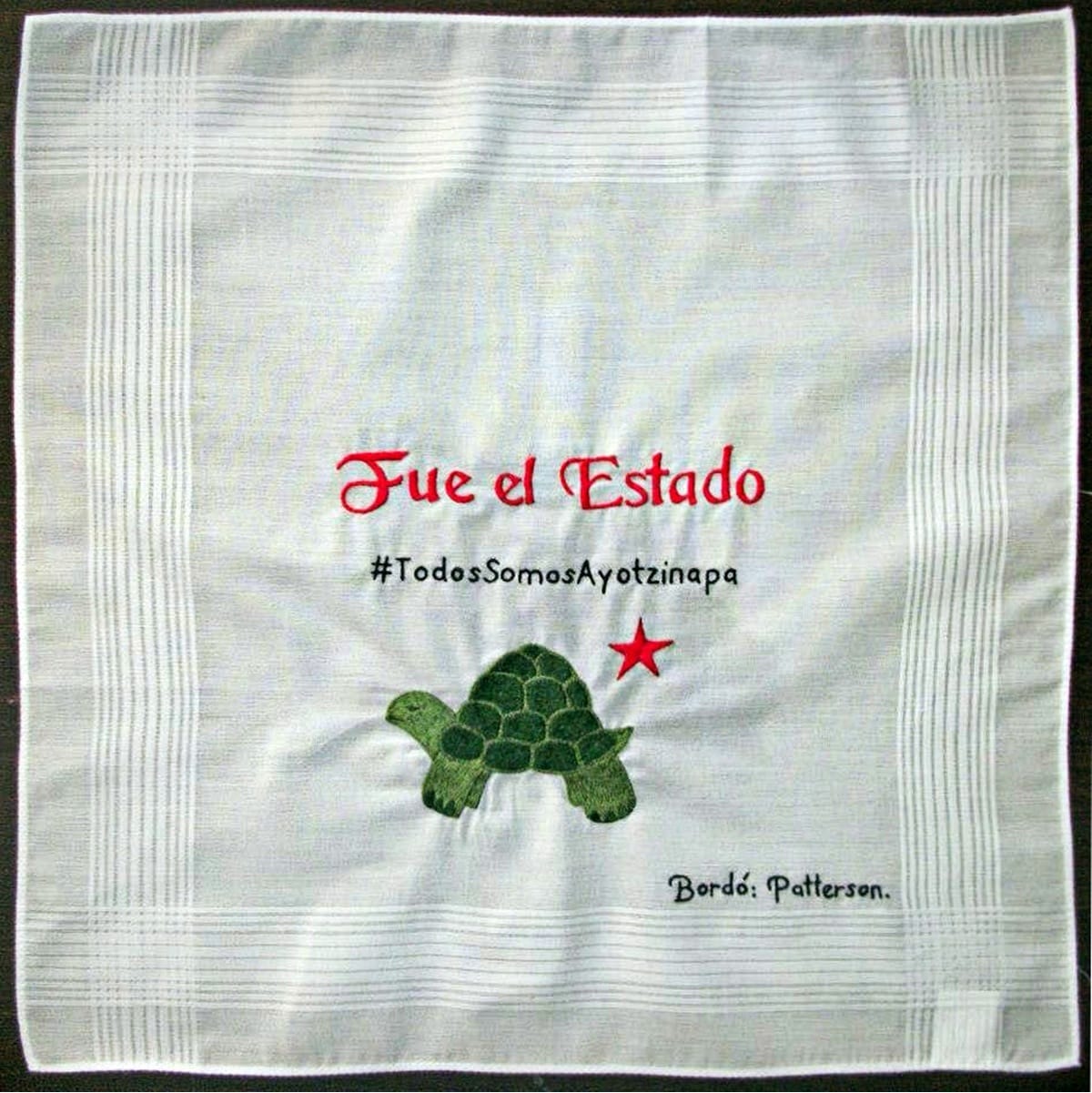

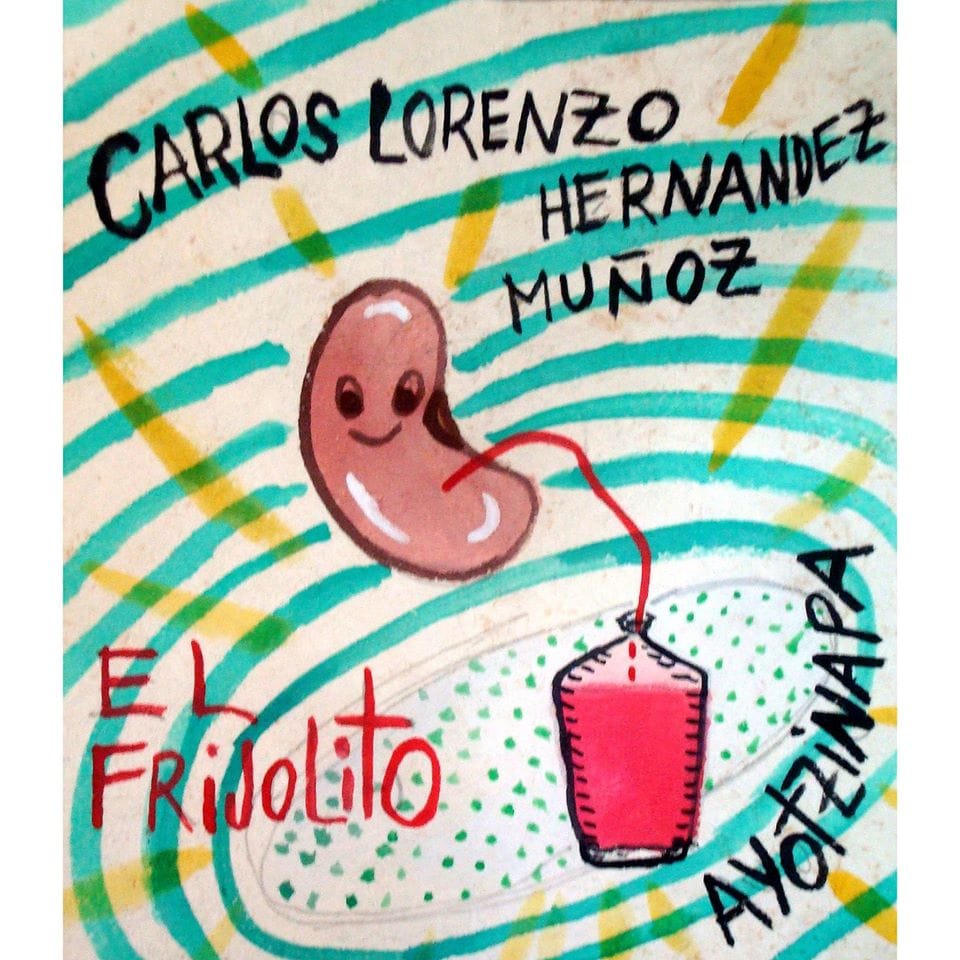

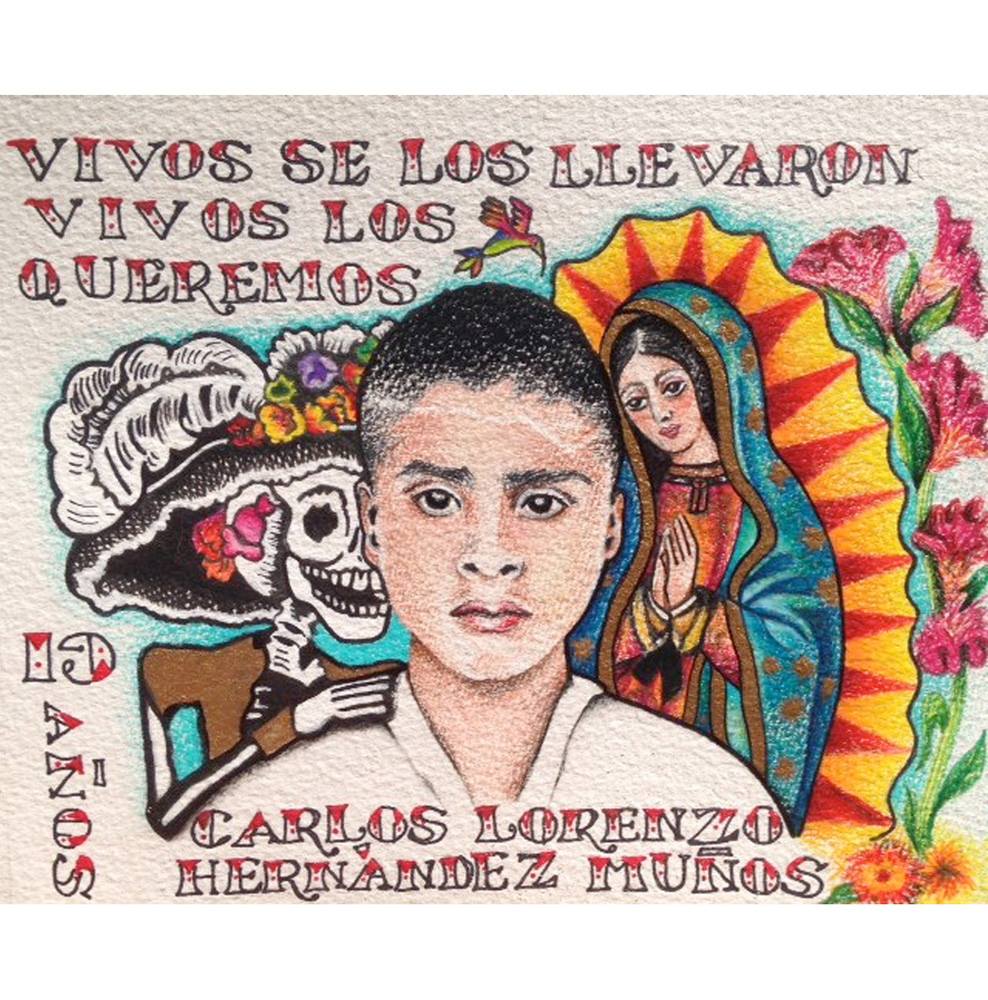

The works are just as diverse in medium as the nationalities of their makers. Australian artist Laura Patterson submitted a series of embroidered handkerchiefs — intimate objects that were likely carried in the pockets of some of the students; one features the hashtag #TodosSomosAyotzinapa above an image of a turtle (Ayotzinapa means “The Valley of the Little Turtles”). Mexican artist Antonio Gritón contributed 43 separate mixed media paintings that draw on the personal histories of each of the boys to create a unique homage; one, titled “Carlos Lorenzo Hernández Muñoz (7/43),” depicts a smiling red bean above Muñoz’s nickname, “El Frijolito.”

Arroyo’s own contribution was an impromptu performance she did weeks after the disappearances. Armed with rolls of paper, markers, string, and a list of the 43 students’ names, she boarded a subway train to attend a demonstration at Union Square. On the way, she found herself writing the names of each boy on a strip of paper and, on arriving at her destination, asked participants to help finish the rest. She then pinned them together and wore them as “wings” on her back. Illuminated by the street lights, they made Arroyo look like a guardian angel. Today, the image brings to mind the lack of protection the young men suffered at the hands of the local police; just who is watching out for Mexico’s youth today?

“While the political speeches and actions are valuable, for me, connecting through an art piece proved incredibly moving and efficient, and it got me thinking about using art to engage a larger community in the issue of human rights,” Arroyo said.

Building on the virtual quilt, Roberts and Arroyo have conducted art workshops in New York at La Casa Azul and the New School that are meant to foster awareness and healing; they’re planning new ones in the upcoming weeks at Columbia University and Mano a Mano. They also hope to show some of the work in an exhibition this September on the first anniversary of the students’ disappearances.

“Art is a universal language, and I truly believe the project has the power to bring international attention to the human rights crisis in Mexico,” Arroyo said hopefuly. “This attention may in turn pressure the authorities to begin addressing the issue of the students from Ayotzinapa and the widespread culture of injustice and impunity.”

“It’s hard to gauge what effect these projects have, but this is what I can do,” Roberts added more cautiously. “Everyone must do what they can. It is important to act. The sum of these actions, however small, makes a difference.”