Bland in an Interesting Way

If the War on Drugs’s Lost in the Dream is a brilliant soft-pop masterpiece, a theory I am perfectly willing to entertain, it is brilliant in a way more suited to a platinum bestseller than to a critics’ record.

If the War on Drugs’s Lost in the Dream is a brilliant soft-pop masterpiece, a theory I am perfectly willing to entertain, it is brilliant in a way more suited to a platinum bestseller than to a critics’ record. Notwithstanding the band’s arty reputation, their strength is in their massive riffs and grand musical release, not in the subtleties of their instrumental sound and certainly not in the sensitive songwriting. By the hazy, abstract standards of psychedelic-electronic alternative rock, this album’s clear, pop-friendly shape isn’t just a breakthrough, it’s a marvel. If not for the long synth breaks and stiff textural overlay, half these songs would sound perfectly at home on oldies radio, right alongside Bruce Hornsby’s “The Valley Road” and Don Henley’s “The End of the Innocence”.

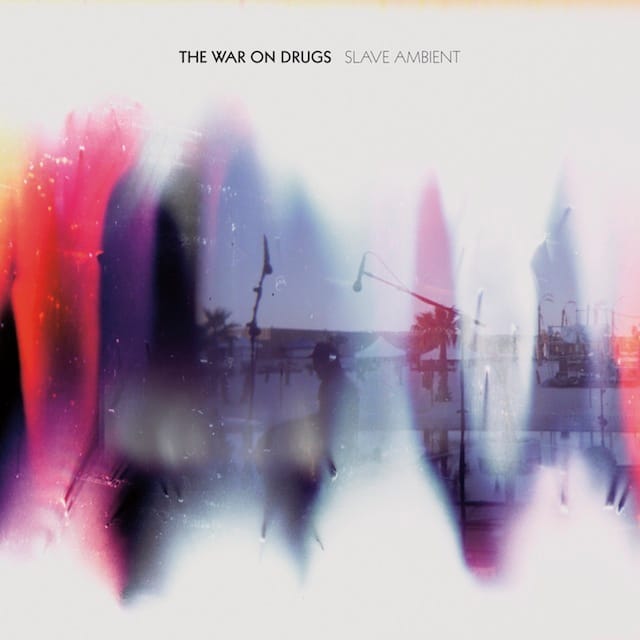

I’m exaggerating, but not by much. Certainly lead Warrior Adam Granduciel writes more fully-formed songs than most of his acid/ambience-damaged contemporaries; certainly he sings more expressively. As with his cofounder Kurt Vile, who left the band in 2008 to pursue a solo career, Granduciel’s music can slide into somnolence at times, and circa 2011’s acclaimed Slave Ambient, the Philadelphia-based band came across like a surprisingly lucid, predictably dreamy instance of the impressionistic, reverb-drenched chillwave that was then igniting the blogosphere. But they’ve since gotten faster and more distinct, with crisper guitar lines and tighter melodies, and even on Slave Ambient if not 2008’s messy Wagonwheel Blues they were jumping up and down with a lot more energy than the norm among most neopsychedelic wizards. Released this March, Lost in the Dream has inspired countless rave reviews highlighting the spiritual torment in Granduciel’s songwriting — “an immaculately assembled portrait of a man falling apart,” quoth Pitchfork’s Stuart Berman, and if you pay attention to the generalized, existential lyrics you might agree. But nobody would have noticed if the band weren’t suddenly rocking a lot more confidently over a strong four-four beat, melding exquisitely engineered guitar and glistening layers of keyboard into a slick stream of hookcraft. They don’t sound happy, exactly, but they do sound relaxed, gentle, and easy to listen to.

In retrospect, Vile’s departure seems like a turning point. Wagonwheel Blues was dominated by shades of the poky, acoustic slacker Americana that Vile has since settled into on his solo albums, but by Slave Ambient the band had already absorbed pulsating slices of keyboard and wobby blasts of guitar riffage into its sound. Lost in the Dream goes even further in its obsessively seamless, shimmeringly electronic smoothness, and where Vile’s exceptionally laid-back roots-rock band and sleepy drawl get by on their charming amateurism, Granduciel has since revealed himself as some sort of crazed studio perfectionist, polishing his songs until they sparkle like shiny rays of Fairlight streaming through a gauzy cloud of stardust. What both musicians share is that they take refuge in blandness — boldly, consciously, as a deliberate aesthetic project, the way bands like Grizzly Bear and the Dirty Projectors take refuge in precious obscurantism, as an antidote to existential displacement, to political alienation, to personal torment. Vile’s blandness generally falls into the lethargic aw-shucks variety, and Granduciel is definitely more beholden to slick late-’80s AOR soft-pop. But despite Granduciel’s indie-electronica bona fides, he does buy into a tame, mild ethos that has roots in both said soft-pop and the studio folk-rock concocted in secret California laboratories by money-hungry former hippies in the early ‘70s. In fact, his tenderhearted side is what makes his music so fascinating, if not quite compelling enough.

Lost in the Dream may just be the strongest bland album I’ve heard all year. Kicking off with the epic, breathless “Under the Pressure” leading into the readymade arena crowdpleaser “Red Eyes,” the musical strategy combines the hazy psychedelic environment that is Granduciel’s chosen sonic playground with the efficient pop production that is his secret love: out of a cold, misty lake, filled with quietly strummed guitar and shiveringly atmospheric synthesizer gloss, rise hulking, enormous anthems that glide with surprising elegance and calm poise, gracefully crooning their refrains to the sky before diving down to crash and dissolve into the waves, flowing back naturally into the pale atmosphere, leaving trails of whoosh and quiver scattered all over the water’s surface. Soaring beneath texture upon pristine texture, the craft inherent in these abundant blankets of blurry synthesizer tone never obstructs its perpetual rhythmic momentum. When megahooks like the ones on “Red Eyes” and “Under the Pressure” and even the wistfully sentimental “Eyes to the Wind” lock into place, there’s no denying their sumptuous, sweeping majesty. When he slows the tempo down for quieter, more thoughtful ballads, however, the loss in drive is palpable, and rid of any formal backbone, many songs are reduced to the shifting and humming of glazed electronic sound effects plus Granduciel’s soft, lonely voice. As an expressive troubadour he definitely has his limits; song topics include fire, wind, the ocean, rivers flowing, the burning in your heart, calling out your name in the darkness, and the arrival of a new day. Even at his most most spirited, even at his hardest-rocking, the pleasure in his music is still dependent on the kind of childishly open emotionalism that always turns mindless, feelgood, passive.

For this wacked-out, experimental band to suddenly and miraculously discover the joys of the catchy pop song represents a definite step forward, not just for them but for their whole genre. But hooks come in all shapes and sizes, and ultimately these add up to a soulful, comforting exercise in escapism for troubled young people. As such an exercise it’s infinitely more intelligent than just about anything the vast majority of their contemporaries has come up with, and rather more musically rewarding, but the music does falter. No matter how you put it, we have here a subculturally respected, critically celebrated alternative rock band who sound almost exactly like Bruce Hornsby. Something is very wrong in the world.

Lost in the Dream and Slave Ambient are available through Amazon.com.