Acts of Cruelty Captured by Citizens

New Documents at the Bronx Documentary Center is not necessarily the most conceptually elaborate exhibition, or the most aesthetically alluring, but it is the one show I've seen this year that makes crucial sense of our contemporary compulsion to document sociopolitical upheavals and state-sponsored

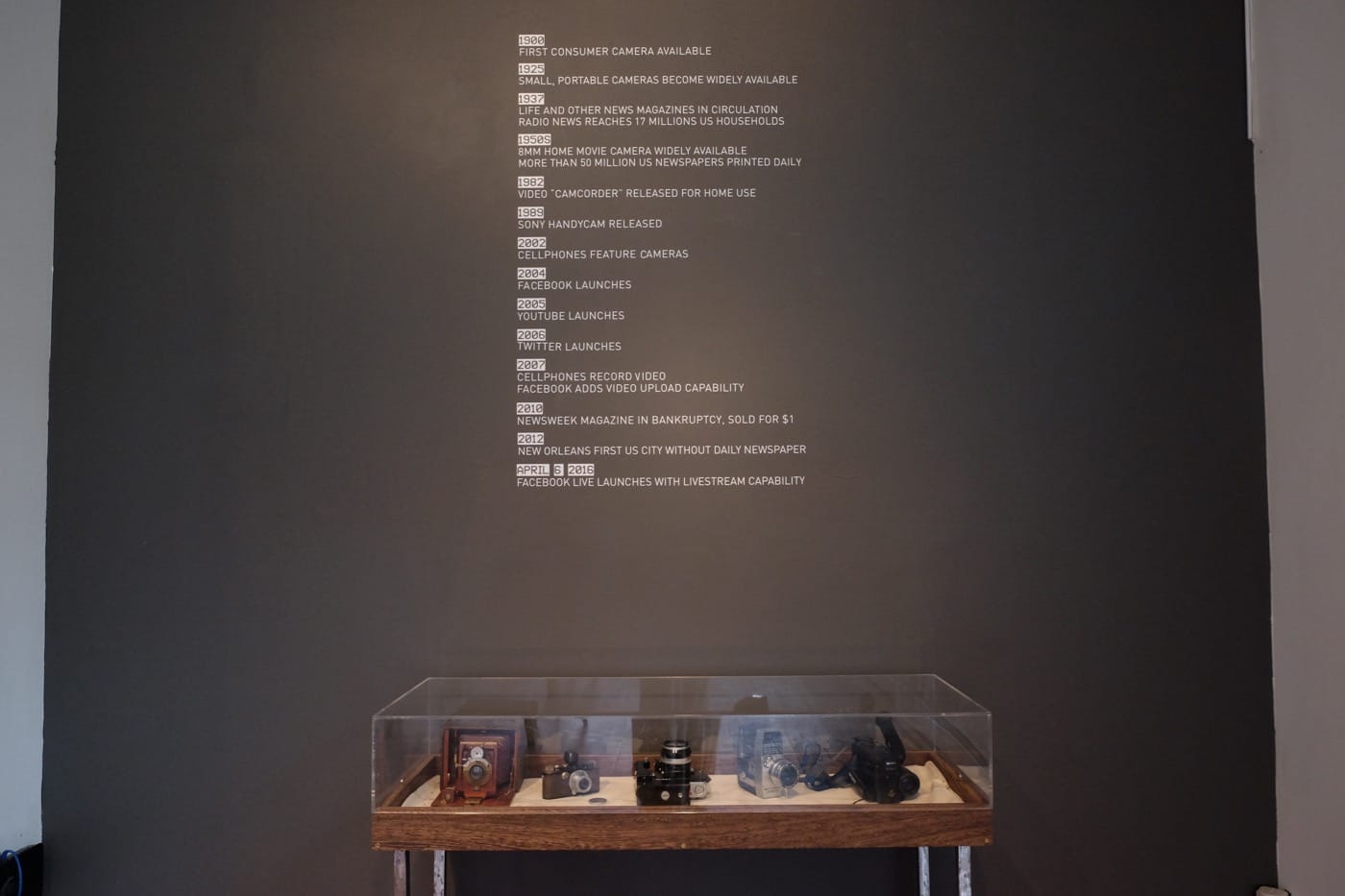

New Documents at the Bronx Documentary Center is the most important exhibition I’ve seen all year. It’s not necessarily the most conceptually elaborate, or the most aesthetically alluring, but it is the one art exhibition I’ve seen that makes crucial sense of our contemporary compulsion to document sociopolitical upheavals and state-sponsored violence. New Documents is also the most moving show I’ve experienced — yet it avoids being overly sentimental. It presents critical historical moments when pedestrian observers documented some atrocity, or crisis, or clear failure of public policy that, without that visual record, would likely have been resolutely disputed by official actors and information channels, and become tangled up in the knots of hearsay, accusation, and counter claims. Not the eyewitness accounts, but the images of a North Charleston police officer calmly shooting a fleeing Walter Scott in the back are what galvanized public consciousness to an ongoing problem at the core of our culture. Indeed, the images in New Documents are harrowing — they depict death and dying, assault and terror, and still they arm us. They equip us to see the world as it is and not merely as we wish it to be.

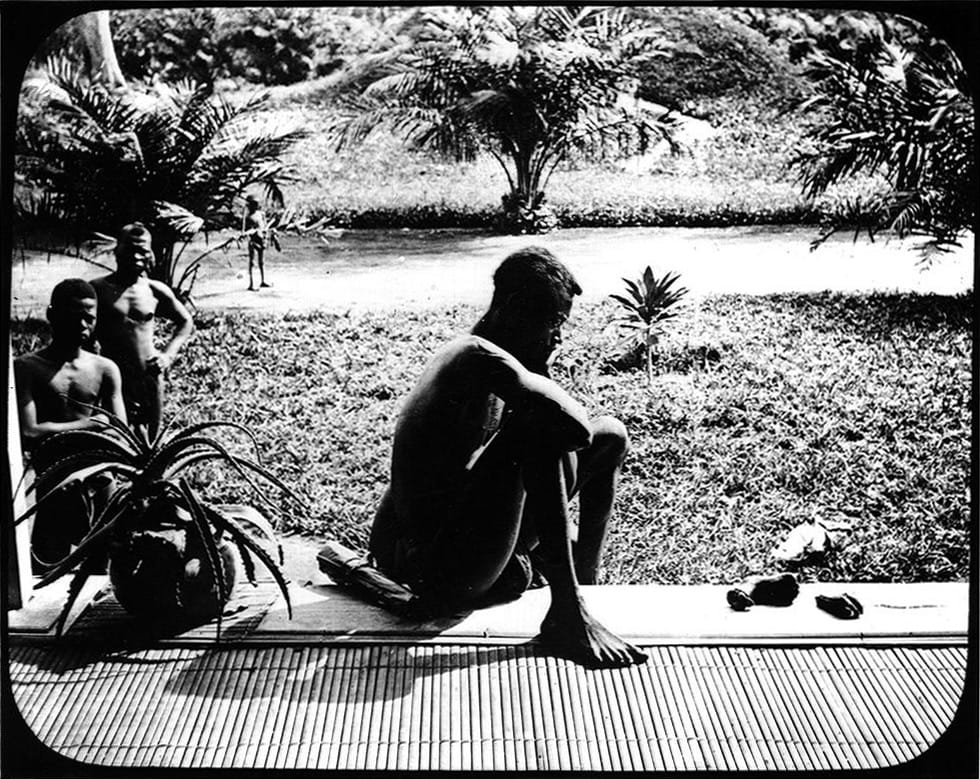

There are many ways to navigate this exhibition; the way I did was by paying attention to hands and arms. If you look in this way, you see the emphatically gesticulating arms of Eric Garner before he is pinned beneath the New York Police Department officer who would eventually kill him; you see the bloodied, awkwardly bent arm of Philando Castile, still constrained by his passenger-side seat belt; the arms of Antonio Zambrano flailing upward as he falls beneath gunfire from police, who killed him in 2015; the arms of the UC Davis students seated on the ground during their protest in 2011 are folded in tight, the hands not visible as Lieutenant John Pike methodically douses them with pepper spray. There are hands in the air waving hats at the protests held in response to the suicide of Mohamed Bouazizi in Tunisia in 2010, at the start of the Arab Spring movement. I saw a group of hands pressing fervently on the head and chest of Neda Agha-Soltan, who, despite the desperate ministrations, soon bleeds out after being struck by a stray bullet during protests in Tehran in 2009. You will already have seen the unforgettable footage of the police savagely beating Rodney King after a car chase in Los Angeles in 1991. You are reminded of how the batons are often swung with two hands; the arms rise and fall and rise again, with obscene frequency. And then, lastly for me, was the rending image of a man in 1904, living in the ironically named Congo Free State under the rule of Belgium’s King Leopold, looking at the severed hand and foot of his five-year-old daughter.

I learn again and again, through watching each vignette, that our cruelty to each other is astonishing, and that one of the few mechanisms that might check that impulse is the possibility of having each unconscionable act documented and seen. If you care at all about the relationship between documentation, imagery, and political power, you need to see this show. Mind you, the videos and pictures likely won’t be news to you. You will already be very familiar with these images because of the 24-hour news cycle and their endurance on the internet. But seeing them all together, the force of their content builds cumulatively, to the point where I regard our basic survival as not being predicated on obedience to authority, and not even on the crucial act of recording acts of atrocities, but rather on luck and happenstance. Despite living in ostensibly civilized societies, we are subject to raw, raging violence, sometimes at the hands of those sworn to protect us.

New Documents at the Bronx Documentary Center (614 Courtlandt Avenue, South Bronx) is on view until September 18.