An Artist Persists in Syria in a Time of War

HONG KONG — What does it feel like to be an artist as the art and architecture of your culture is systematically being obliterated?

HONG KONG — What does it feel like to be an artist as the art and architecture of your culture is systematically being obliterated? For Fadi Yazigi, bearing witness becomes an act of resistance, as well as catharsis. He, along with some 100–150 other Syrian artists, are still creating work inside Damascus. They have remained despite the lack of a viable art scene.

It wasn’t always this way. Starting in the 1950s and 1960s, Syria developed a thriving government-funded arts program at the Faculty of Fine Arts at the University of Damascus, admitting a varied student body from all over the country and emphasizing forward thinking. Influenced by lush late Ottoman styles as well as French colonialism, the mid-century modernists from the region commonly referred to as the Middle East defined a certain aesthetic, but Syrian artists changed their focus to highlight a plasticity of brushwork and a more subdued choice of color.

Syria enacted national economic reform right around the millennium. Fueled by a rising market from the rapidly developing Gulf art scene, Damascus blossomed from 2004 to 2011. Numerous commercial galleries and nonprofit art spaces sprouted, and Christies and Sotheby’s contributed to the fervor by setting up new outposts, first in Dubai in 2006, then in Qatar in 2008. But since the Syrian civil war began in 2011, brought about by the uprisings of the Arab Spring, all art activities have ceased. They’re “very rare,” Yazigi told me on a visit to his current solo show at Yallay Gallery. “Before, everyone is meeting. Now I feel I have to be here [Damascus] to document what is going on. I go out, go to the studio, and come back home every day — that’s it.” Living such a circumspect life leads to uninterrupted time for artistic activity, but at tremendous risk. “The center of Damascus is still safe,” he notes. “But in 2013–14 there were bombing events every day. I gambled with this situation.”

Some of the parched and cracked clay Yazigi uses in his work is sourced from earth now being razed by ISIS. Though clay is difficult to locate in Damascus, he has managed to produce scores of simple terra-cotta reliefs. They show people involved in everyday scenes of life, including episodes of lust and desire, strictly taboo subjects for the fundamentalists. His pieces also reference the great terra-cotta reliefs and alabaster sculptures of Mesopotamian and Syrian art, like the ones in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art and other institutions. The ancient cultures that produced those were also militarized and severe; their armies did not just subjugate through battlefield conquest, but raped, beheaded, and flayed corpses publicly. The museum treasures they left behind echo what ISIS has recently destroyed, like the Northwest palace of Ashurnasirpal II in Nimrud (Mosul), as well as other sites currently in danger.

In this context, the focus of the local art scene has shifted from Damascus to a revitalized Beirut, where many of the one million Syrian war exiles in Lebanon have found refuge. Yazigi’s bronze sculptures are cast there in a suburban foundry, and Beirut serves as a conduit to the larger world. It is nonetheless challenging to keep the momentum of art alive, when the Syrian nation is in urgent diaspora. Issues of movement, transportation, and audience make producing painting and sculpture difficult, as opposed to more easily digitized and distributed works like photography and video.

In Damascus, Yazigi has his studio in the old Harat al-Yahoud Jewish Quarter, which until 2015 had a 3,000-year history of Jewish habitation. Elderly occupants can recall the names of former Jewish families, and faint Hebrew letters can still be found among the old signs and buildings. In 1992 the government allowed Jewish families to emigrate. Four thousand of them left, and over 200 structures fell into ruins. In 2008 local officials, taking a cue from many other cities trying to revitalize aging, decrepit districts, turned the area into an artists’ quarter and tourist destination.

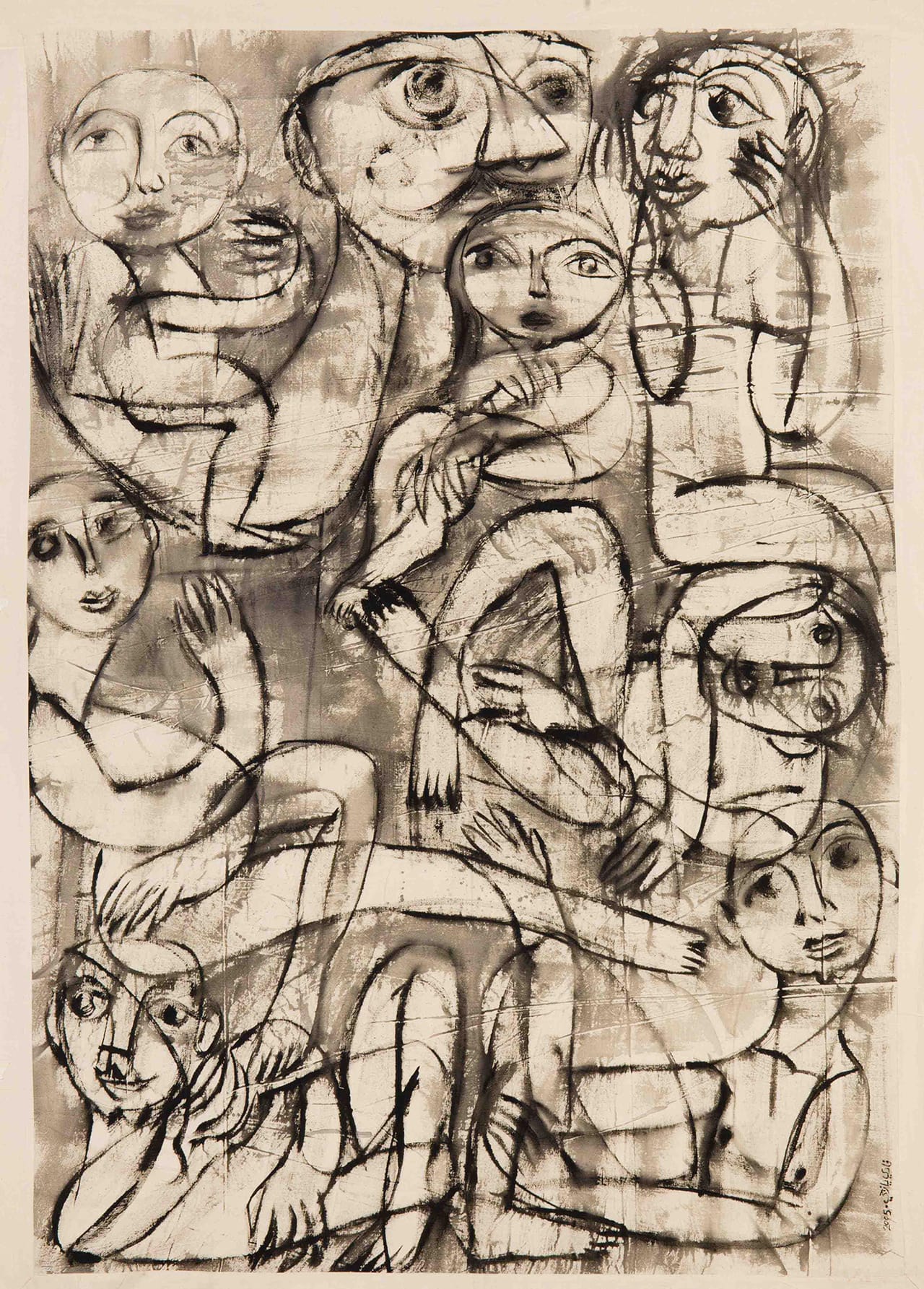

Appropriately, Yazigi’s paintings and sculptures seem to echo the modernism of Marc Chagall and Ben Shahn, as well as shades of Pablo Picasso and Paul Klee. “The faces and figures emerge as if from the windows and doorways of the old Jewish Quarter where Yazigi works,” notes Yallay Gallery. Chagall’s early work is infused with folk culture (“The Fables of La Fontaine”), relationships (“Lovers”), and the Bible (lithographs like “Sara and Abimelech”). Shahn, who migrated with his family to New York, pursued social realism as well as symbolism, striving to mix art and politics without watering down modernism’s expressive message or abstraction’s fluency and immediacy. Yazigi’s work deals with similar issues, but he chooses to follow the stylistic constraints of “effective form” put forth by Adham Ismail, the first Syrian artist to integrate modernism into his oeuvre. It uses anonymous figures, enhanced by repetition, to highlight psychological states of stress.

Yazigi has shown regionally in Beirut, Damascus, Amman, and Bahrein, and Christie’s in Dubai has sold his work. He has been supported over many decades by a dedicated collectorship, mostly from the Middle East and Europe. But this is his first solo show in Hong Kong, where he can reach a much wider audience than before. In 2013, the owner of Yallay Gallery, Jean Marc Decrop, invited six Syrian artists to exhibit in a group show called Syriana; Yazigi was among them. His work kept developing in spite of — and because of — the Syrian war, so much so that Decrop offered him a solo exhibition, which highlights his strengths across three disparate mediums and follows the trajectory of the war and its impact on the lives of those in Damascus.

“We are living in a medieval century, not the 21st century,” says Yazi. “I feel ashamed for this Earth. I insist to use this situation — it is my right, my obligation to do this. What is happening in Syria, maybe we read about these types of things in novels from World War II, but it is happening again now.” His pieces reflect this tension by striking a delicate balance, infusing the tenets of contemporary Syrian art with his own brand of symbolism, metaphor, and the plasticity of brushstrokes. He foregrounds the human figure in order to convey the realities of horrific acts that are deeply experienced, but nevertheless unnamable.

Fadi Yazigi: Contemporary art from Syria continues at Yallay Gallery (Yally building, 6 Yip Fat Street, Unit 3D, Wong Chuck Hang, Hong Kong) through November 28.