Alternative Rock Gets a Reboot

Trading in activism, self-awareness, and intimacy, four alternative guitar-rock albums manage to revitalize familiar forms.

Alternative guitar-rock is in a pickle these days — less because there’s been so much of it over the past several decades than because so much of it has been critically acclaimed and all the referents are too obvious. The four albums reviewed below demonstrate varying strategies for how to revitalize familiar forms, often with startlingly marvelous results indeed.

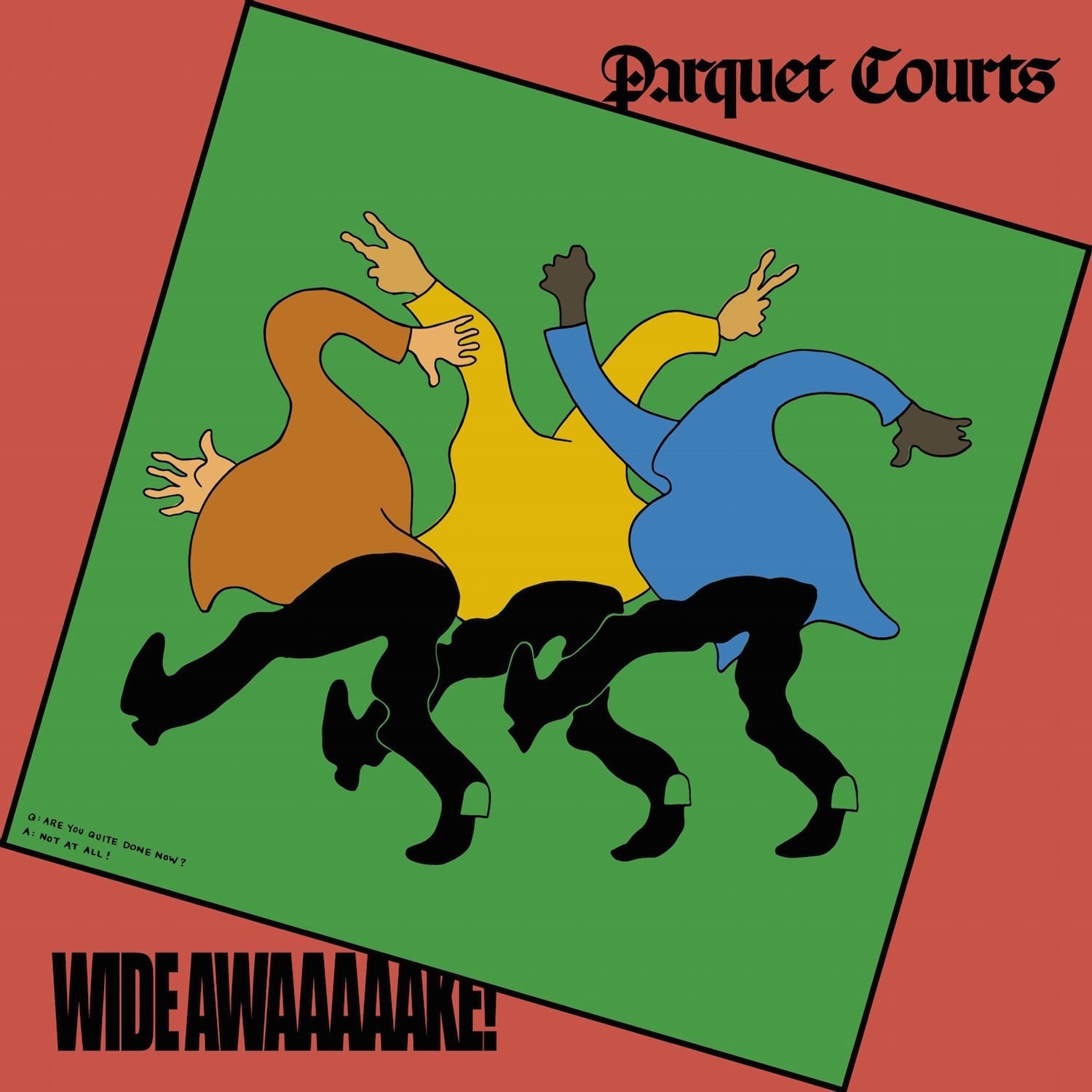

Parquet Courts: Wide Awake! (Rough Trade)

This decade’s most ambitious and accomplished garage rock band has topped itself with each album over the past five years, without diverging from garage rock’s current social purpose, asking: how does garage rock speak to the world now? This protest album, whose title signals the band’s embrace of an explicitly political anger few bands have dared with since the election, offers an answer.

The two opening tracks are likely the most scathing, skewed political punk songs that will emerge this year. “Total Football” is a jumpy, upbeat anthem with a hyperactive bassline, framed on each end by a slower, power chord-driven march. “Collectivism and autonomy are not mutually exclusive,” bellows Andrew Savage at the end, in raw admonition. Next is “Violence,” a jagged groove whose circular guitar riff keeps sinking its teeth into splattery drums, intermittently interrupted by pitch-corrected, artificially deep, evil cackling and a high keyboard squiggle in the style of Bernie Worrell; the song is centered on the slogan “Violence is daily life.”

The rest of the album can’t top such firebombs, but the lyrics stay on theme. With smoothing touches and sonic filigrees courtesy of producer Danger Mouse, Parquet Courts havee expanded their musical template, augmenting their chunky, jaunty guitar grooves with ominous keyboard effects, dreamy waves of amplifier feedback, angular funk riffs, and, on “Back to Earth,” an accordion-esque synthesizer that flips the song on its head. These days outspoken protest songs are as old-fashioned as guitar-heavy alternative rock, and the conjunction of aesthetic and political futility toughens the songwriting, because it inspires the venting of cathartic energy.They rage against their own powerlessness, insignificance, and the unlikelihood that a political punk album will make even a tiny difference.

Although the archly bemused tone of their earlier music persists, in the congested vocals especially, expanding their repertoire from obscurantist guitar-rock to rousing, left-leaning, funk-inflected guitar-rock means they’re now unifying multiple traditions. As students of history, the synthesis must please them.

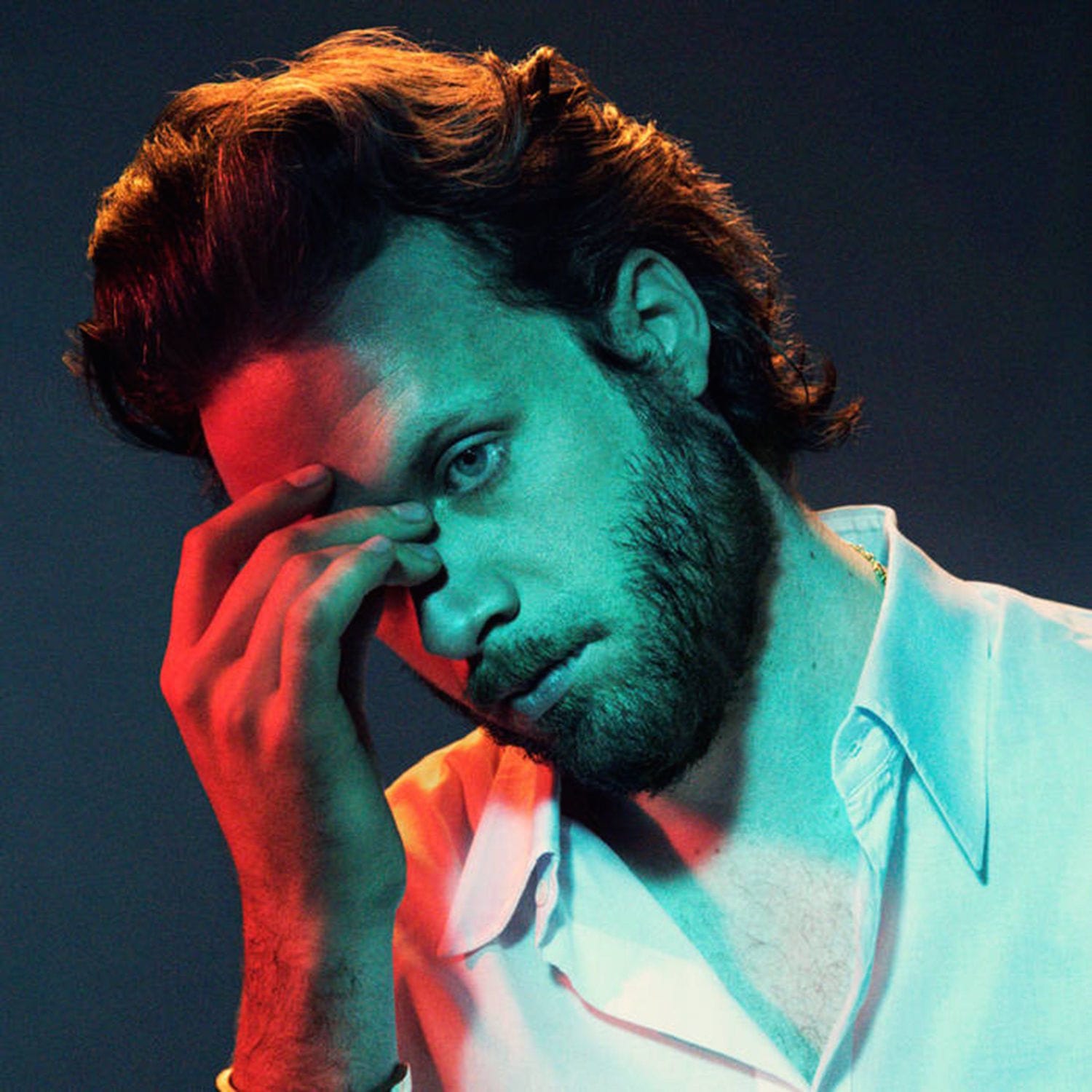

Father John Misty: God’s Favorite Customer (Sub Pop/Bella Union)

Father John Misty presents himself as the Randy Newman of the current media-saturated nightmare age, an edgy satirist working in a deceptively smooth, polished studio-rock format. Here, he goes meta (again?), tackling weighty themes like self-loathing, benders and destructive spirals, the pros and cons of the Father John Misty persona (well!), and the miracle of love.

Last year, Misty bestowed upon us the most overweeningly self-involved social critique of our time. On the condescendingly titled, tepidly performed Pure Comedy, Misty’s well-groomed designer folk-rock band failed to rise above a lachrymose crawl, thus sparing listeners the burden of feeling musical pleasure while absorbing the artist’s lofty proclamations on social media, the entertainment complex, outrage culture, and other hot topics lesser writers have at least the modesty to sneer about in quickly digestible think pieces, rather than an hour-plus album.

He’s learned his lesson, for the sequel’s songs are briefer and snappier. The strummed acoustic guitar, plinky pianos, sighing, honey-coated backup singers, and sparingly deployed horns and glockenspiel equal a consistent band sound. His melodies have brightened, too, as on the amused, spinning “Mr. Tillman” and the furious “Date Night.” His lyrics here have taken an introspective turn; this is the kind of album that tempts critics to use superlatives like “most personal.”

“Mr. Tillman” and “The Palace” both paint a scenario where he’s secluded in a hotel, having a mental breakdown, trying to hide from the outside world while he drinks alone; elsewhere he admits that playing the Father John Misty persona — performing, period — has gotten to him, and he’s suffering under the weight of his artistic pretensions.

This self-reflexive turn is perhaps the only remaining option for an artist who’s cultivated an image of self-awareness, which doubles as a defense against criticism: of course he knows what he’s doing, all the ironies are intentional, he’s deliberately trying to make himself look ridiculous, goes the argument. However many meta-layers he applies, though, the core appeal of his persona lies in a tired ideal of solitary male genius, and the limitations of this pose strip his songs of political bite and emotional substance. On the album’s final song, as the piano keys bash, he has a sudden magical epiphany: “People, we’re only people/there’s not much anyone can really do about that.” I’m delighted his personal development has taken him this far.

Frankie Cosmos: Vessel (Sub Pop)

Over the past decade, Greta Kline has recorded hundreds of quiet, spiky folk-punk songs about romantic and existential anxiety, the geography of New York, and the beauty in small details, whether on official studio albums or on dozens of Bandcamp-exclusive releases. Spanning 18 songs in little over half an hour, this album feels emotionally larger, as the small parts click into a stately whole.

Kline’s wobbly, crackling music projects an illusion of vulnerability so fragile, so unassumingly intimate, these songs inspire suspicions even as they tug on the heartstrings — surely candor of expression alone would not be enough to conjure such an effect, and indeed it’s not. It’s a function of the related lo-fi illusion, the impression that these turbulent, punkoid spurts, airy, strummed confessionals, and squelchy, through-composed amalgams of both were stitched together by hand, that she’s sharing something private with you (and you alone, dear listener!).These are familiar tricks arranged in novel combinations. It takes formal expertise and a strong knowledge of the human psyche to dramatize insecurity so adeptly.

The album sticks in one’s ear partially because of Kline’s softly messy sonic signature, mixing electric guitar chug with acoustic guitar lilt to conjure breezy, rickety, restless forward motion. Partially, it’s her small, shaky voice, and the casually matter-of-fact way she sings seemingly momentous admissions while flattening the vowels, finding frivolous ways to rephrase ordinary feelings (“Making a list of people to kiss/the list is a million yous long”). On the cozy, chirpy “My Phone,” the slight echo accentuating her singing radiates delighted relief, while on “Apathy” her breathy double-tracked voice over bitter guitar crunch shivers with nervous resignation. Projecting a gracious playfulness no matter the mood, she clatters and skids through the aural space, hanging on tightly to her guitar.

As a compulsive miniaturist and prolific songwriter, given to fashioning oodles of tiny individual gems, she likes to mess with tempo and song length. The variety lends the album a depth beyond its homemade scope. Often, the shortest songs ache as tenderly as the big statements. The minute-long “As Often As I Can” goes, in its entirety: “I love you so/I let you know as often as I can.”

Snail Mail: Lush (Matador)

If the many young, sad, demotic female singer-songwriters currently populating indieland constitute an informal movement, as Jia Tolentino has claimed in the New Yorker, it’s a traditionalist movement, stealing verities like jangly guitars and confessional misery from Cat Power’s shadow and reclaiming them for the present day. Snail Mail put a languid twist on these virtues, distilling the universal melancholy ache into a quasi-breakup album with an inscrutable poker face.

What distinguishes Snail Mail from many similar bands combining minimalist guitar-pop and wryly forlorn heart-songs is their deadpan musical stance: Lindsey Jordan’s dazed, droning, mildly off-key voice, uttering every statement, whether happy or sad, self-mocking or defiant, in the same indifferent drawl. The band’s melodic sense, too, squashes tunes that might have soared, instead sending them plodding over square drumbursts and chugging chords that move bluntly along. The band’s deliberate impassivity masks bits of dynamic guitar playing, as on the brightly distorted riffage splintering apart at select moments on “Heat Wave” or the translucent rhythm hook descending in an endless spiral on “Golden Dream.”

Theoretically, the band’s detachment conjures emotional depth by contrast, making a show of apathy to suggest hidden feelings; the awkward clunk is meant to evoke a wounded heart in shy retreat. “Pristine” is a vicious portrait of silent infatuation, as Jordan moans a series of flushed, embarrassing admissions she knows she’ll never have the courage to speak aloud, with her need to be noticed by the special someone outranked only by her need to stay invisible forever; the guitars thunder in place, mirroring this emotional paradox as closely as they can. Elsewhere they fizzle, sinking into a sluggish enervation that suggests they’ve taken their own band name literally. Such are the dangers of overdoing a compensatory stance.

Slightly too poky, the album nonetheless delights in its demonstration that reticence and catharsis are not mutually exclusive. Aiming for epic adolescent romantic melodrama, they instead capture the grating cadences of standoffishness in electric detail.