Beach House Lullaby

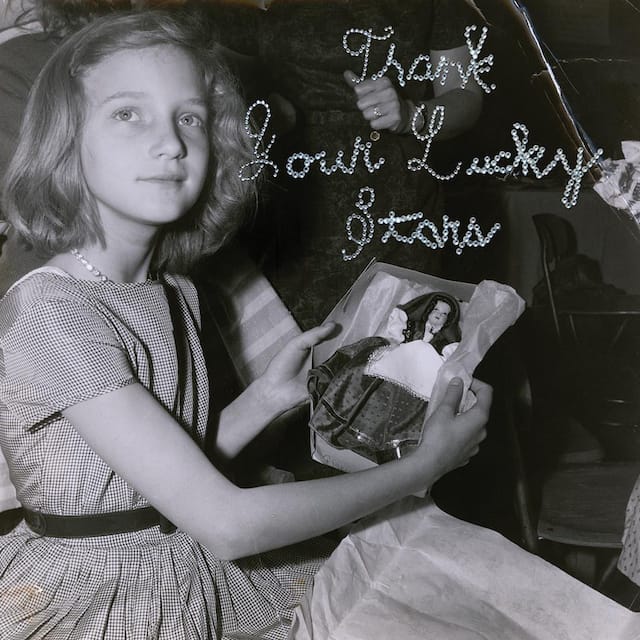

The latest two albums from Beach House, 'Depression Cherry' and 'Thank Your Lucky Stars,' were released this year less than two months apart, and good luck trying to distinguish one from the other.

The latest two albums from Beach House, Depression Cherry and Thank Your Lucky Stars, were released this year less than two months apart, and good luck trying to distinguish one from the other. Maybe Depression Cherry, out since August, sounds a tiny bit brighter and more upbeat than Thank Your Lucky Stars, out since October, with simpler and more cheerful tunes, but only by a differential so minuscule it could easily slip from a casual listener’s grasp. Both albums weave seamless, shimmering dreampop tapestries designed to induce sublimely relaxed euphoria; both albums glow with a sugary surface, warm rays of guitar sunshine, molten atmospheric synthesizer; both albums aim for a snug, contented quality via music that’s much slower, dimmer, and more impressionistic than the group’s previous work, that makes itself felt as a single, irrepressible, textural seep. They sound exactly the same on purpose, one could say.

Where most bands classified as dream-pop bespeak a youthful lyricism notable both for its tenderness and its eternal adolescence, Beach House treat their chosen genre tag more literally: they sound tired, somnolent, as if floating through space in a semiconscious state. Their endless stream of thick, layered, simultaneously clean and blurry guitar sound creates a fuzzy, buzzing, weirdly polished haze — more so on the two new records than on 2012’s Bloom or 2010’s Teen Dream, both of which included lighter, faster, more traditionally shaped melodic pop songs within the same general style, yet nevertheless succumbed to a rich, beguiling passivity. The band’s simple, repetitive, broad tunes; steady, straightforward beats; layers of droneguitar on dronesynth on dronebass on sticky dronesurface on liquid dronecenter; and Victoria Legrand’s smoky voice, which cuts through the music like a laser through rhythmically throbbing fog, have turned them into celebrated indie heroes in an era when most bands working in the same style lack the requisite formal imagination and sonic range to construct a self-sustaining musical environment. Bloom and Teen Dream garnered wide critical acclaim from publications like Spin, PopMatters, Consequence of Sound, etc, finishing 7th and 10th in the Village Voice’s year-end Pazz & Jop Critics Poll, respectively. While Depression Cherry and Thank Your Lucky Stars may very well achieve the same, I bet the consensus rates them lower, because they’re nowhere near as catchy. The two albums turn the band’s lavish approach altogether more abstract, more minimalist, harder to focus on, harder to internalize. This is music so slow, so sumptuous, so mesmerizing it all but evaporates when you play it, though it might also conquer the indie world through vibes alone.

From their jangly-fuzzy veneer to their stunned-languorous flow, Beach House position themselves firmly in an honorable indie-rock tradition with roots in the late ‘80s, when select bands (Jesus and Mary Chain the first, probably, but not the last) ditched and/or took to its logical conclusion the punkoid crunchaguitar template by relentlessly pursuing atmospheric drift, in the process inventing such celebrated genres as shoegaze, ambient noise-rock, and dream-pop (just how different are these three? only a true shoegazer could tell you). Those bands were inventing something weird and genuinely original, a conscious, measured response to formal stasis in the surrounding indie world and/or adult empowerment ideology in the larger pop sphere, conjuring up images of an artier and dirtier underground than actually existed, images of teenagers playing dress-up as five-year-olds retreating into the dark recesses of their latent id and never coming out again, images of an escapist paradise previously unknown to man or woman. Legrand and guitarist Alex Scally are merely exemplary formalists respecting their elders, as hundreds of indie bands have trodden this territory before; alienation effects have become comfort effects. A cross between the Cocteau Twins, the late-’80s and early-’90s Scottish pseudogothic etherealists to whom they are often compared, and Coldplay, whose kitschy, affectless, whoosy-dreamy ambient pop confections are currently topping the charts and getting ignored by loyal Alternativians worldwide, Beach House write real songs — tight, tuneful constructions with comprehensible if somewhat vague lyrics that make sense when read on the page — but Legrand and Scally so overwhelm those songs with grand, sweeping washes of guitar sound that the dazed, sunbaked feel comes first, the melodies second; they aim to induce in the listener a luxurious, childlike elation more amenable to full, mindless immersion in the music than to any reasoned response. Thus do they construct something like a safe haven for sensitive, emotional young people — a sensual respite where one can simultaneously hide from and wallow in one’s own adolescence — much the way both the Cocteau Twins and Coldplay do, albeit for different audiences with different tolerances for schlock, much the way the early shoegaze bands did, much the way increasingly insular indie bands have been doing for decades now. Any troubled teenager frustrated with the cold, unfeeling outside world can take shelter in Depression Cherry or Thank Your Lucky Stars and find for themselves a warm, tangible blissworld.

Legrand and Scally have insisted that Depression Cherry and Thank Your Lucky Stars aren’t related projects in any way, that they just happened to be unusually prolific this year, which must be their way of telling us not to play the two albums back to back lest we accidentally hypnotize ourselves. Indeed, each record works as its own independent entity — Depression Cherry got rave reviews before the release of Thank Your Lucky Stars was even announced — and there are, in fact, differences to be discerned. Legrand’s vocals are slightly breathier on Thank Your Lucky Stars, slightly throatier on Depression Cherry. Depression Cherry depends more on hooks, Thank Your Lucky Stars on glide. Thank Your Lucky Stars includes more ominous tunes, Depression Cherry more cheerful ones. Depression Cherry’s songs are easier to remember thanks to the cascading, circular guitar riff on “Ppp” and the hushed jangle on “Bluebird” and the mellow distortion on “Sparks,” although Thank Your Lucky Stars certainly shines during the airborne “Elegy to the Void” (what a title) and the glistening, synthetic organ vehicle, “The Traveller.” But these are minor distinctions, and anyway, comparison feels wrong given the band’s artistic end. Both albums open different doors of perception to the same peaceful, enchanted dreamland, where passersby can marvel at soaring, helium-coated guitar sculptures over their heads, feel the reassuring pulse of bass patterns beneath their feet, and curl up in a cozy blanket of sweet, staticky electronic sound. The band’s strategy on both albums is to write increasingly simpler and more repetitive songs while slowing down the tempos and allowing for long instrumental breaks during which they pile on the balmy distortion effects, to make the music more pure, more abstract, therefore capturing more truly that special escapist place on record. Compared to their last two albums, both of which included distinct verses, choruses, and the like, these more formless compositions gradually mesmerize over extended periods of time. At times they recall contemporary (you know, 20th-century) classical minimalism, only where classical minimalists repeat melodic tropes over and over again while every now and then changing something ever so slightly, so that the music shifts and jumps intriguingly in complex, multifaceted shapes, these songs contain no inherent shift; they drag on into eternity unchanged, stacking big, vibrating blocks of sound higher and higher, with no entry point. This has an effect opposite to what’s intended, diluting rather than enhancing one’s view of the imagined aural world, dulling the musical charms of what was already a specialized taste. The end result is an aural world that’s a little too soft, a little too cuddly, a little too infantile.

Depression Cherry and Thank Your Lucky Stars will achieve modestly impressive sales, win solid critical acclaim (Depression Cherry more than Thank Your Lucky Stars, I’d guess, although you could make an equally valid prediction with a coin flip), and provide thousands of vulnerable young people with inviting, blissful escape. Afterwards, both albums will vanish into the ether, slowly melting away into the atmosphere. Fans will notice and moan in denial, reaching out to grasp those tunes they thought they once heard, only to find nothing between their fingers once the texture clears.

Thank Your Lucky Stars (2015) and Depression Cherry (2015) are available from Amazon and other online retailers.