An Unintellectual Theory of Tastiness in Art History

No Vanitas paintings, no parables, no metaphors — just pigging out.

I’m of the belief that a well-rounded life demands a bender here and there. I’m not suggesting a dip into hallucinogens, per se — rather, a little break from the superego, a little indulgence in the id. Turn off that big brain of yours, just for a moment. Sit down. Pig out.

With that in mind, I’ve curated a collection of works from art history that I want to eat. I’m putting forth a theory of “tastiness” here that is not intellectual but carnal, not even necessarily seen, but felt. I think the art world could use a little more of that, honestly.

Most of the works depicting food in art history are not, I hazard, tasty. Dutch Vanitas paintings are perhaps the biggest culprit, even though they contain a veritable cornucopia of things that are tasty in real life: succulent fruit, cured meats, fire-hydrant-red lobsters. And I’m not even talking about the paintings depicting meals that have already been picked through by someone else, which, gross. Not a single work in this genre is verified tasty.

Take Jan Davidsz. de Heem’s (uneaten) “Still Life with a Lobster and a Silver Cup” (c.1649–59), for instance. An uncanny cold light washes over the scene like a surveilling spotlight; the scene is so still that it doesn’t feel real. The oysters are fleshy, a slit melon spitting out its seeds is almost gory, and a crab, for god’s sake, locks eyes with you. The scene looks like the last thing you see before you die. Even if you didn’t know about the fucked-up history of how these goods got to this table in the first place (which I’m not going to get into, because we’re smooth-braining here), nor the fact that paintings of this genre are meant to remind you of your impending death, this meal is clearly cursed.

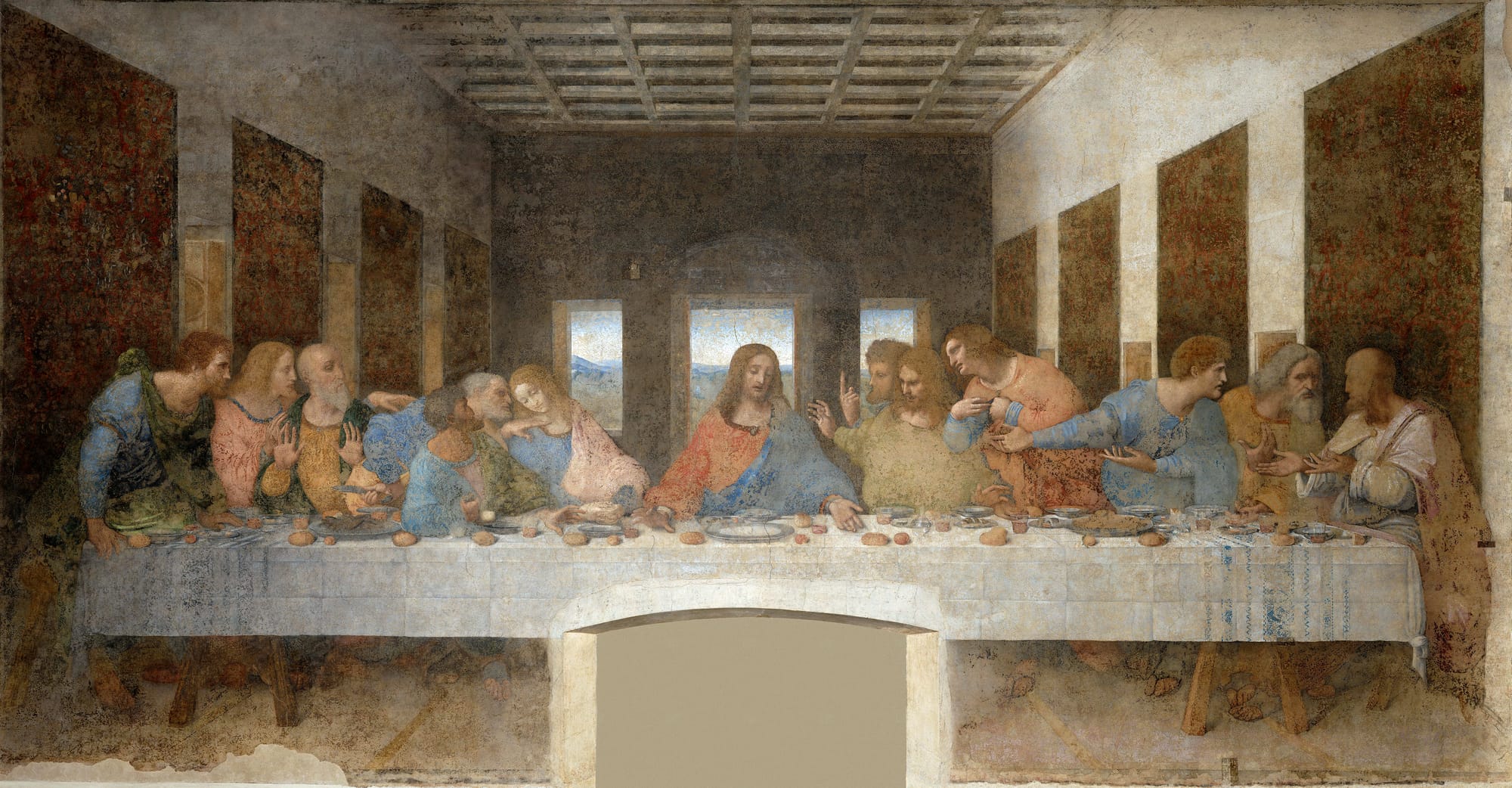

Don’t even get me started on the pathetic picnic basket, not to mention terrible ambiance, of Édouard Manet’s so-called “Luncheon on the Grass” (1863) — no. Or the sad little hunks of bread in Da Vinci’s “The Last Supper” (1495–98). No! Horrible. Not tasty.

Let’s get into the tasty. “Meat-Shaped Stone”: tasty. I mean, just look at it. You know it’s tasty when I don’t even have to explain why it’s tasty. Its top layer is perfectly caramelized. Its striated layer of fat suggests a tender, juicy, bite (I mean, if it weren’t actually a rock). Its presentation, with its cute little golden throne, is fantastic, befitting a Michelin-starred restaurant.

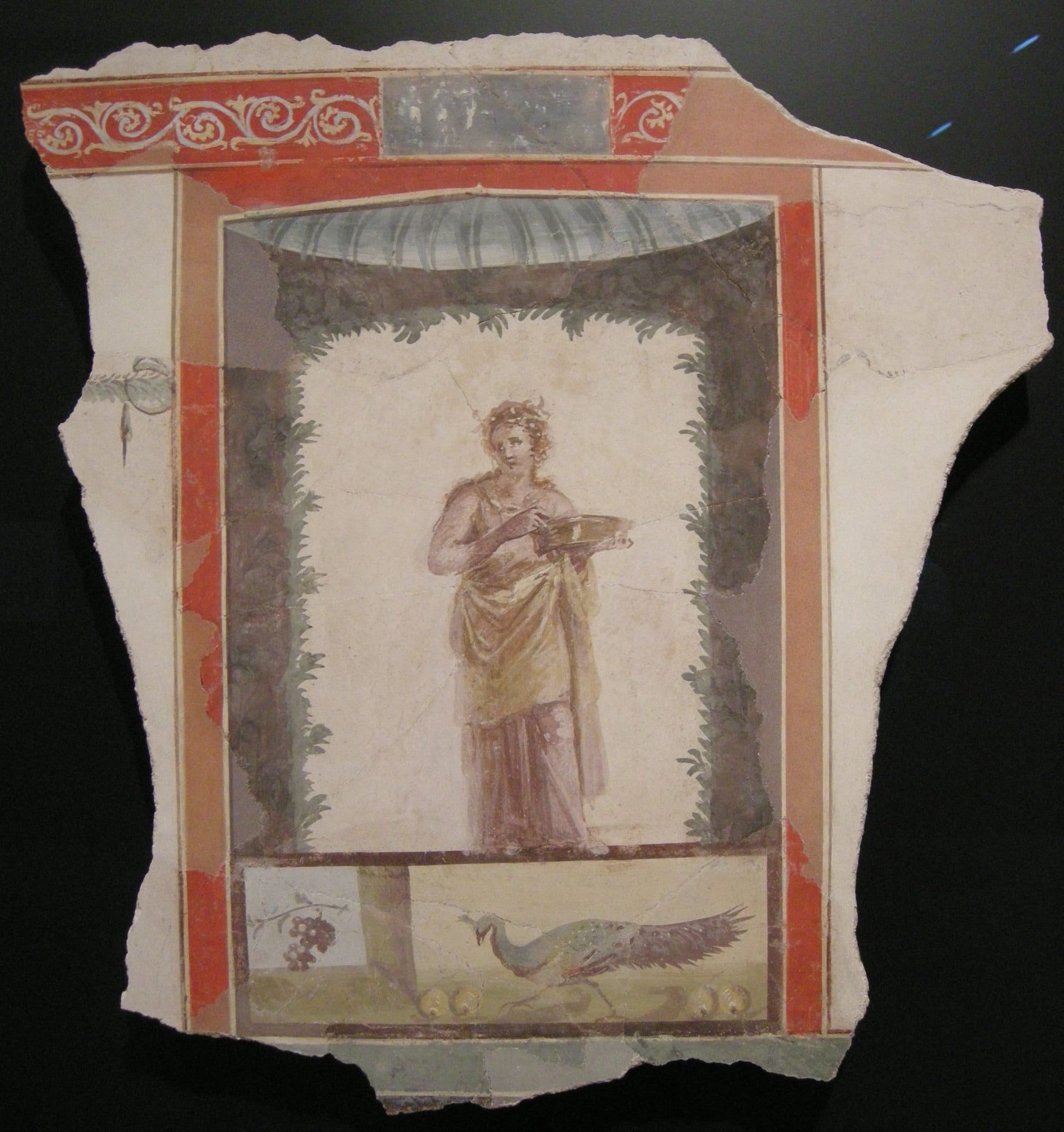

Now that you’re with me, let me start to lose you a bit. The Romans, despite a number of unsavory practices we’re not getting into here, really knew how to live. And some of those frescoes they made are delectable.

Take this one, dated to the first century of the common era. Forget that it might depict a maenad — a follower of Dionysus, god of wine — bringing in food for some unimaginably amazing party. Let the art history fall away, and think upon all the times you’ve seen this scene in real life: a family member, a lover, a friend — someone to break bread with, to share a meal with — at some sun-bleached threshold with a dish for the table. What’s actually on the platter? Doesn’t matter. It’s like the box in Pulp Fiction (1994) — whatever it is, it’s radiant.

Okay, bear with me. We’re about to get even more abstract. I posit that “tasty” is a state of mind. Our Staff Reporter Isa Farfan, for instance — along with some portion of Twitter — wants to eat Moo Deng. That’s what I’m talking about. Obviously, no one’s hunting that succulent little hippo down, but what we should do is expand our sense of what is delectable beyond that which is appropriate, attainable, or even possible.

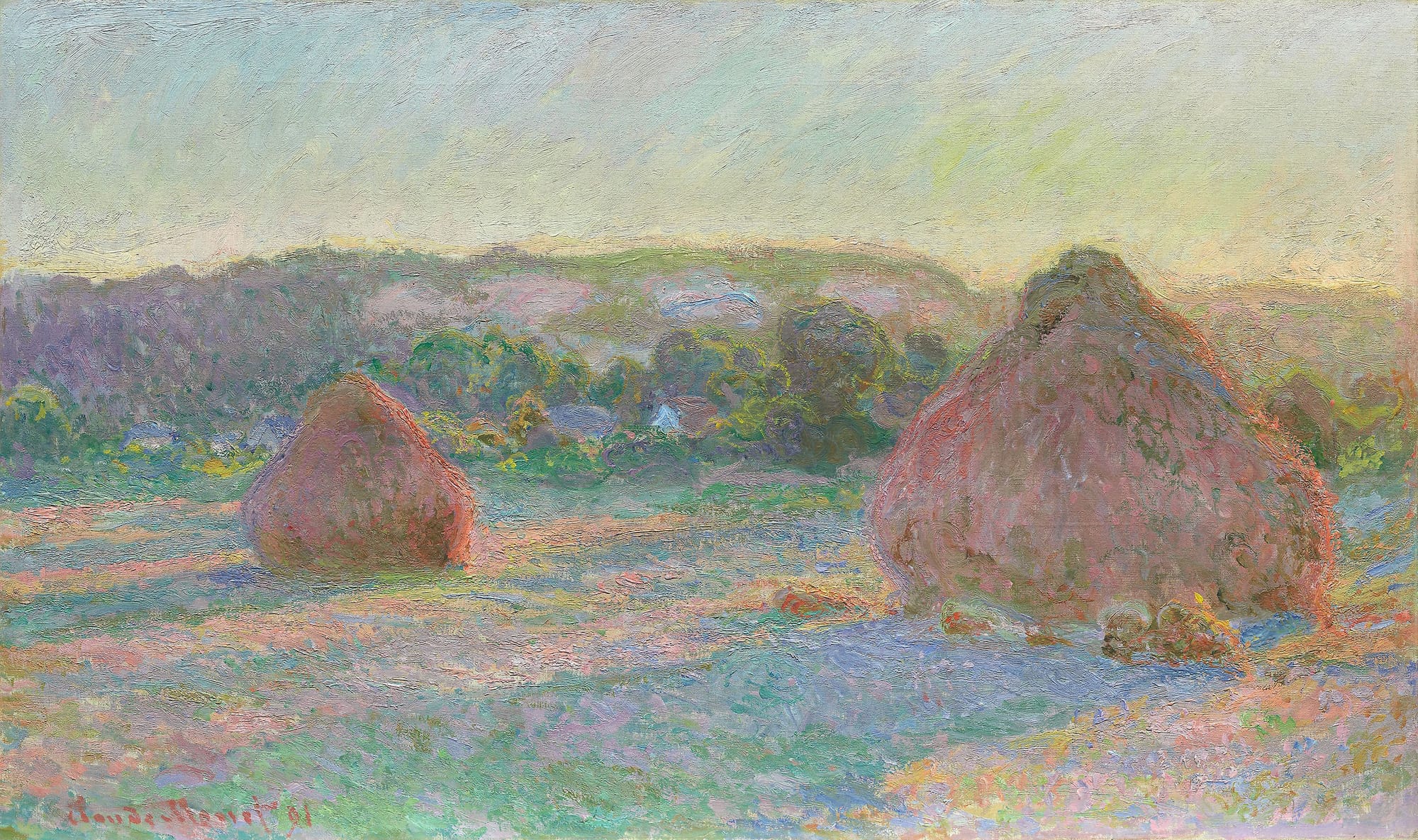

With that in mind, I give you, of all things, haystacks, or really many of the works of the Impressionist movement. It’s not so much that these subjects look like large gumdrops. It’s the candy-colored pastel of Monet’s brushstrokes, which were never meant to capture the thing itself but rather the particular moment of that thing in time. I wish I could put this painting under my tongue, and let it dissolve like one of Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s candies (which, if you’re getting the gist of this philosophy, are actually not tasty, because it reminds you of the tragic death of his lover). Haystacks aren’t tasty, but the feeling induced by this painting of them is. The taste of that late summer light says to me: There’s time yet, but it's going, going — and in the meantime, savor how sweet this life can be.