Artist Who Embodies Teenage Intellectual Angst Is Getting a MoMA Retrospective

What will this new retrospective at MoMA, which opens September 28 in New York, reveal about the psyche of the Belgian artist who loves the radical juxtaposition?

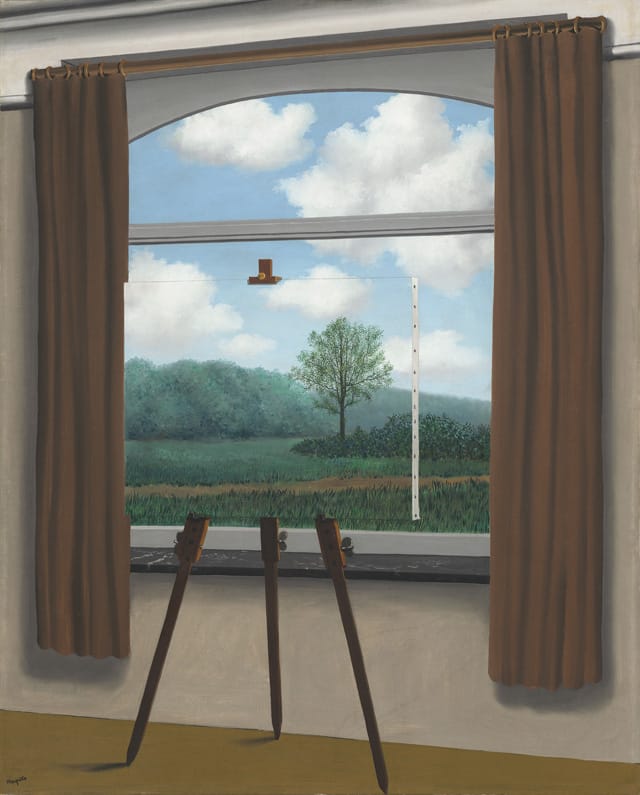

![It doesn't get more ironic than this … René Magritte (Belgium, 1898-1967). La trahison des images (Ceci n’est pas une pipe) (The Treachery of Images [This is Not a Pipe]). 1929. Oil on canvas. 23 3/4 x 31 15/16 x 1 in. (60.33 x 81.12 x 2.54 cm). (Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, California, U.S.A. © Charly Herscovici -– ADAGP – ARS, 2013. Photograph: Digital Image © 2013 Museum Associates/LACMA,Licensed by Art Resource, NY)](https://hyperallergic.com/content/images/hyperallergic-newspack-s3-amazonaws-com/uploads/2013/05/moma_magritte_treacheryofimages-640.jpg)

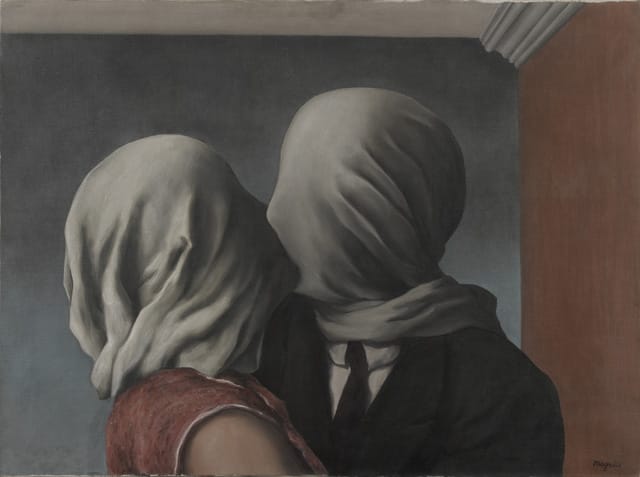

If there was a poll that attempted to plumb the depths of teenage angst and figure out which artist most typifies the intellectual anxiety of youth then my guess is that René Magritte (1898–1967) would place on top (followed closely by Salvador Dalí, of course). And now every teenager in the world (or adults with Magritte-riddled teenage years) will be able to see the originals that inspired these poster-friendly images the world over.

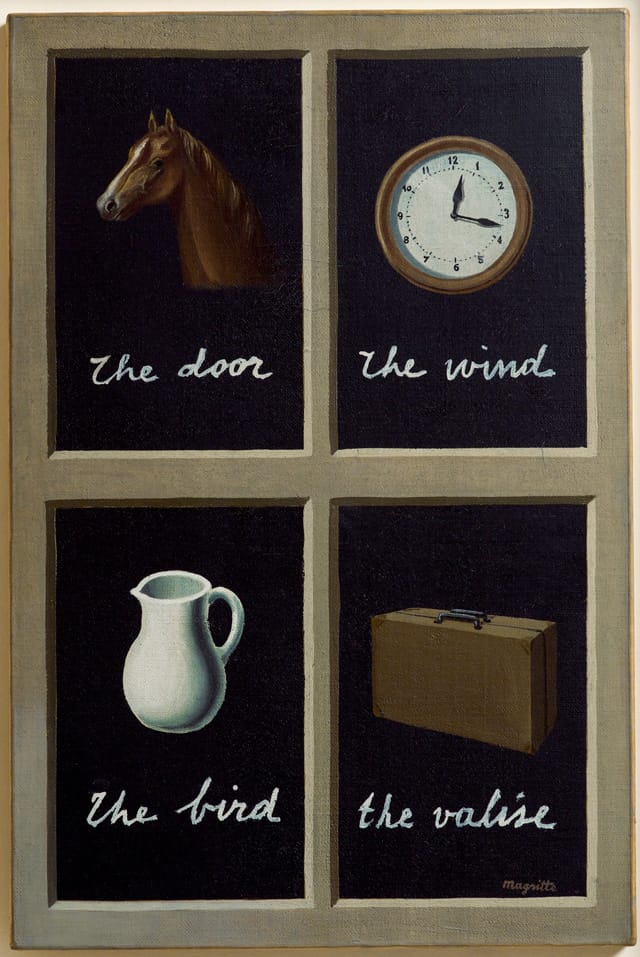

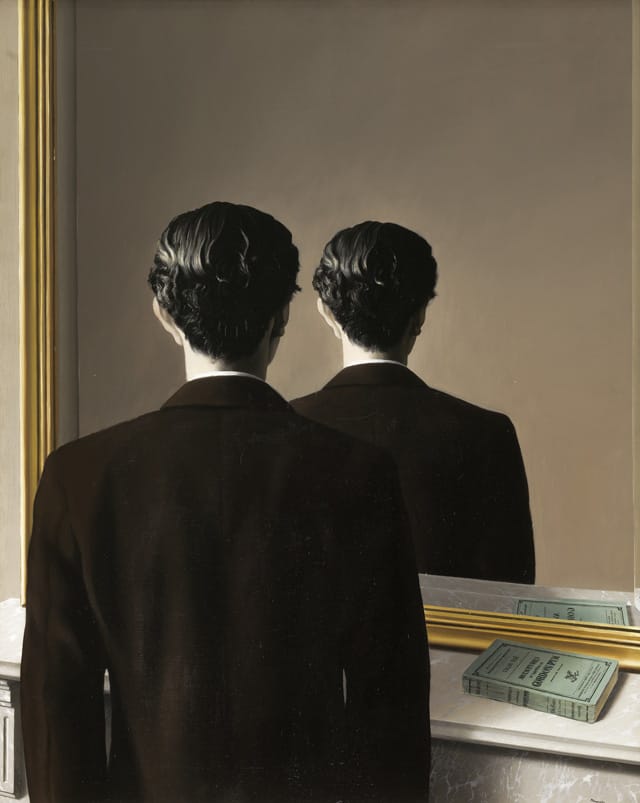

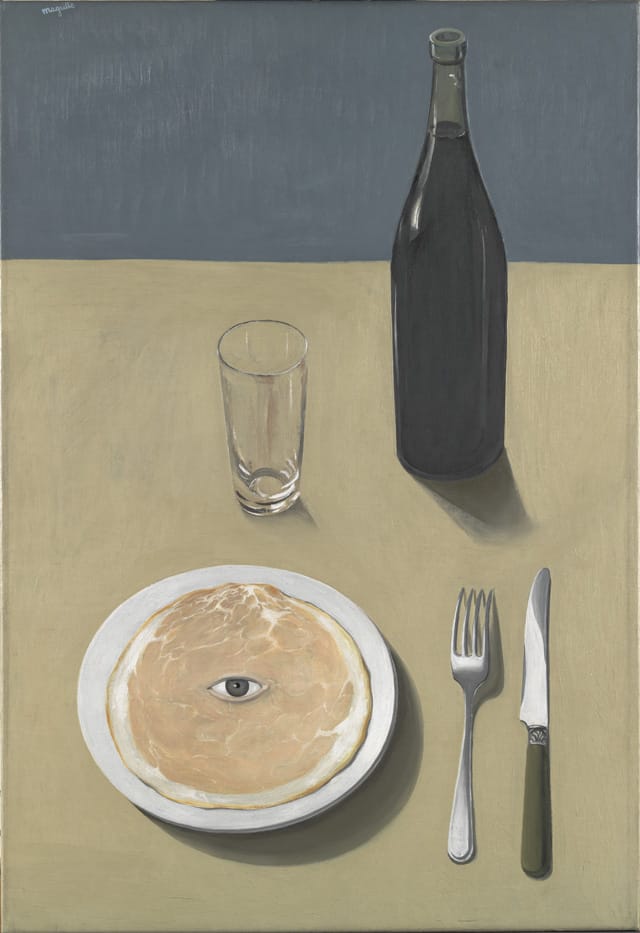

Before the deluge of images we are constantly faced with in our social media- and internet-obsessed world, Magritte was one of the most recognizable soldiers of Surrealism who inspired legions of fans (though most of us grew out of it) through his mis-naming of things — that’s not really a pipe, it’s a painting of a pipe, get it?).

What will this new retrospective at MoMA, which opens September 28 in New York, reveal about the work of the Belgian artist who loves the radical juxtaposition? My guess it will be hard to tell in the crowded galleries as this will be a blockbuster that draws in a record number of visitors.

The retrospective with bring together around 80 paintings, collages, and objects, along with a selection of photographs, periodicals, and early commercial work.

For those who won’t be able to make it to Manhattan for the show, you’ll be happy to know that the exhibition will travel to Houston and Chicago in 2014.

Here’s an interesting (and revealing) quote about Magritte’s childhood:

During my childhood, I liked to play with a little girl in the abandoned old cemetery of a country town … We used to lift up the iron gates and go down into the underground vaults. Once, on regaining the light of day, I noticed an artist painting in an avenue of the cemetery, which was very picturesque with its broken columns of stone and its heaped-up leaves. He had come from the capital; his art seemed to me to be magic, and he himself endowed with powers from above. Unfortunately, I learnt later that painting bears very little direct relation to life, and that every effort to free oneself has always been derided by the public. Millet’s “Angelus” was a scandal in his day, the painter being accused of insulting the peasants by portraying them in such a manner. People wanted to destroy Manet’s “Olympia,” and the critics charged the painter with showing women cut into pieces, because he had depicted only the upper part of the body of a woman standing behind the bar, the lower part being hidden by the bar itself. In Courbet’s day, it was generally agreed that he had very poor taste in so conspicuously displaying his false talent. I also saw that there were endless examples of this nature and that they extended over every area of thought. As regards the artists themselves, most of them gave up their freedom quite lightly, placing their art at the service of someone or something. As a rule, their concerns and their ambitions are those of any old careerist. I thus acquired a total distrust of art and artists, whether they were officially recognized or were endeavouring to become so, and I felt that I had nothing in common with this guild. I had a point of reference which held me elsewhere, namely that magic within art which I had encountered as a child.