Contemporary and Historic Ledger Art Joined in a Seamless Native Narrative

Too often museums exhibit indigenous art of the United States as artifacts made by ghosts, even though many of these traditions are still inspiring contemporary creators.

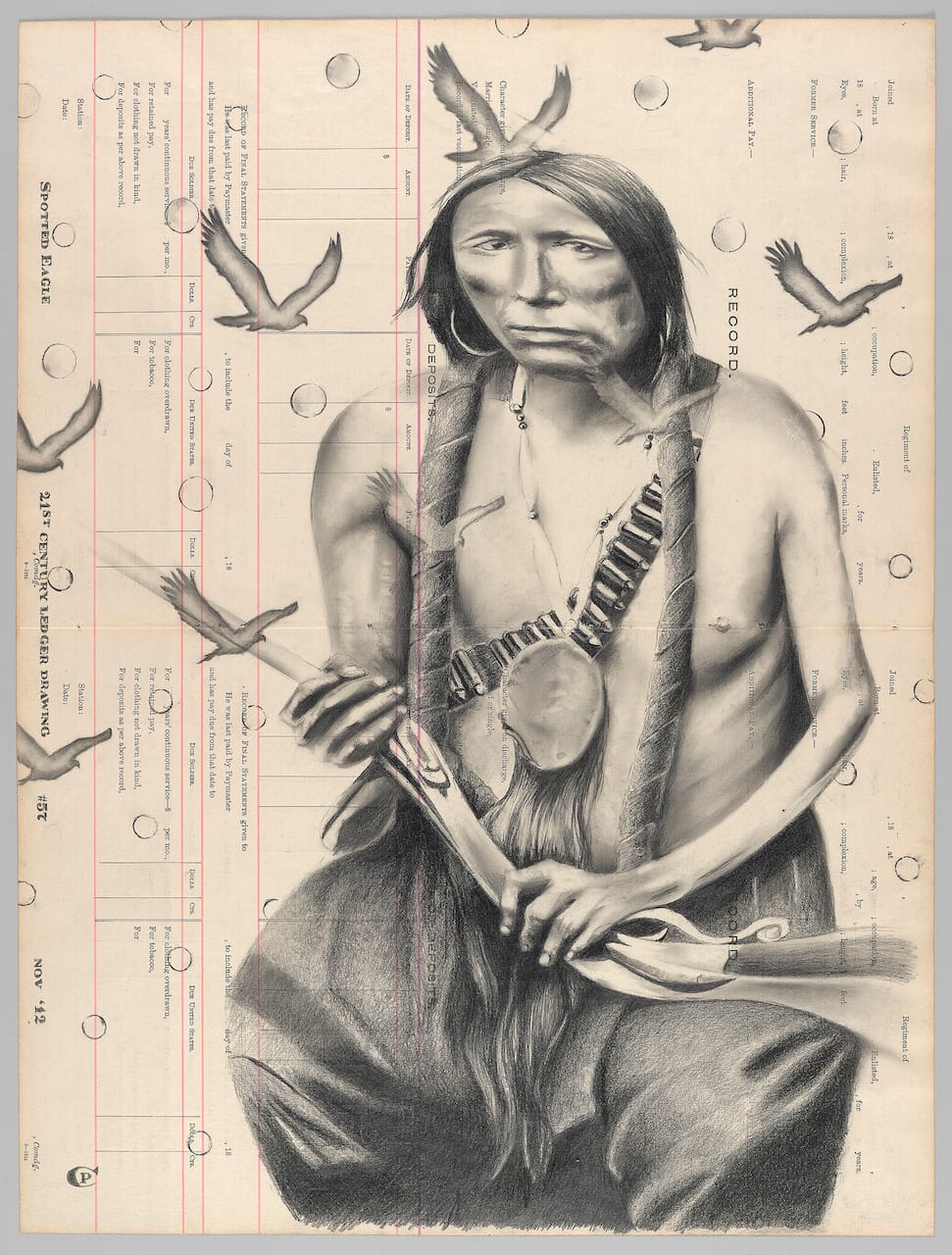

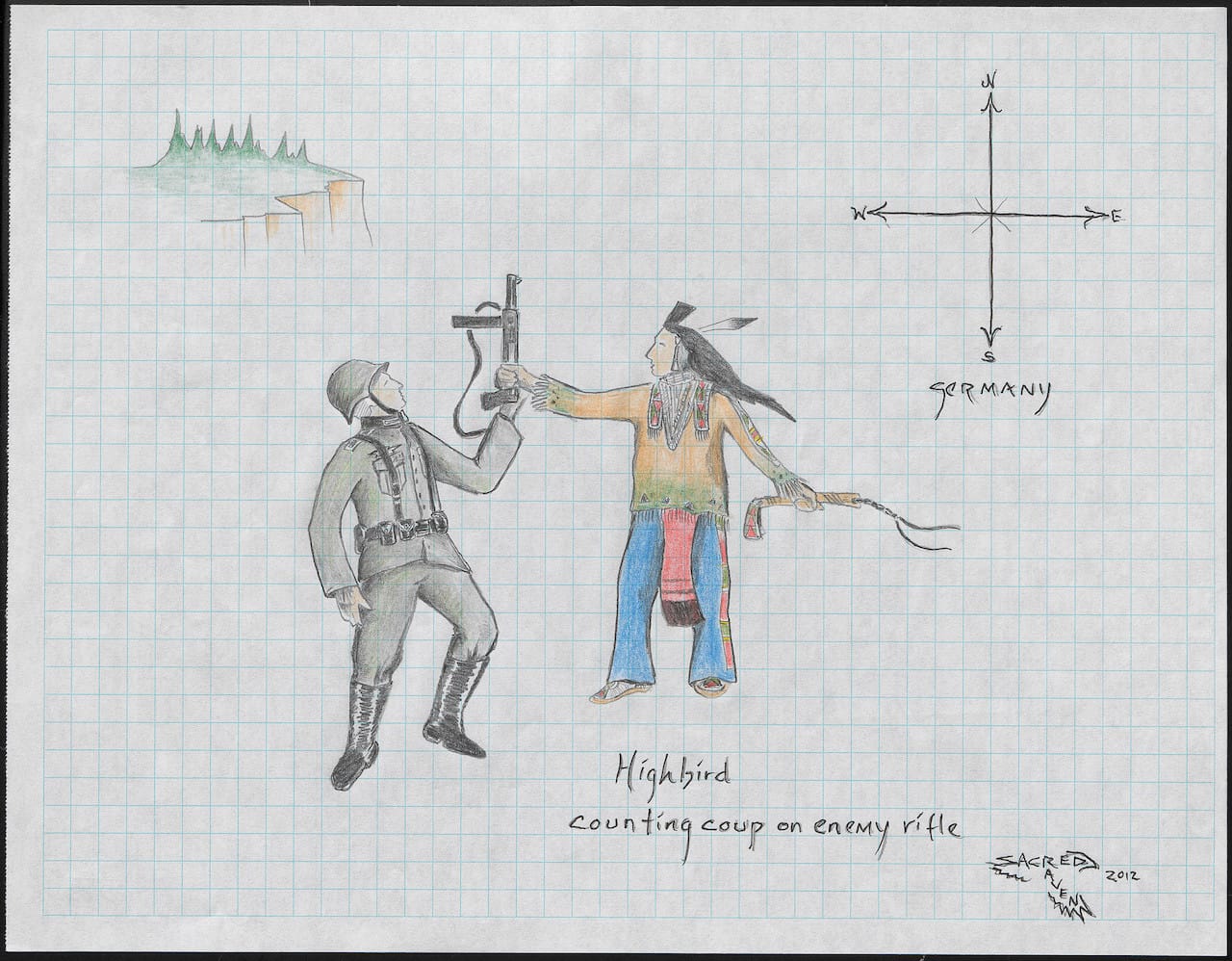

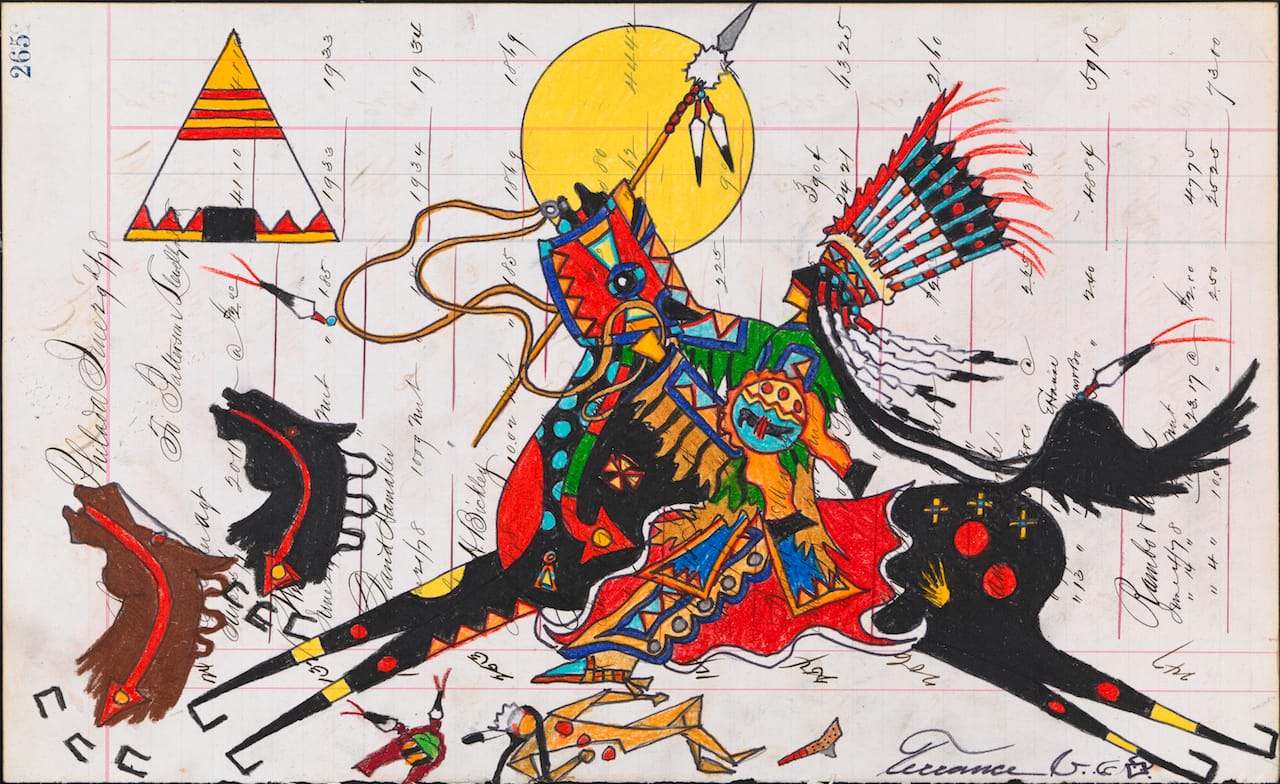

Too often museums exhibit indigenous art of the United States as artifacts made by ghosts, even though many of these traditions are still inspiring contemporary creators. Unbound: Narrative Art of the Plains, which opened this month at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian in New York, showcases commissions from 16 contemporary artists alongside historical pieces, focusing on the revival of the ledger art style that first emerged in the 19th century.

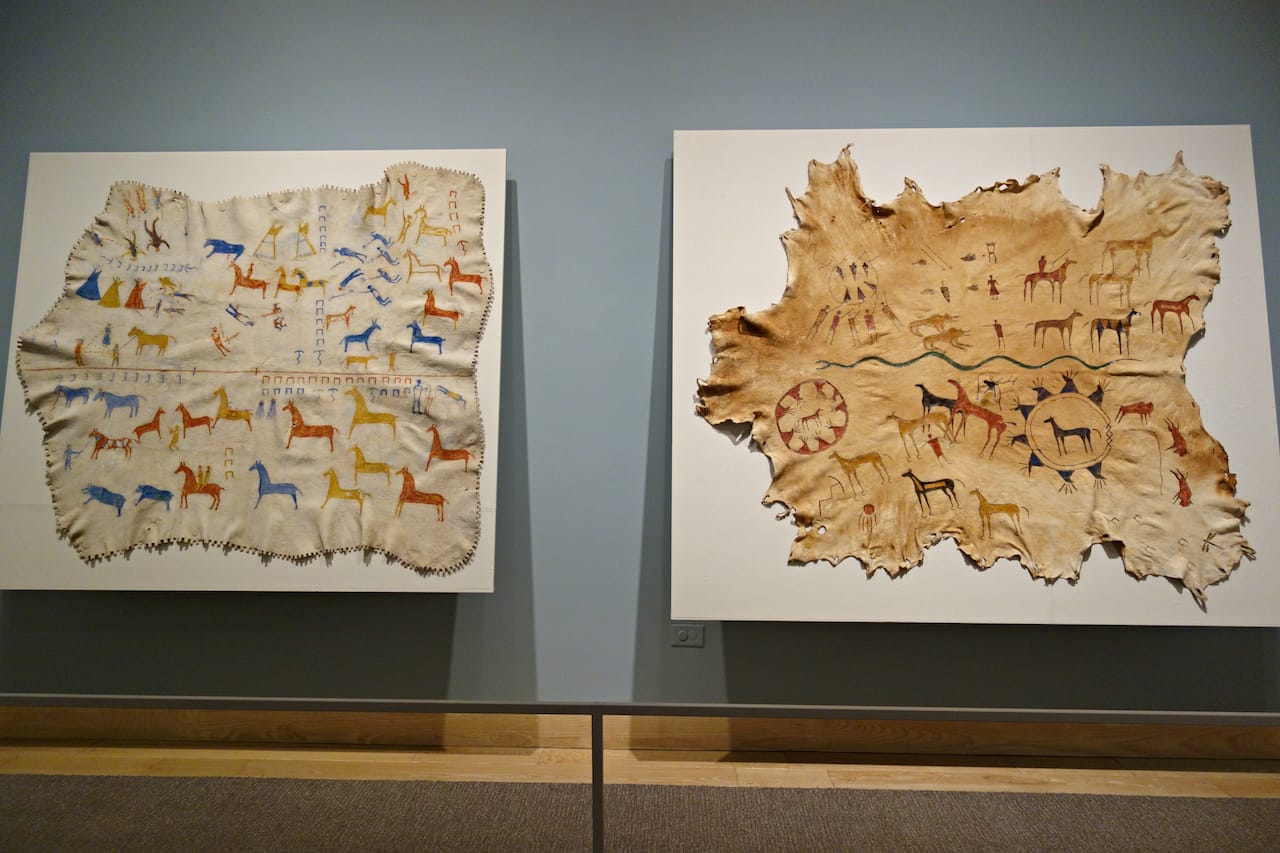

Unbound feels tonally different from last year’s The Plains Indians: Artists of Earth and Sky at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, organized by the Musée du Quai Branly in Paris with the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City. While that exhibition gave a small space to contemporary art at its conclusion, those works were presented more as a rebirth from cultural destruction under colonization than a continuation. It was also a show where Native people were consultants, not organizers.

Curated by Emil Her Many Horses, a member of the Oglala Lakota Nation in South Dakota, Unbound displays historical and contemporary art side by side. Lauren Good Day Giago painted a dress to celebrate the Vietnam service of her grandfather Emery Good Bird Sr. (Blue Bird), joined by a 1880 Hunkpapa Lakota dress that would be worn by women to honor fallen warrior relatives. David Dragonfly similarly painted an elk hide with scenes from the military career of his great-grandfather Little Calf, which is displayed by a Blackfeet elk skin robe from 1920. James Yellowhawk painted on a small model of a Coleman tent with the night sky and a buffalo hunt, a modern response to the neighboring Lakota tipi model from 1890.

These objects are the focus of the first gallery, with the other rooms concentrating almost exclusively on ledger art. The medium gets its name from the discarded ledgers used in the 19th-century for illustration, many coming from places like Fort Marion in St. Augustine, Florida. A couple of historic ledgers are presented with digitized displays to flip through, such as the 1875 ledger by Fort Marion prisoner Bear’s Heart, a Southern Cheyenne warrior.

Ledger art might feel like a reminder of colonialism and the loss of Native land and independence, but it was also an essential expression of a Native perspective at a time when their voices were being silenced. For example, the 1881 ledger by Red Horse currently on view at the Cantor Arts Center at Stanford University shows a Lakota Sioux warrior’s eyewitness account of the Battle of the Little Bighorn, a major contrast to 19th-century romanticizations of Custer’s “Last Stand.”

Later in the 20th century, ledger art took on a new life with artists like the Kiowa Six and Woody Crumbo adopting the characteristically flattened perspective, and the style persisted through the 1960s and 70s with the American Indian Movement. Artists in Unbound vary between traditional scenes like Terrance Guardipee’s vibrant depictions of Blackfeet history, and contemporary dancers at a powwow holding smartphones in one of Dwayne Wilcox’s playful drawings.

The blurred timeline is similar in a way to the disjointed narrative structure of the documentary INAATE/SE/ [it shines a certain way. to a certain place./it flies. falls./], by brothers Adam and Zack Khalil, recently screened at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), which explores Ojibway identity in the 21st century. Unbound loosens the usual museum chronology by emphasizing the contemporary as much as the historical, which makes each aspect feel more powerful than it would on its own. In a buffalo hide piece by Dallin Maybee, called “Conductors of Our Own Destiny,” warriors hunt buffalo in hotrods and motorcycles, and one figure is visibly conducting a locomotive. Ledger art, and these other forms of pictorial storytelling, are narratives for neither the past or present, but for a timeless cultural dialogue.

Unbound: Narrative Art of the Plains continues through December 4 at the National Museum of the American Indian (1 Bowling Green, Financial District, Manhattan).