Art from Solitude

Two words in the English language describe what it means to be alone. "Solitude" results from a willful act of self-reliance, while "loneliness" stems from being involuntarily deprived of company. For most artists, though, the boundaries between these states of being are less sharply defined.

Two words in the English language describe what it means to be alone. “Solitude” results from a willful act of self-reliance, while “loneliness” stems from being involuntarily deprived of company. For most artists, though, the boundaries between these states of being are less sharply defined.

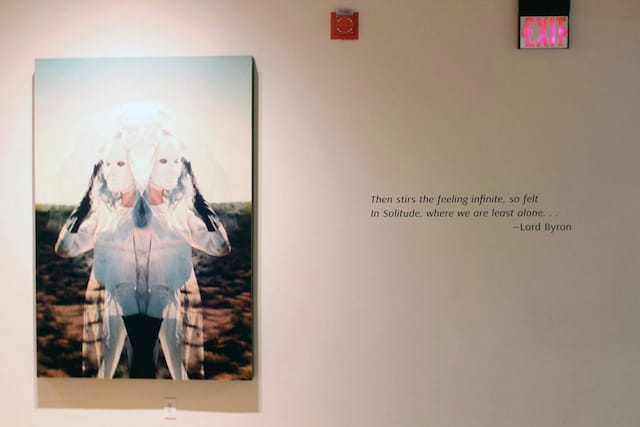

In Solitude, Where We Are Least Alone at ASU Art Museum affirms the impulse toward reflection and self-reliance — critical to any creative endeavor — while also contemplating the thin line that keeps loneliness at bay. As first-time curator Brittany Corrales asks, “At what point does solitude cease to be a refuge from society?”

Corrales takes her cue from American transcendentalists like Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson, who saw seclusion as an act of disconnecting from society in order to better one’s self. “Guard well your spare moments,” Emerson once advised. “They are like uncut diamonds. Discard them and their value will never be known. Improve them and they will become the brightest gems in a useful life.”

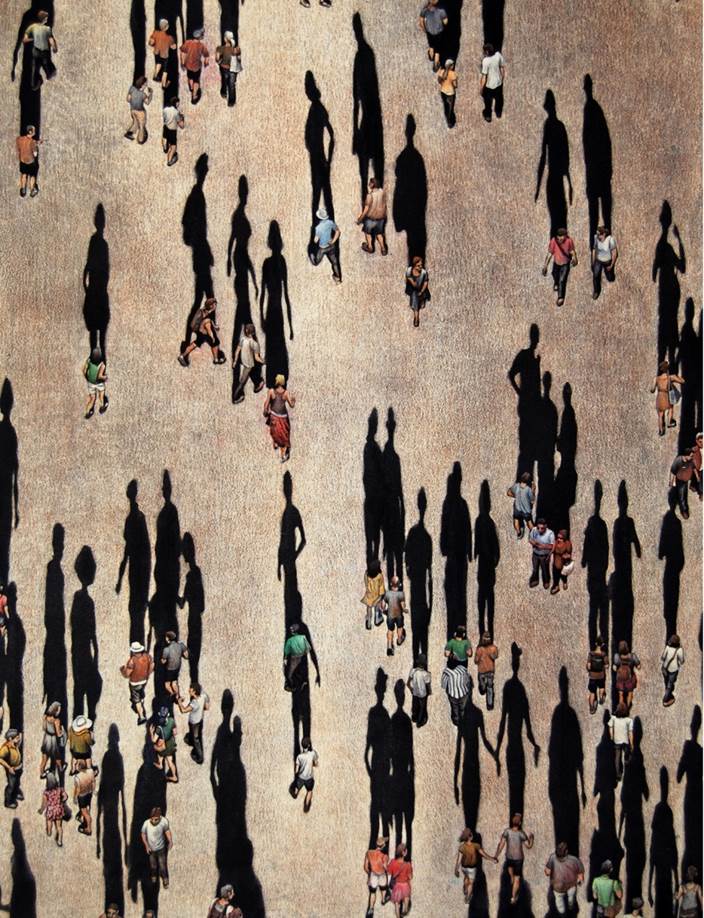

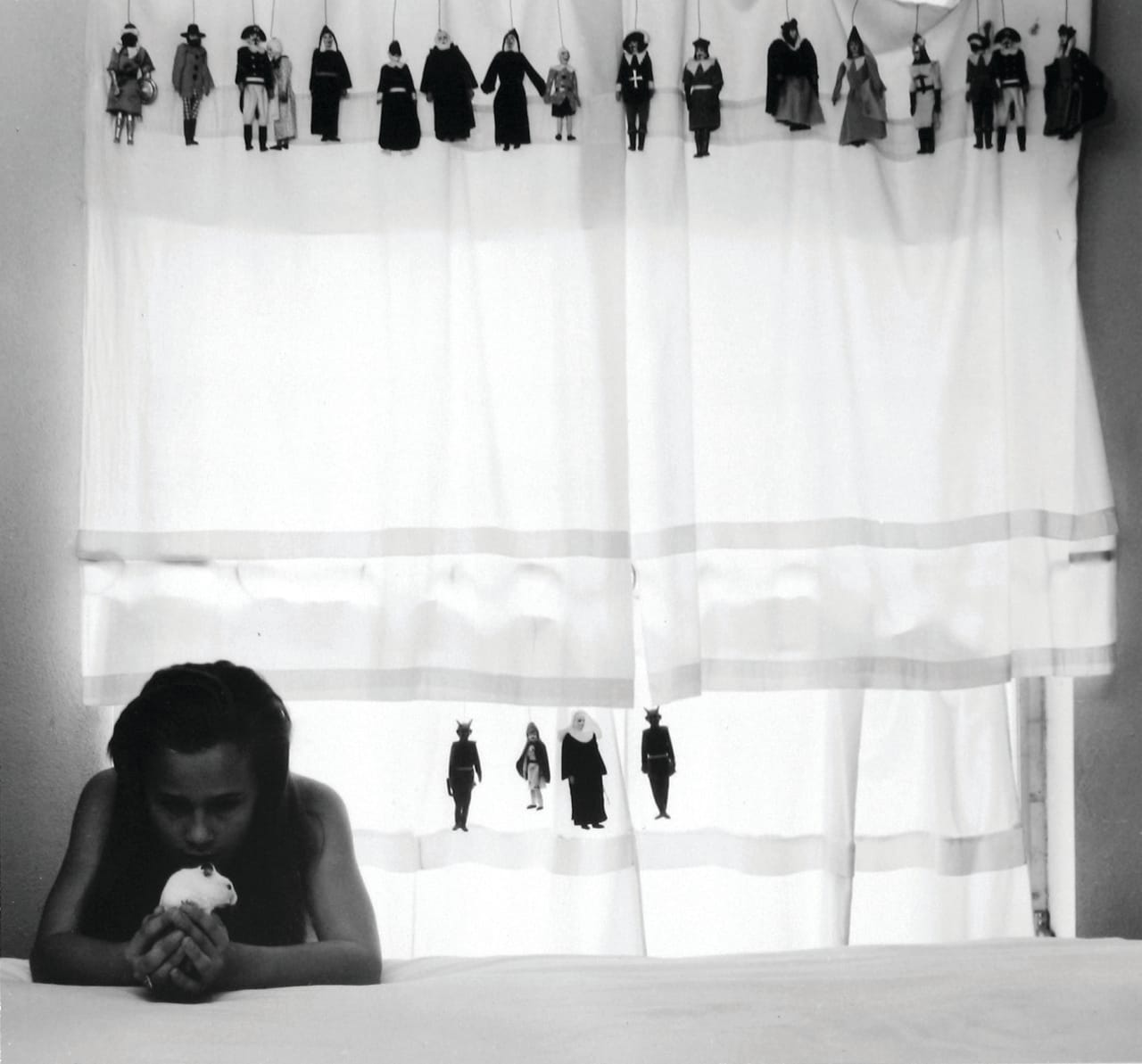

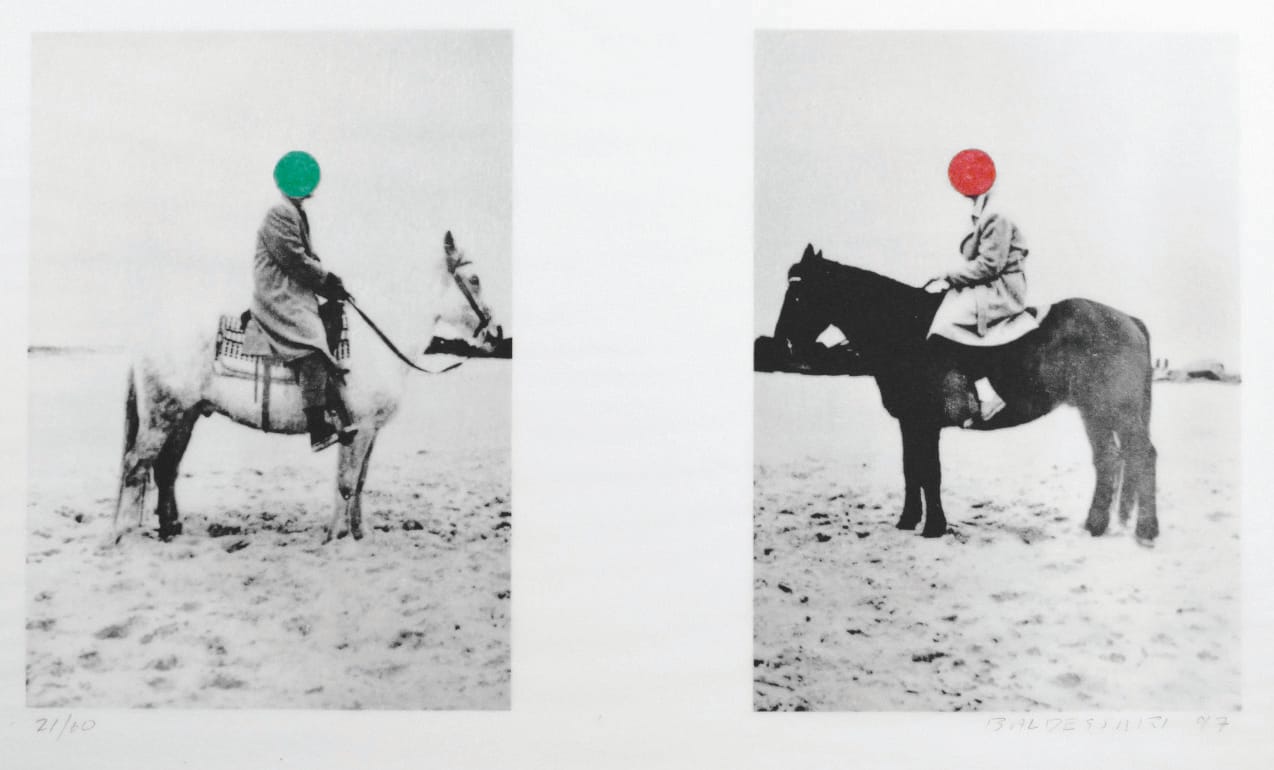

The curator chose artworks that encourage introspection through an intimate, one-on-one connection between the art and viewer (as opposed to the more interactive installation that have become popular). Like the transcendentalists themselves, artists Tamarra Kaida, Mark Klett, Robert Farber and Marcelo Brodsky tap nature as a vehicle for self-reflection. Others (including John Baldessari, Art Werger, Aimée García Marrero, Claudio Bernardi and Van Deren Coke) explore existential themes through the human body itself. Still others, like Esteban Vicente and Matsumi Kanemitsu, use abstraction to stimulate meditation.

The show is timely, considering that distractions offered by social media are increasingly eating away at our ability to enjoy solitude, even if they don’t necessarily make us less lonely. “[When] we’re hyper-connected in that way, we’re not always being mindful,” Corrales told The State Press. “You’re distracted by everything, and it can be really overwhelming. [This exhibition] is meant to cultivate an experience for the visitor that is full, rich, and reflective.”

* * *