Beer With a Painter: Mary Lovelace O'Neal

“At this marvelous hard-won age, the days of jumping and dancing with the paintings are over. But I don't feel limited,” says the artist, educator, and Civil Rights luminary.

“I can mark” is a phrase Mary Lovelace O’Neal uses often. Rightly so: She has been leaving her mark since the late 1960s, both on painting and on the Civil Rights movement, particularly as a founding member of the student-led Nonviolent Action Group at Howard University, where she studied with luminary artists including David Driskel. She counted Malcolm X, Martin Luther King Jr., and Fannie Lou Hamer among her mentors in the movement.

The artist splits her time between Oakland, California, and Mérida, Mexico, where she was staying when we spoke over the phone in December. We connected over the fact that I had recently visited Jackson, Mississippi, her birthplace. There, she tells me, she was treated as a third-class citizen by segregated institutions, including the zoo, library, and art museums — where Black people were only allowed to visit on select days of the month.

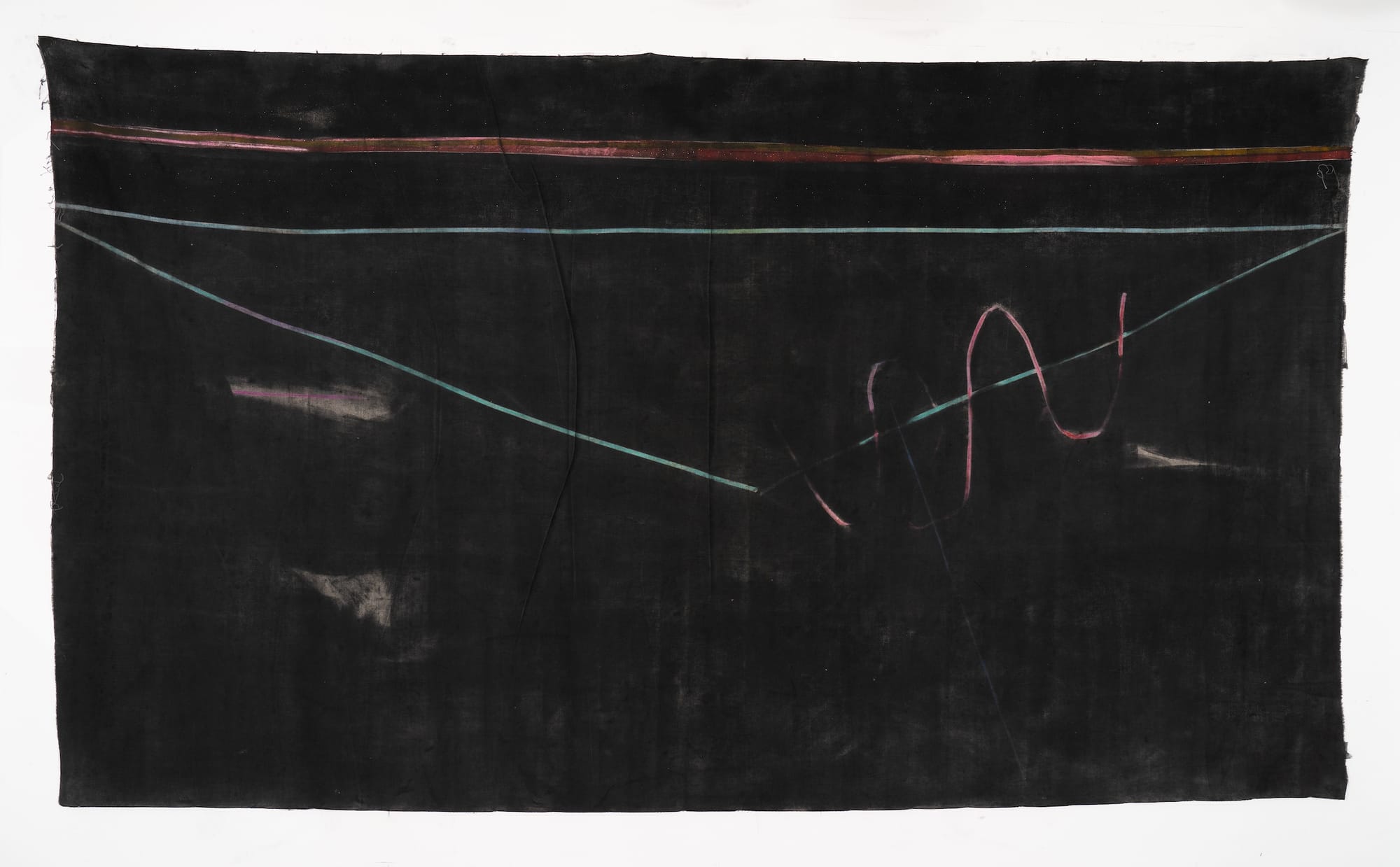

Lovelace O'Neal's paintings are rife with big marks and energetic movement, acting as declarations of presence in spaces where she wasn’t welcome. In her early Lampblack series (late 1960s), she encased the fibers of her canvas with the titular powdered black pigment before moving across the entire surface with linear color. Her Whales Fucking series (1979–early ’80s), on the other hand, considers the water displacement made by the aquatic mammals. Other work homes in on the subtle ways women subvert rules and move through repressive societies. She balances abstraction and recognizable motifs, layering elements with emotional density: beauty and pain dancing together.

Born in 1942, Lovelace O’Neal earned a BFA from Howard University in 1964 and an MFA from Columbia University in 1969. Her work has been the subject of solo exhibitions at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the Cité International des Arts in Paris, and the Mississippi Museum of Art in Jackson. She is professor emeritus at the University of California, Berkeley, and will be the subject of a solo exhibition at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts this year. This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Hyperallergic: You grew up in Mississippi and Arkansas, and traveled each summer to the Midwest by train. Can you tell me about your early experiences with artmaking?

Mary Lovelace O’Neal: I was born in Jackson, Mississippi, where my father was a young professor at Jackson State College. But I did most of my growing up in Pine Bluff, Arkansas, after he became chair of the Art Department at what is now the University of Arkansas. Our family traveled by train every summer to Chicago. Daddy wasn’t trying to make us into artists, but he gave us crayons, scissors, and glue to keep us from acting out on the train. We could get crazy easily; the three of us grew up like weeds on college campuses.

At first, we stayed in our train compartment so that we did not have contact with the ugliness of train travel in the South. Immediately after we crossed the Mason-Dixon line, the trains were not segregated, and we were able to go to the dining room. There were gorgeous Black men in their serving clothes, and beautiful silverware, glassware, and white tablecloths. I felt like a lady.

When I was in 11th grade, we moved back to Jackson when my father became chair of the Music Department at Tougaloo College. I studied with professors who were European exiles during the Second World War. Many of them ended up teaching in Black colleges and universities.

One of them was Professor Ronald Schnell. He, along with Dore Ashton, developed a modern art collection at Tougaloo. I was supposed to be learning German, but Professor Schnell said to Daddy, “Why don’t you let Mary take the art class? Her papers are full of doodles where she is supposed to conjugate verbs.” When I was 19, he arranged for me and Harold S. Dorsey to do a mural at a juke joint.

H: As an undergraduate student at Howard University, you studied with James A. Porter, David Driskell, Lois Mailou Jones, and James Lesesne Wells. You were also active in the Civil Rights movement. Can you tell me about this time?

MLO: The March on Washington was in 1963, and my boyfriend at Howard was Stokely Carmichael. Our friends came up, and that same summer there was a solar eclipse. It was an incredible period of time — scalding. So many people who were important in my development are gone, along with Malcolm [X], Martin [Luther King Jr.], Medgar [Evans], and Fannie [Lou Hamer].

In the summer of 1963, I went to Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in Maine because Mr. Driskell encouraged it. Ms. Jones didn’t think they should send me. She said I would cause some kind of ruckus and have a picket line out in front. She said, “Have you seen that trench coach and those sneakers? Look at her hair!” I wore my hair natural. But Mr. Driskell insisted.

Skowhegan was where so much started to change. A visiting sculptor gave a demonstration. He was working on an armature and had a big pot of lamp black pigment brewing. I was fascinated by that pot and what he had done with it, so I stuck around after the presentation. I asked if he was going to use the rest of the black pigment, and if not, if I could have it. I knew I needed it. He agreed, and then essentially asked me what a Black woman was doing there.

H: Can you share more about your time at Columbia University, and how your early black pigment paintings developed?

MLO: Between 1963 and 1969, when I graduated from Columbia, I married John O’Neal and went to jail a couple of times. I was extremely thrilled by the beautiful political artwork that Chilean, Mexican, and South American printmakers were making, but I couldn’t do that. All I could do was put my body on the line.

My then-husband, John, was a playwright and cultural activist. The poets of the Black Arts movement, like Amiri Baraka, came to our house a lot. They criticized my work for not having the social and political narrative they expected from a Black artist.

I also had trouble with my professor Stephen Greene. I was making gestural work, and Stephen’s attitude was, “Nope. Not gonna work.” The new guys were the minimalists and the Color Field painters. Frank Stella had been one of Greene’s students, which was his claim to fame. Greene was challenging everything I was doing, and it was clear that I had to accommodate what he was talking about; I hid what it was I wanted to talk about.

One day, I went to Pearl Paint. As I walked down one aisle, I noticed a black pyramid developing on the floor. It was dark and velvety, so I got closer. There was a tiny hole in a paper bag, and pigment was slowly pouring out. I continued shopping, but kept ending up in that aisle. It reminded me of my Skowhegan experience, so I bought four bags.

The pigment sat on a shelf in my Columbia studio for weeks. In the meantime, my husband had prepared some big canvases. I kept looking at the pigment, and at those intimidating, blank, white canvases. Eventually, I realized I could do the slashing and dripping and cover it up with black. I could go back in and pull up bits of color. One day, I poured a bag of the black powdered pigment into a bowl. I finally had the nerve to go all the way through the canvas.

I thought to myself: It can't get any flatter and more minimal than this. I am encasing fibers with black pigment. And it'll be hard to find a black that’s blacker than this. So in my imagination, I had satisfied both arguments — the formal and the political.

I got out of Columbia just as the riots and the capture of the school started taking place. I wasn’t ready to go to jail with the undergrads. The activists were with the real heroes; I see myself as a resistor.

H: In the 1970s, you lived in the Bay Area and taught at the School of the Art Institute (SFAI) before joining the faculty at the University of California, Berkeley, until retirement in 2007. It was there that you began your Whales Fucking series. Tell us about that period in your work.

MLO: In the 1970s, I was an itinerant, teaching anywhere I could. I taught at SFAI, and eventually had to sue the school because of the way they were dismissing African-American women. Jay DeFeo was there at the time, and we used to smoke and drink and paint together.

One of my first students was Violet Fields, who I loved. One day, we went out in my ragtop VW to a city beach. That's where I saw a whale for the first time. I was walking down the beach bitching about how horrible the SFAI was, and the sprays of water caught my eye. The whales were migrating north for the summer. It was a fantastic encounter. I started to wonder what huge amounts of water would explode in the air when they were fucking. I couldn't get that out of my head. But I didn't start to work on my series, Whales Fucking, immediately. It took months for me to understand.

H: How did you meet Robert Blackburn, the Black artist and master printmaker? What role did he play in your work?

MLO: I met Bob Blackburn when I came to New York for my show at Kenkeleba House, Joe Overstreet and Corrine Jennings’s exhibition space in the East Village. He invited me to his print workshop. I was resistant, having had horrendous experiences in James Lesesne Wells’s class at Howard, but I went to Blackburn’s place. The minute I hit the door, the smells felt like magic. I was given a stack of paper, but didn’t know what to do. Then I remembered what Mr. Driskell had always said to us: “One of these mornings you're gonna wake up and not have a single thing in your head to paint. That day will surely come. And when it does, my suggestion is to go back to the still life or the figure.” So, I made a still life with oranges. I couldn't believe what came through that big wheel. From that moment on, I was in love with printmaking.

H: At Bob’s invitation, you visited Morocco for the first time in 1984, leading to your Panthers In My Father’s Palace series. What were some of the inspirations for this body of work?

MLO: Bob invited me to his workshop in Asilah, Morocco. I met my second husband, [Patricio Moreno] Toro, around that time, and he told me they would put me in jail. He said, “You're gonna go over there and wear shorts and drink whiskey, and they don't like that.”

We did all that, and would be crawling into bed as the call for prayer came in the morning. The print studio was small, so I started working on the roof of the palace where we lived. From there, I had a view of the women’s activities, which also took place on rooftops: cutting, dyeing, and braiding hair; dinner preparations; salting meat; sewing; bathing children.

The palace had mosaics on the walls, and from my bed, I could see the ocean in moonlight. The setting took me back to being 11 years old, when my father directed a Christmas choir performance at Pine Bluff of the Gian Carlo Menotti opera Amahl and the Night Visitors. They needed dancers, and my father insisted I take part. I knew all the words. Amahl is interested in the Black King, and asks where he lives. The king says, “I live in the black marble palace with black panthers and white doves.” I realized it was a place like Morocco.

H: How did your other travels with Toro influence your painting?

I returned to Morocco because I was interested in making work about women and their dress. I also wanted to go to Egypt, and Toro took me to his country, Chile. After that, I started a series called Two Deserts, Three Winters. The Atacama Desert in Chile is a rocky, hard, male-feeling place. The Sahara is totally different: sensuous, with rolling hills and mounds of soft sand.

I watched the way people moved through the desert. Women seemed to appear with trays of magically colored fresh vegetables. They would disappear through alleyways — a black poof against the white. One day I watched a woman walking up a mountain, all in black, but I kept seeing something green. She was wearing green jelly shoes. There were always signs of subversion.

So much opened up for me, but I had to be careful. The stories started to overtake the painting. I had my head and my heart, but also my tools. My prints functioned as memories. I knew that painting is painting, and my job was to make something from it.

Now, at this marvelous hard-won age, the days of jumping and dancing with the paintings are over. But I don't feel limited. I am always presented with the same problem: how to make what I'm thinking about happen. The marks are hard to come by, but they always were. Often, the material will come to you. You look around the studio and think, Maybe I can use that. I'm open to it. I'm open to listening and hearing and smelling. Things don't just happen. They happen just.