Beer With a Painter: Melissa Joseph

Our series on painters and their practices is back, this time for an interview with the New York-based artist who creates “paintings in felt” to explore her Irish and Indian family history.

When Melissa Joseph welcomed me warmly into her Midtown studio this fall, she immediately invited me to try needle felting — the process she uses to create what she calls her “paintings in felt.” Feeling self-conscious, I procrastinated as long as possible, asking questions in the meantime. But Joseph insisted it’s the only way to understand the medium, so after my final question, she cut me a small rectangle of carpet padding, handed me the needle tool, and invited me to pull pieces of brilliantly colored wool from her cabinet. As I stabbed the wool into place, I suddenly got it. It is meditative, and also a bit violent, which feels healing, alongside the tactile fuzziness of the soft wool.

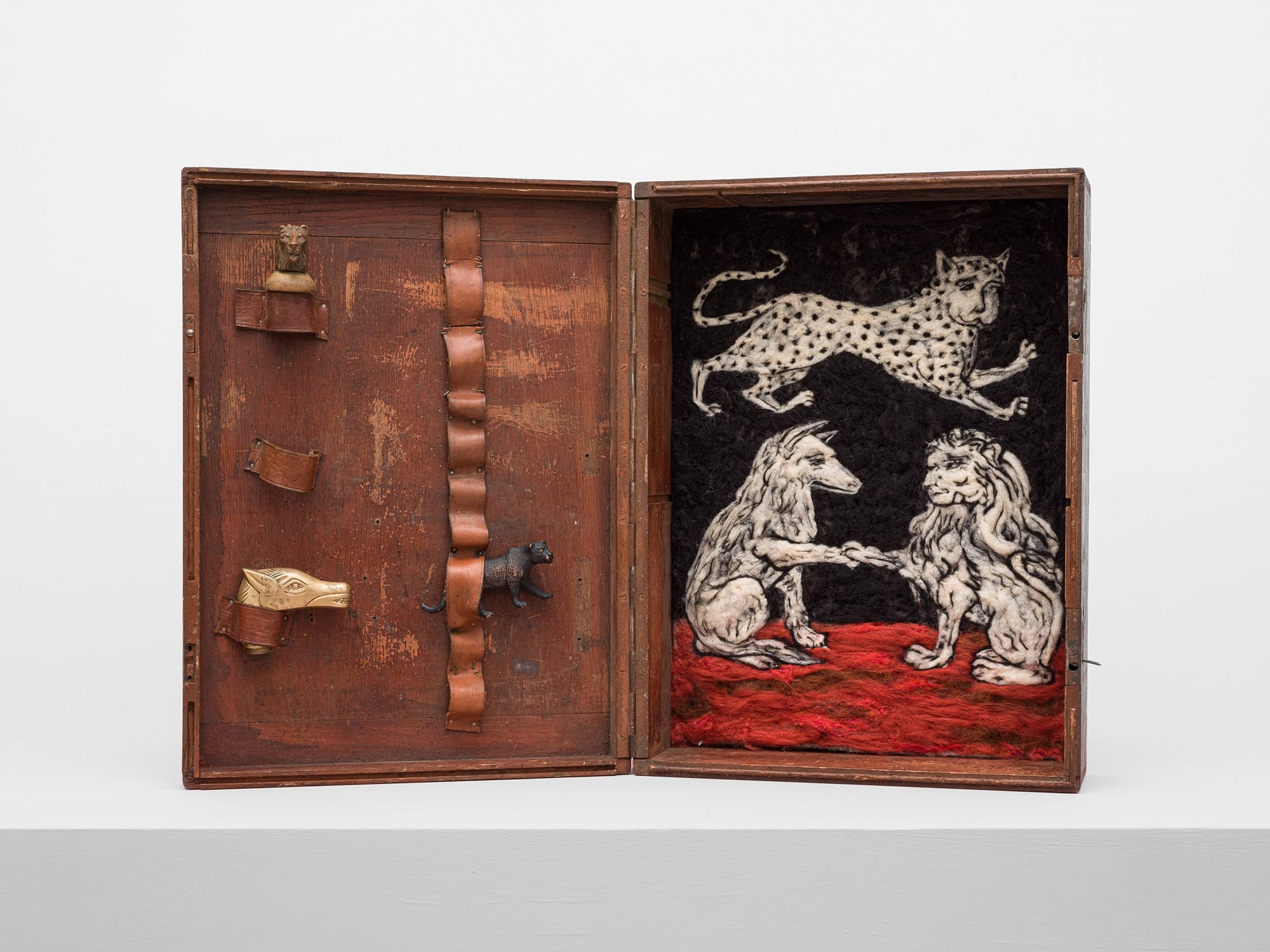

Joseph’s felted works are often enclosed and framed by small containers — found objects like a vintage first aid box, an anchor, or a silver platter. In this way, the memories of family and friends she renders in felt are held like devotional objects or religious icons. Joseph depicts her biracial family with roots in both India and Ireland. Grief and loss were a catalyst for her work; her career as an artist began after the death of her father in 2015. Joseph brings care to candid, sometimes awkward familial moments, simultaneously attaching new meaning to the discarded objects she so tenderly repurposes.

Born in Saint Marys, Pennsylvania, in 1980, Melissa Joseph lives and works in New York City. Prior to receiving her MFA from the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in 2018, she had trained and worked as a textile designer and high school art teacher. Her work has been shown at the Brooklyn Museum, Delaware Contemporary, Utah Museum of Contemporary Art, MOCA Arlington, ICA San Francisco, and List Gallery at Swarthmore College, among other institutions and galleries. She is the recipient of the 2025 UOVO Prize by the Brooklyn Museum and the 2025 Eden Art Foundation Artists Now Award, and is a regular contributor to BOMB Magazine.

Jennifer Samet: Can you tell me about where you grew up, and if you were exposed to art, or made art yourself?

Melissa Joseph: I grew up in rural, pre-internet Pennsylvania. We didn't have fine art around, but my mother was a “picture lady.” A couple times a year, she would come to my school with reproductions of work by Mary Cassatt, Salvador Dalí, or Grandma Moses, and do a presentation in the classroom.

I grew up surrounded by people making things. It was what I call a “casserole culture,” and a hunting culture. Families had deer hanging in their garage and they prepared the meat and made jerky. The women canned fruit and made jam. The adults would send us kids into the woods with garbage bags to collect ground pine. We came back when our bags were full, and used it to make garlands. There weren't a lot of restaurants, so when someone hosted a party, they made the cake; they made the decorations. I took sewing class, fly tying, and hunter safety.

My grandmother was an avid knitter and crocheter, and my mother was a cross stitcher. My mom taught me to cross stitch and I hated the patterns, so she would give me gridded paper to draw my own picture on. In warmer weather we were outside playing, but the other half of the year I was inside playing instruments, learning to paint from Bob Ross, and hot gluing stuff in the basement. Growing up in a steel town explains my connection to wood and stone and rust and steel. These are things that you don't pay attention to, but they silently form your understanding and aesthetics.

JS: You’ve spoken about how you went to graduate school “late,” having already had careers in textile design and teaching. What led you to the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts and what was your experience there?

MJ: I am glad that I went to PAFA and started off in Philadelphia, which has a smaller and more open art world. Didier William, who was chair of the MFA program at the time, is the reason I'm here. I was so lucky, because I had no understanding of what an MFA program was about. I just wanted to study somewhere and to be close to my family since my dad had just died. But Didier was a truly excellent teacher and leader. He basically had a ragtag group of students and he made us into artists — like that movie The Dream Team.

JS: How did you discover felting?

MJ: In 2020, I came to New York to do a residency at the Textile Art Center (TAC) in Gowanus. They taught us weaving, knitting, and screen-printing. One day I saw someone wet felting. I asked Isa Rodrigues, the director of TAC, what it was and if we were going to do it. Then COVID-19 hit, and classes were canceled, but my interests were piqued. I started watching YouTube videos to learn. We were allowed to work in the studio, so I would go and try things out. I was just making abstract work at first, but then I began to work with images. I knew right away it was something. I could feel how alive the work was. One day Isa said, “I know you like wet felting, but I think you might like needle felting.” Needle felting involves stabbing the felt with barbed needles into a backing to interlock the wool fibers. She left a little Ziploc bag in my cubby with needles and foam and told me to try it.

Since then, I've been teaching myself. I have tried using all kinds of materials as the substrate. I began with silk, since I already had printed photographs onto silk. I tried bark paper from Mexico. Then I began using rug and carpet pads, which turned out to be perfect, especially because it is easy to access.

JS: Can you talk about your image archive? I know you have worked mainly from images pulled from your own photography and family albums.

MJ: I started using my family archive right after my dad died. During the pandemic, there was such a feeling that the future was unknown, so it felt like a moment to look to the past. The archive was a place of inquiry and curiosity.

Lately I haven’t been using the archive; it just isn't offering me that feeling. My mother passed away about a year ago, and since then I’ve been working outside of the archive. It may be too soon, but I haven’t felt my mother’s presence when I’ve made images of her. With my dad, every time I made a likeness of him, it felt like he came back for a moment. I know if a piece is good if it captures this essence. For a moment, it becomes animate, and then it goes back to being wool.

Instead I’ve been focusing on collaboration, like my collaboration with Kim Dacres last year at Art Basel Miami Beach. Recently I had a show in Berlin and I collaborated with a friend of mine who is a poet. It was centered around themes of censorship in both places. She wrote a poem that referenced Dante, and I used that as a point of reference for the imagery.

I do feel a responsibility to contribute to the conversation around diaspora and biracial identity in terms of image-making. How do Brown and biracial people move through space, and how are we allowed to move through space? In my family archive, the Irish family and the Indian family are very culturally separate but they are part of the same archive.

JS: I’m curious about how the work has evolved over the last five years. It seems to have gotten much more complex in terms of the painterly qualities you’ve been able to draw out in the felt.

MJ: I had never felt so comfortable with a material before, especially one I hadn't used, when I found felt. But I think I have been training my whole life to work with it. I could take everything I knew about painting and apply it. I also applied everything I knew about sculpture, photography, composition, design, and art history. If I had started felting at 20, I don't think I would have made this work.

However, it is interesting to have found a medium that I so authentically identify with at age 40. I sometimes wonder if this is what people feel like when they decide to get married: that they’ve met so many people, but that this is the person they want to marry.

I am working on a piece with a black ground, showing a man lighting a Fourth of July sparkler. I’ve been thinking of how I can create transparencies in felt, and how I can make a surface look metallic, when, by nature, felt is not a transparent medium. I am still learning how to create these effects in wool, and it is trial and error.

JS: I’m curious if you think of your work as paintings in felt. In general, what do you think of as your artistic lineage?

MJ: I consider myself coming from a painting lineage. They are absolutely paintings in felt. They are not felt for felt’s sake. I want them hanging next to paintings, and I want them discussed in the same way. But what I also like about them is they are always a little bit wonky. So it is hard to take them overly seriously.

I think of them as sincere and to me, sincere is a compliment. My personality is a bit whimsical and weird. Maybe this comes from a certain survival mechanism I’ve developed. Living in a Brown body, and being a woman, I learned to be disarming. Being quirky and funny is a way to not come off as a threat. Of course, I’m also extremely dedicated, ambitious, and thoughtful. Our art is reflective of us.

I don't think I'm as badass as her, but Faith Ringgold is a hero to me. I think something that I'm naturally inclined to do is to push form. I want to do something with the material that other people haven’t done.

There are not many people working like this. I’m thinking about my work in direct conversation with the history of painting, and also with contemporary painters. There is one Austrian artist, Marlon Wobst, who does wet felting and makes beautiful work that feels related to Katherine Bradford's paintings. Wet felting creates a structural change in the molecules of the wool. It is water repellent, antimicrobial, and fire retardant. It is a renewable resource that doesn’t hurt the animal. The process is so beautiful and simple, but you do need a lot of people working in community to make a big piece.

The way that I work with the wool is reversible. If you don't like it, you can pull it out. But the more the wool is stabbed, the more embedded it becomes. I like that quality of needle felting: They are not fixed. They won't move on their own, but they could be reclaimed in a post-apocalyptic world if people needed to make some blankets quickly. The color may break down over time, and I am okay with that. We can’t keep everything forever.

It is important to me to reconcile opposing things: hard and soft, found and made. That is why I have been combining the felt with clay bodies or embedding it in found objects, like wood boxes, on bricks, or in utilitarian metal objects. It is connected, for me, to being biracial. My work is always a search for wholeness.