The Good, the Bad, and the Forgettable at Frieze New York

The latest edition of the mega-fair is full of extremes, from the very high temperatures during the first day of previews to impressively bad booths and plenty of strong, thoughtful presentations.

Frieze New York is back, and the 2018 edition of the mega-fair may be the most underwhelming ever. There was plenty of griping at yesterday’s very-VIP and press preview about the sweltering temperatures inside the fair and its confusing new layout, but the bigger problem was the lackluster work on view. As ever, there are strong individual works peppered throughout and some standout solo and thematic booths, but by and large the fair feels very by-the-numbers, with major galleries playing it extremely safe and smaller outfits struggling to stand out.

The most immediately evident change at Frieze this year is the new tent, by Universal Design Studio, which consists of a series of discrete and interconnected clusters instead of one continuous, curving space. The result, simply put, is that Frieze now feels a bit more like every other art fair. It also means that visitors can’t easily look up, judge the proximity of the end of the tent, and gauge how many booths they still have to see before the fair closes. The booths themselves are airy and spacious for the most part, and a few galleries (including Gagosian and Stephen Friedman Gallery) even have more than one.

What’s being shown in the booths is, in general, no different from what you’d see on a given day of gallery-hopping in Chelsea, but there are exceptions to this of course. New York’s Donald Ellis Gallery has devoted its booth to a superb selection of Native American ledger drawings. São Paulo-based Galeria Marilia Razuk is showing an array of amazing sculptures by the late Mestre Didi based on the sacred objects used in Brazil’s Afro-Brazilian Candomblé religion. New York’s Lyles & King and Ryan Lee galleries have solo showcases of incredibly fresh, decades-old paintings by Mira Schor and Emma Amos, respectively. Toronto gallery Cooper Cole has a booth of very tactile and uncanny figurative sculptures by Tau Lewis — which, happily, were totally sold out after the fair’s first day. Glasgow-based Mary Mary has a fantastic booth of ceramic, iron, and wood sculptures by Jesse Wine. And Brussels gallery Rodolphe Janssen has an array of lovely woodcuts, paintings, and ceramic sculptures by the twin artist duo of Gert and Uwe Tobias.

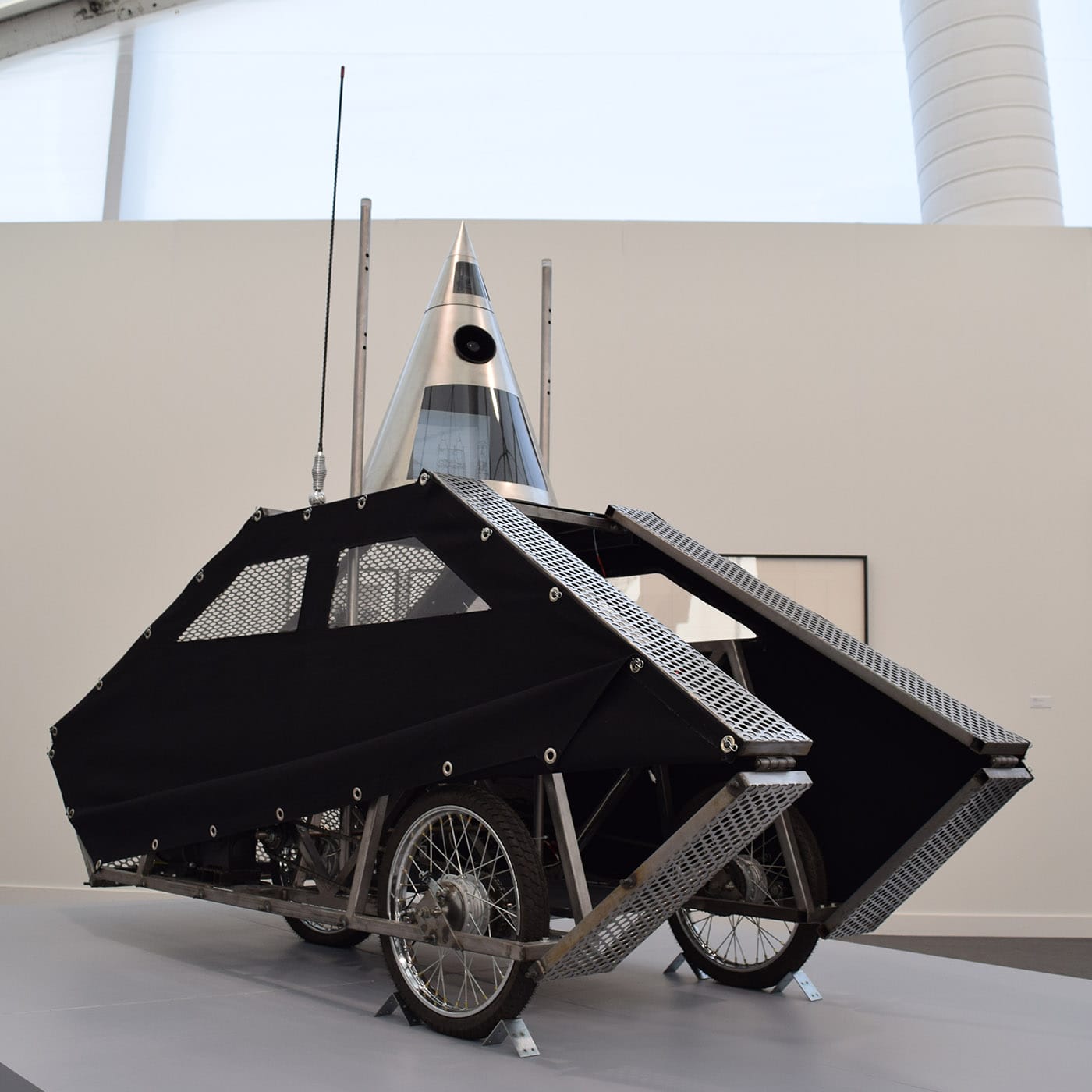

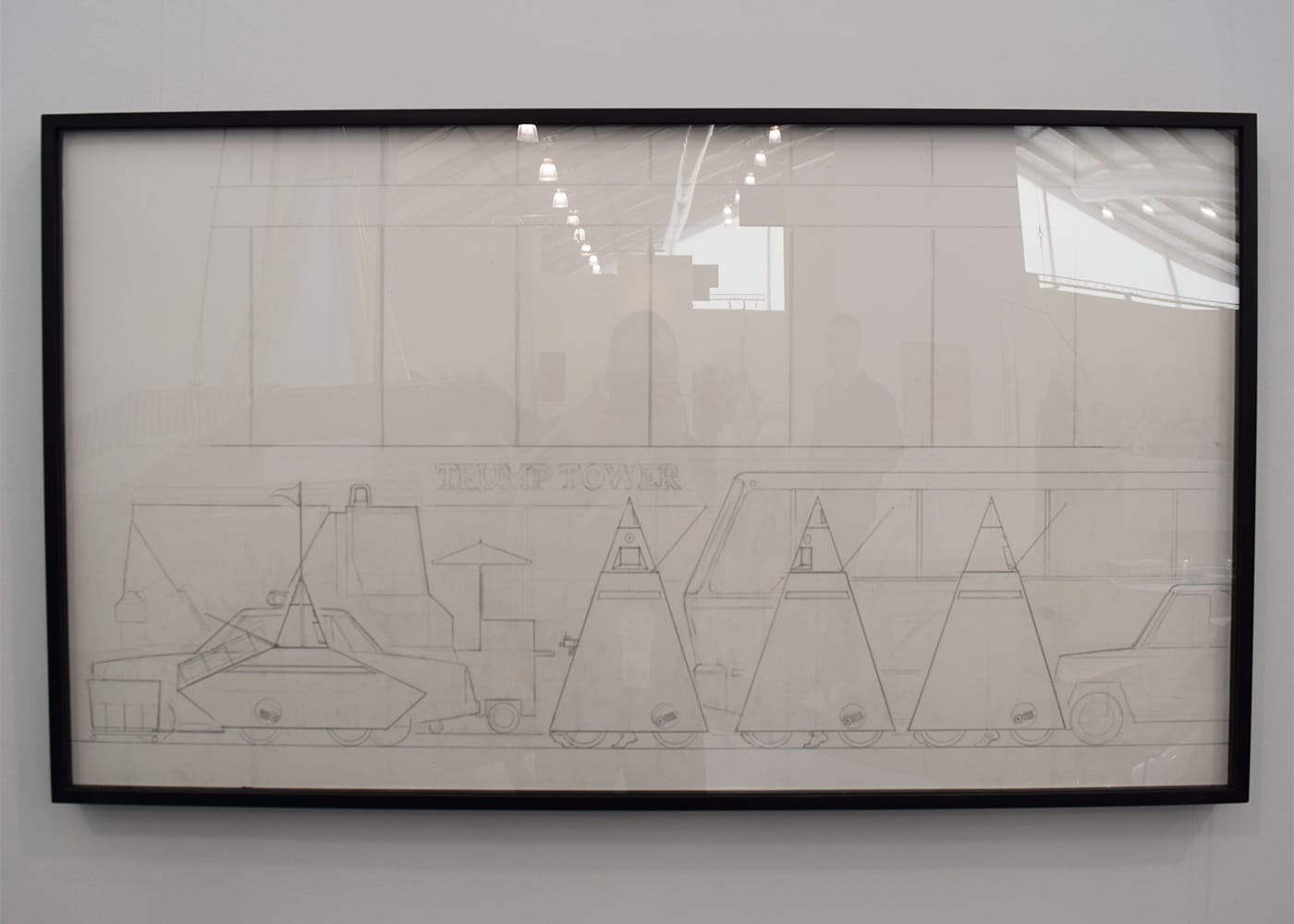

Other booths distinguished themselves with special projects and show-stopping individual works. New York-based Anton Kern Gallery is presenting a solo project by Lara Schnitger as part of the fair’s Live program that will be intermittently activated by a feminist procession through the fair. And there are individual works that rise above the din, like Ann Agee’s delightful spread of ceramic shoe sculptures (“Hand Warmers,” 2017–18) in the PPOW Gallery booth and Krzysztof Wodiczko’s whimsical prototype for vehicles for the homeless (“Poliscar Variant 2,” 1991/2017) in the Galerie Lelong booth. The back side of Marian Goodman’s booth is hosting a fundraising display for Downtown for Democracy, a political action committee offering works by Marilyn Minter and others. Such works and installations make the trek to Randall’s Island worthwhile.

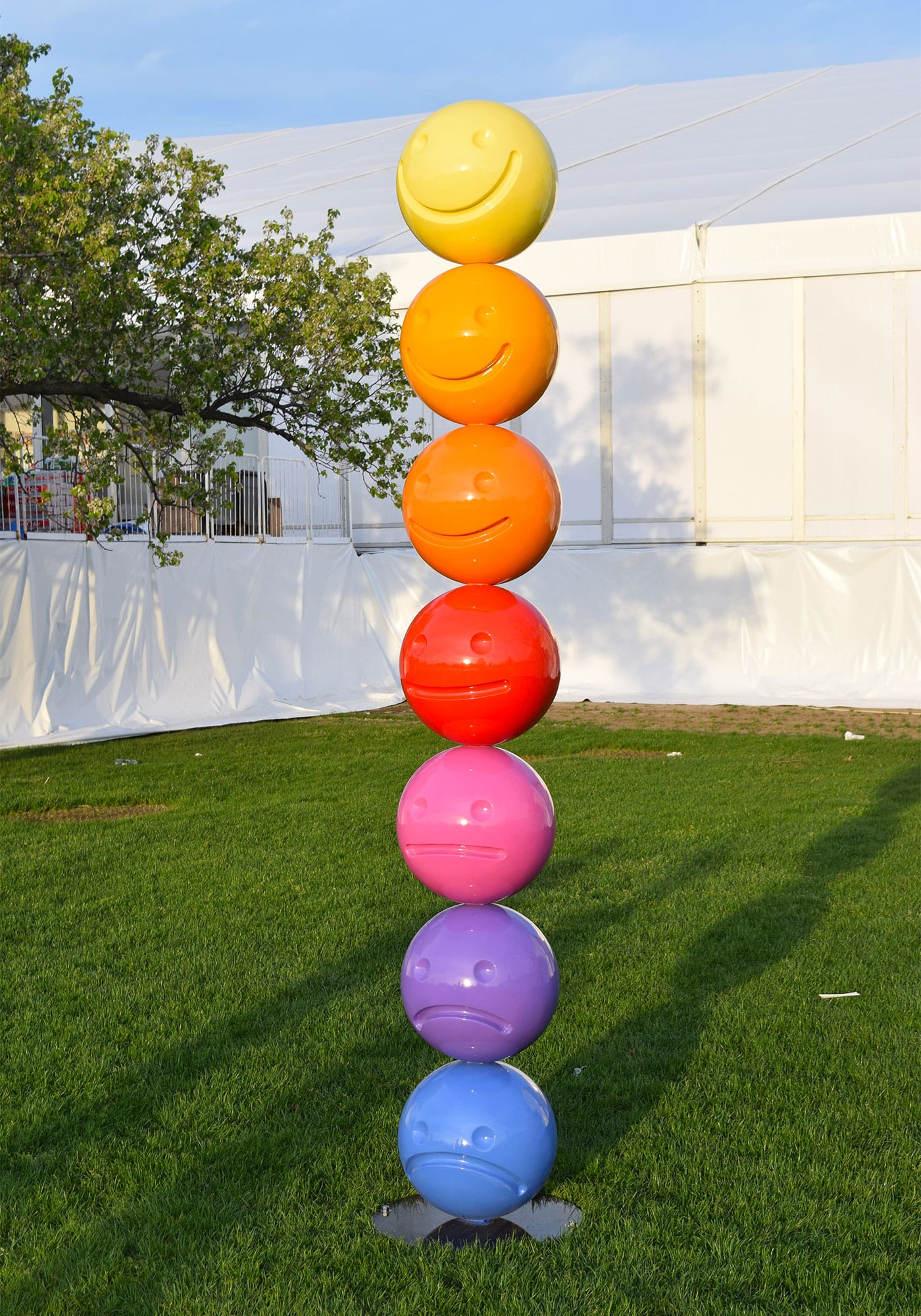

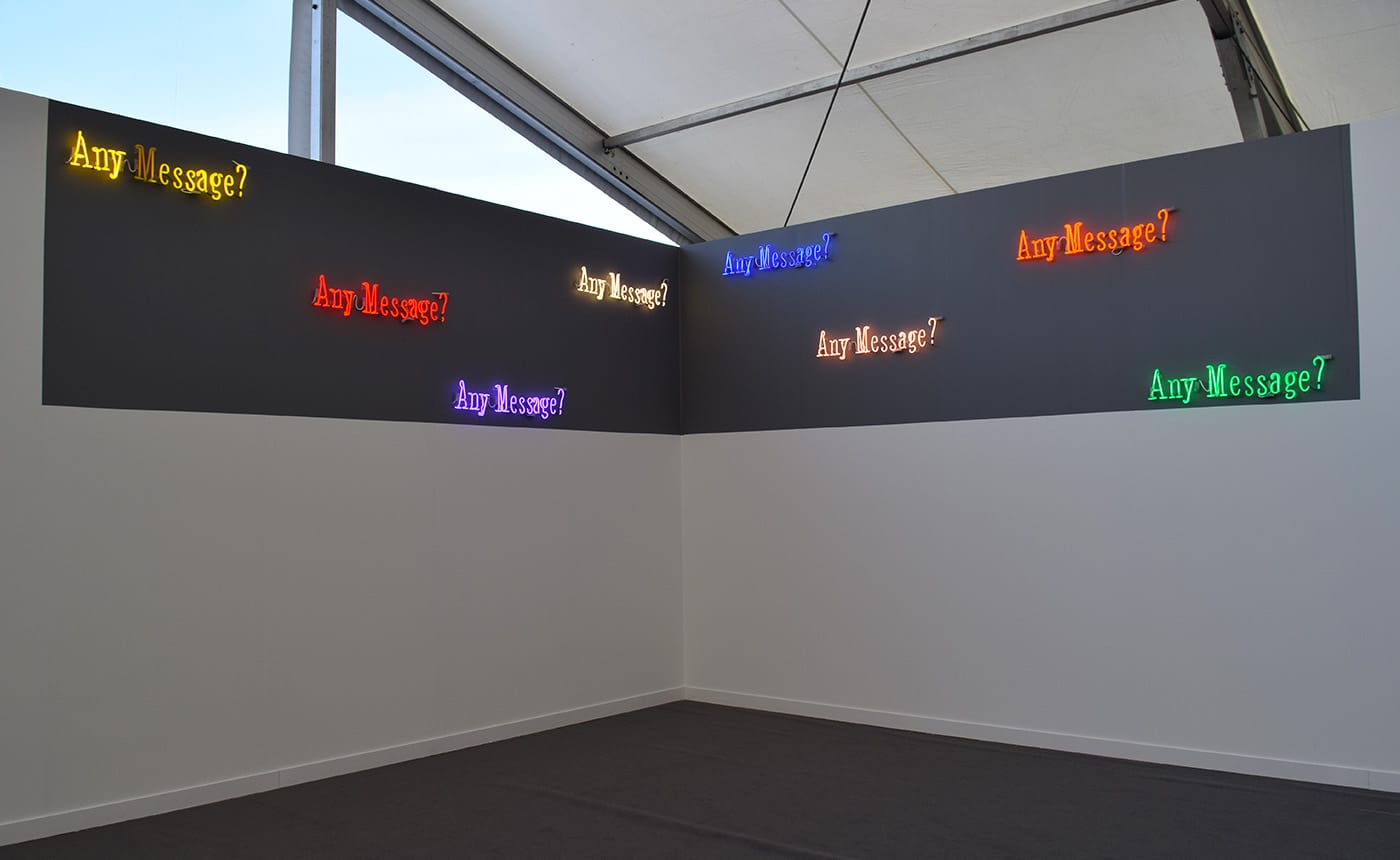

However, for every memorable solo presentation, there are dozens of forgettable booths and plenty of outright bad ones. And, as luck would have it, the fair’s most shameless peddlers of mediocrity are some of the biggest galleries in the world. Almine Rech Gallery has a sad, half-empty booth showcasing Joseph Kosuth neon sculptures and little else. Pace Gallery has an entire booth of David Hockney’s iPad and iPhone drawings, each more uninteresting the next — which didn’t keep collectors from snapping up 30 of them in the fair’s first day. Gagosian, as mentioned earlier, has two booths: one is largely devoted to an installation by Robert Therrien that consists of large-scale and very realistic sculptures of folding furniture that bring the Museum of Selfies sensibility to Frieze; the gallery’s other booth, in a part of the fair devoted to a multi-booth tribute to the late dealer Hudson, features large-scale sculptures and paintings by Takashi Murakami, an artist who showed at Hudson’s gallery, Feature Inc., in the 1980s and ’90s.

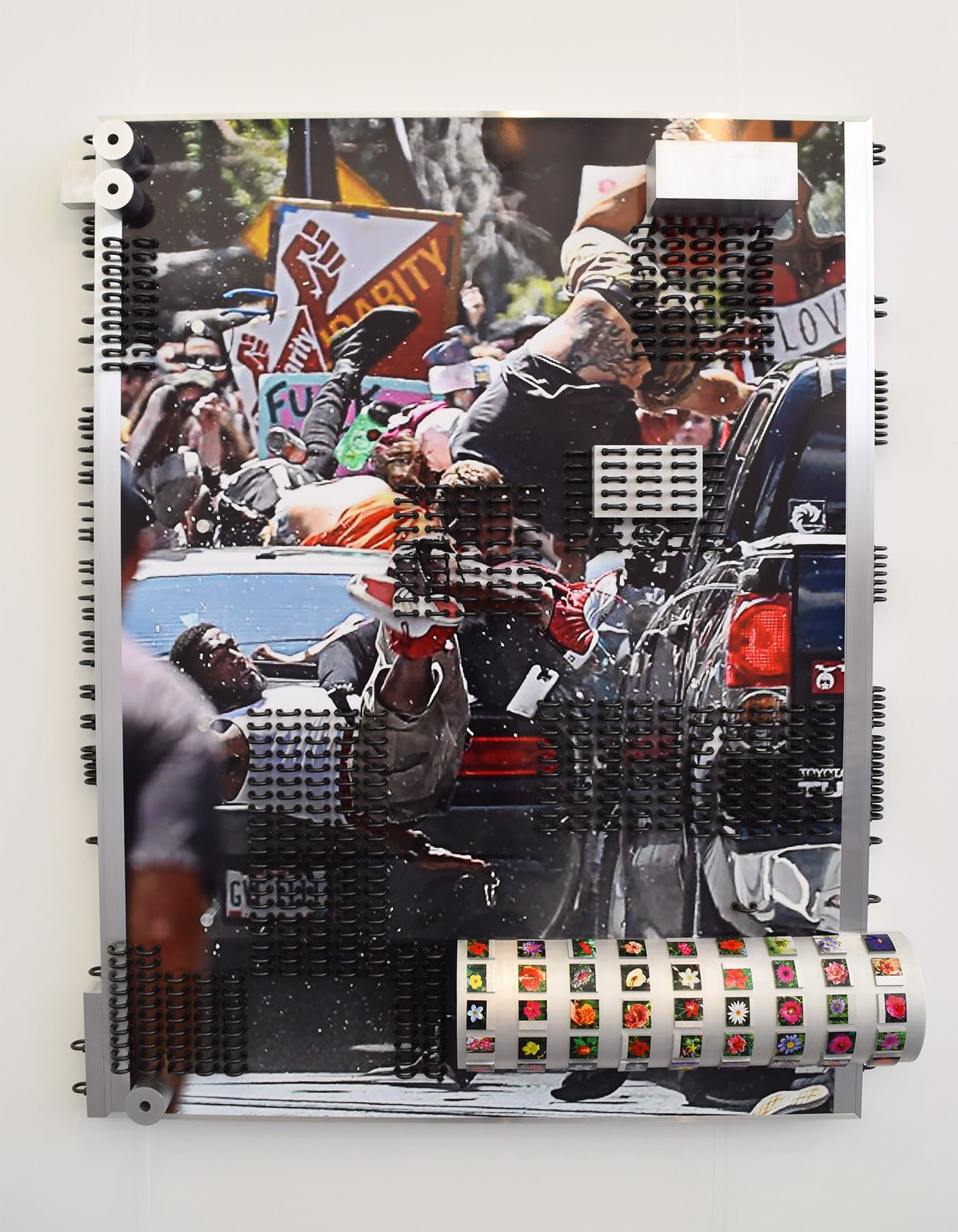

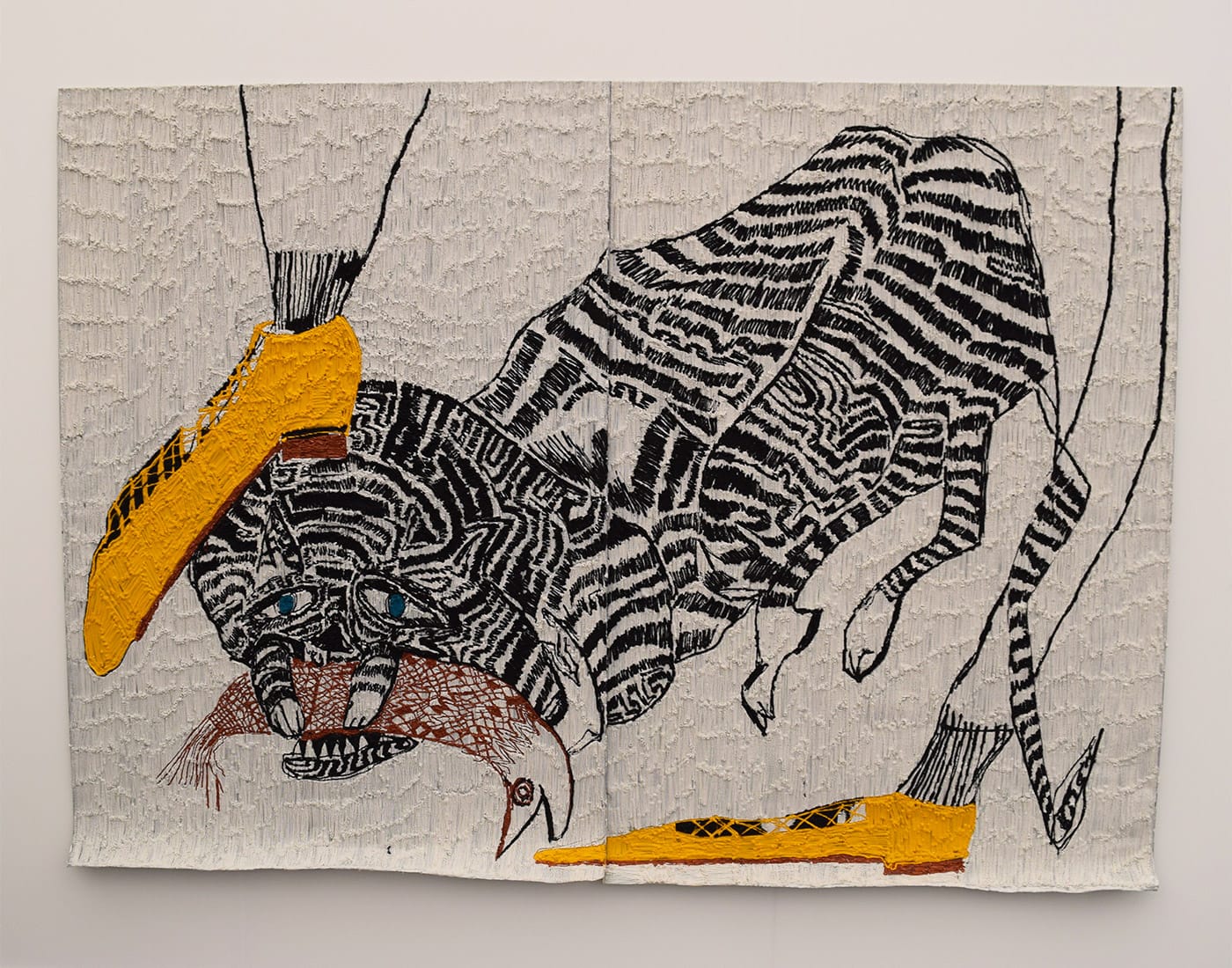

For my money, though, the fair’s worst booth belongs to David Zwirner. Devoted to new works by Jordan Wolfson and Josh Smith, it features the latter’s riffs on images of the grim reaper, and sculptures by the former that evoke some pre-digital computers, printed with photographs of difficult or painful subjects — including the car of James Alex Fields plowing into protesters in Charlottesville in August 2017. I strongly advise steering clear of the Zwirner booth, though the fair’s revamped configuration makes that virtually impossible.

Between its generic new layout and the bravura badness of some its biggest exhibitors, the latest edition of Frieze New York offers plenty of lessons for how not to tweak a winning fair formula. With any luck, by the time May 2019 rolls around the organizers will have reevaluated their decisions and made more changes.

The Good

The Bad

Frieze New York 2018 continues through Sunday, May 6 in Randall’s Island Park (Randall’s Island, Manhattan).