An Anthropological Look at Weapons of War as Objects of Art

The Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard explores centuries of weapons from around the world that double as works of art.

CAMBRIDGE, Mass. — Two examples of Tlingit hide armor are positioned side-by-side at the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology. One is beautifully painted with formline clan art, while the other is plainly colored, with several rows of Chinese coins sewn above puffin beaks. Both were collected in the 19th century by the Harvard University museum, but represent a transitional period when Russians were arriving in Alaska with guns, and the indigenous people had to rethink their weaponry traditions in the face of this tool of carnage.

Arts of War: Artistry in Weapons across Cultures features the Tlingit armor among 170 objects from the Peabody’s collections. Curated by Steven LeBlanc, an archaeologist and former director of collections at the Peabody, the exhibition explores centuries of weapons that double as artistic objects. Some of the decorative traditions represented here were developed for aesthetic purposes, such as the gemstones embedded in a Balinese blade or prehistoric Nazca spear-thrower decorated with a carved cat.

Others were more utilitarian. For instance, Western Australian wooden shields were grooved with zig-zagging patterns to disorient their foes, not dissimilar from the later “dazzle” camouflage on World War I ships. One of the exhibition’s most intriguing displays features body armor from the Kiribati on the southern Pacific Gilbert Islands. The armor is formed from coconut fiber, and accompanied by a spiky helmet made from a whole puffer fish and a sword inset with shark teeth, an intimidating example of transforming the natural world around you into an outfit of war.

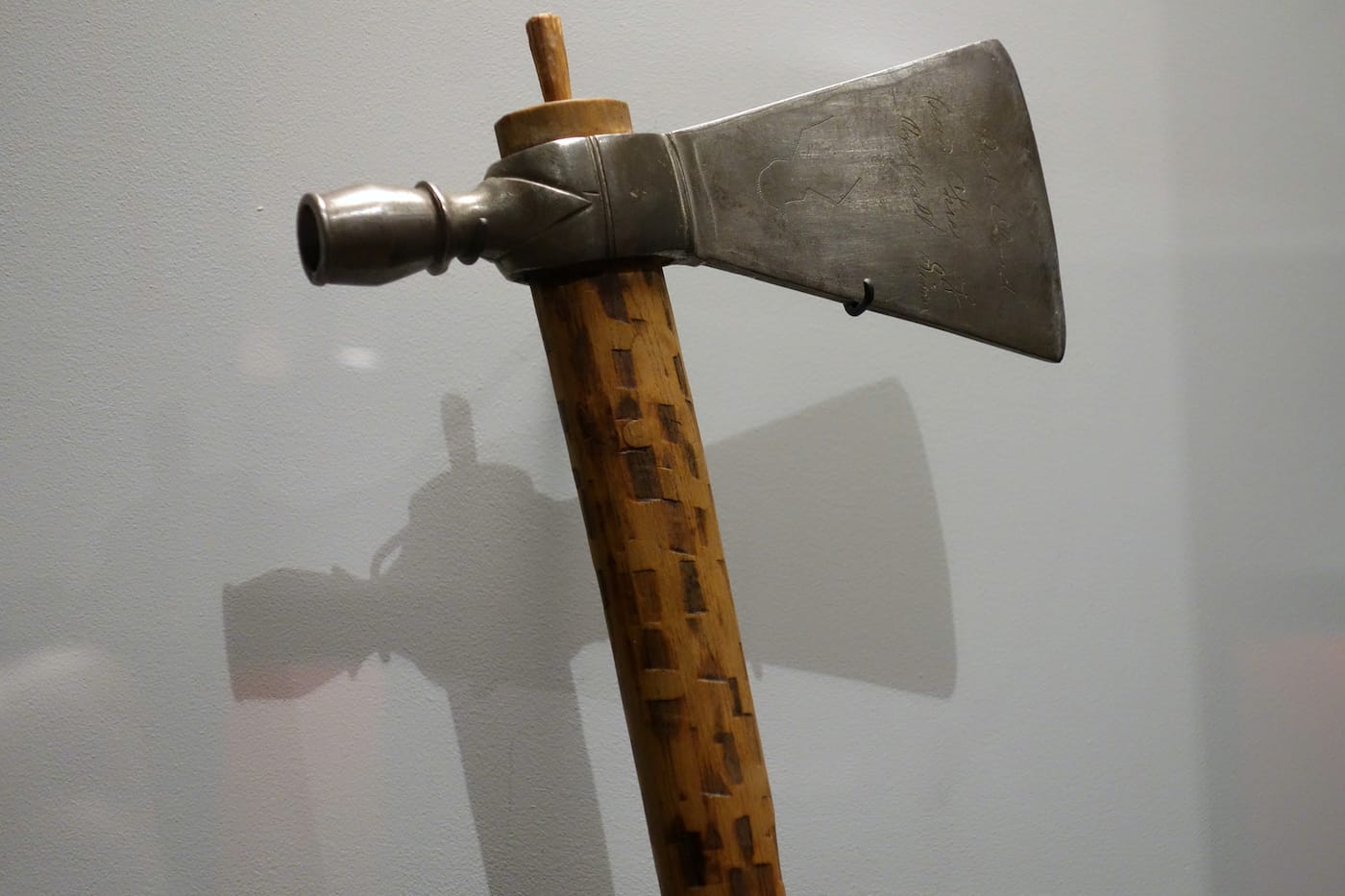

As the Peabody is among the world’s oldest anthropology museums, the pieces on view are impressively global, coming from every continent aside from Antarctica (which has yet to have its first war). It’s also interesting to see these objects — many, like the Tlingit armor, collected in the 19th century when the colonizing cultures were amassing the very weapons they were rendering obsolete — reframed in a wider consideration of human ingenuity in the face and service of violence. There are only a couple of items related to peace in the exhibition, one being a wampum belt from Northeastern Ontario, the other a pipe-tomahawk that is believed to have belonged to Red Cloud of the Oglala Lakota. As an indigenous leader in the 19th century, when his people were being relocated onto reservations after battles with the US Army, the shape of the pipe as a bludgeoning weapon seems appropriate to its complex place in time.

Visitors outside of Cambridge can explore selected objects through an accompanying online exhibition, which additionally allows museum goers to zoom in on details without leaving nose smudges on the museum cases. For a relatively small show, it’s impossible for the exhibition to cover all of human history, and it doesn’t go into great detail on how the Industrial Revolution and development of things like tanks and bombs made all of these spears, shields, swords, and suits of armor obsolete. There’s just a hint of the mechanized brutality. A rare gun in Arts of War is a revolver made in Austria with ornate silver work, a delicate touch that carried some traditional craftwork onto this increasingly fatal device.

Arts of War: Artistry in Weapons across Cultures continues through October 18 at the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology (Harvard University, 11 Divinity Avenue, Cambridge, Massachusetts).