An Artist Draws the Women of the War on Terror

Artist Sofia Niazi is a Londoner, born and raised. But in a post-9/11 world, Niazi has been troubled by how her city and her country have changed, by how people in her community are being treated.

Artist Sofia Niazi is a Londoner, born and raised. But in a post-9/11 world, Niazi has been troubled by how her city and her country have changed, by how people in her community are being treated. England, like many Western countries, has targeted Muslims, adopting sweeping surveillance tactics and instigating investigations based on fear. Niazi’s recent series Women of WOT (2014) and Videos of WOT (2014) are the results of her confronting that tension.

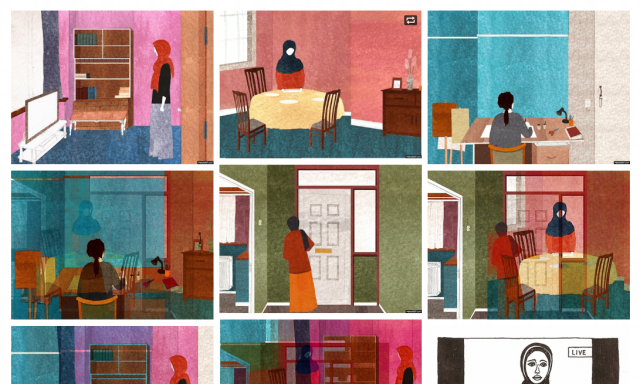

Both series document Muslim women left behind by their arrested, fleeing, or deported husbands. Women of WOT consists of animated GIFs showing stories that go largely untold — the quiet pains and absences experienced by these women. Browsing through the GIFs, you get the unshakable feeling that this silent pain is cumulative; the ghosts of the War on Terror become increasingly visceral as the images progress.

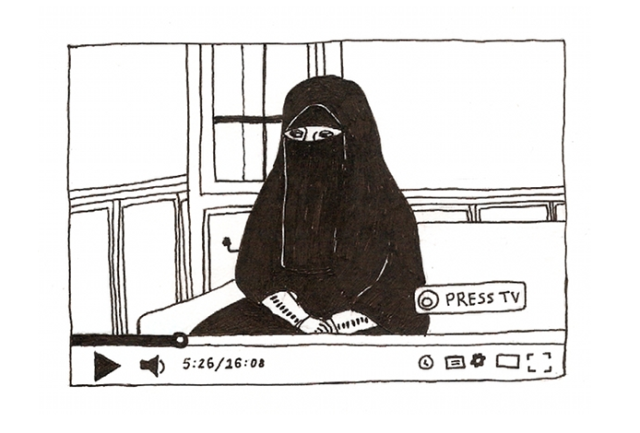

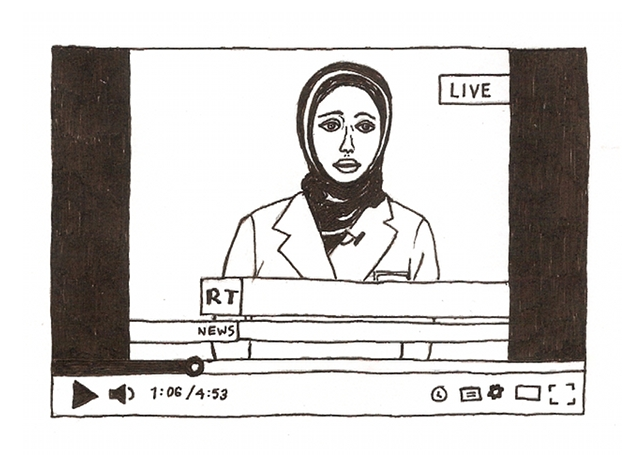

Videos of WOT is a keen investigation of how the media depicts Muslim women. Niazi creates Illustrated stills that link back to original news videos, placing the artwork in dialogue with the “real” interview and broadcast footage in a unique way. Here she entwines the disparate roles of storyteller, documentarian, activist, and artist in a subtle and beautiful way.

As editor and co-founder of One of My Kind, a print and online publication celebrating the work of women (particularly Muslim women), as well as curator and a co-founder of the East London festival DIY Cultures, Niazi has worked with a diverse array of creatives, political groups, and collectives. Because I’m nearly as much of an outsider to Niazi’s experiences as possible, I reached out to her over email to ask her to talk more about her work.

* * *

Ben Valentine: The sense of a great absence and silence is palpable in these works, and what drew me to them. Can you talk about that?

Sofia Niazi: I think depicting a person alone in a room will always create a sense of silence and distance, maybe because we’re seeing someone who is alone with their thoughts, a place we can’t reach. I looked at a lot of paintings when I was working out how to compose the images, and two artists whose work really stood out were Edward Hopper and Vilhelm Hammershøi. Their paintings of women in rooms really captured a sense of solitude.

For me the sense of absence in the works is about two things: the absence of a solid identity and emotional absence. I intentionally avoided depicting any of the women’s faces, because from the book Shadow Lives it was clear that for a lot of the women privacy was very important. I also wanted to draw attention away from the specificity of the women and focus more on the relentless and difficult situations people have found themselves in. I tried to convey a sense of emotional absence through the stillness of the women. I imagined that in the face of such lengthy uncertainty, you would have to develop a degree of absence and numbness just to keep going.

BV: What inspired you to make this work?

SN: I’ve known about a lot of the cases for a while and the way that the accused and their families are portrayed and dehumanized through the media is something that has really troubled me, as I’m sure it has many other people. There are so many different ways of highlighting, articulating, and communicating struggles and injustices. I felt that there was something that illustration could bring to the table, so that’s why I made this work.

BV: What is your relationship to this women of the War on Terror community?

SN: I don’t know whether there is a women of WOT community as such. There are so many different types of women who have been caught up in the “war on terror” — women of different generations, cultures, locality. Some of them are the spokesperson for their family struggles; others are just trying to cope with their situations and retain some sense of privacy. While I know some of the people who have been directly affected by injustices brought about by the “war on terror,” I think it’s a big mistake to look at them as exceptions. The new “anti-terrorism” measures that allow for people who are deemed “suspicious” to have all of their rights stripped and, in some cases, even their citizenship revoked is something that affects an entire community. While these measures are being exercised on Muslims today, tomorrow they could easily be extended to any or all other parts of society.

BV: What is a defining experience you’ve had since 9/11 that might be emblematic of this period?

SN: There are so many things — just the fact that it’s so normal to a see a double-page spread in a newspaper with various stories dedicated to anti-Muslim scaremongering is something I can’t get over. If there was one moment, though, I’d say it was when Gary McKinnon was spared US extradition on the grounds that he has Asperger’s syndrome while Talha Ahsan was extradited days later despite also having Asperger’s. To me it any cleared up any doubts I had about whether a two-tiered justice system has emerged post-9/11.

BV: I see you’ve done illustrations for the Guardian and the Museum of London. What role do you feel art plays in the news and politics?

SN: I like the way that it’s very obvious that art is someone’s interpretation of something. When we read the news and listen to politicians talk, sometimes we assume we’re getting some facts or some sort of truth and don’t realize that they too are often just giving interpretations and mediating experiences. In that sense I think art provides a space for nonofficial voices to emerge, and perhaps encourages people to interpret things for themselves instead of relying solely on others.

BV: Do you see your art as activism? Do you believe and hope that these works can make real changes for these women?

SN: I see it as protest art, since it’s concerned with activist campaigns to bring about justice for families and victims of the war on terror. I feel that art has a specific role within activist movements: the ability to articulate the sentiments of a larger group or movement and the ability to communicate and inform people about certain issues. But I think it’s just one link in a much bigger chain. I hope my work makes it clear that the injustices brought about by the “war on terror” and the suffering of the people affected is not going unnoticed.

BV: You’ve worked with a wide range of political and cultural groups. Can you talk a little about your community and the intersections of race, religion, and art in London?

SN: There are a lot of interesting things happening in London. There seems to be a new generation of London-based groups and collectives who are exploring issues surrounding race, religion, and identity. The Black Feminists, OOMK, Sorry You Feel Uncomfortable, Lonely Londoners, and The Body Narratives are just a few of these projects that are putting on events and exhibitions exploring these intersections.

OOMK, which is a magazine I work on, was motivated by the importance of visual communication and the lack of representation of Muslim women and ethnic minority groups in the creative industries. DIY Cultures, a daylong festival celebrating the spirit of independence and autonomy, was started by myself, Hamja Ahsan, and Helena Wee as a way of creating a meeting point for different autonomous and independent projects and groups, and also as a place to openly discuss and contextualize topical issues surrounding police brutality, the industrial-prison complex, and misogyny, amongst many other things. Hamja spent many years campaigning against the US extradition of his brother Talha Ahsan. He programs the talks at DIY Cultures and uses it as a platform to connect many of the family campaigns and activist groups he worked with over the years.