Creating a Dream World in Black-and-White

It takes only one Academy Award for critics to claim a resurgence of genre, and when The Artist won the 2012 Oscar for Best Picture, it was heralded as signaling the return of an interest in black-and-white silent film. Blancanieves, the latest film from Spanish director Pablo Berger (Torremolinos 7

It takes only one Academy Award for critics to claim a resurgence of genre, and when The Artist won the 2012 Oscar for Best Picture, it was heralded as signaling the return of an interest in black-and-white silent film. Blancanieves, the latest film from Spanish director Pablo Berger (Torremolinos 73) would seem to be a continuation of that (rather small) trend — except Berger’s film was already in production at the time of The Artist’s release. Rather than owing its creation to The Artist’s success, then, Blancanieves points to a simultaneous, transoceanic interest in black-and-white silent film, outside of the usual film-school experiments. (It’s important to note that “silent” refers only to the absence of audio dialogue; even in the early 1900s, live musical accompaniment was standard.)

Film is a 20th-century art form, and the popular perception of older movies tends to be that they are touchingly sincere, belonging to an archaic zeitgeist. As the earliest manifestation of the medium, black-and-white silent film often gets treated as the most outdated. Berger gladly indulges these presuppositions by presenting a story that is emotionally honest to its core.

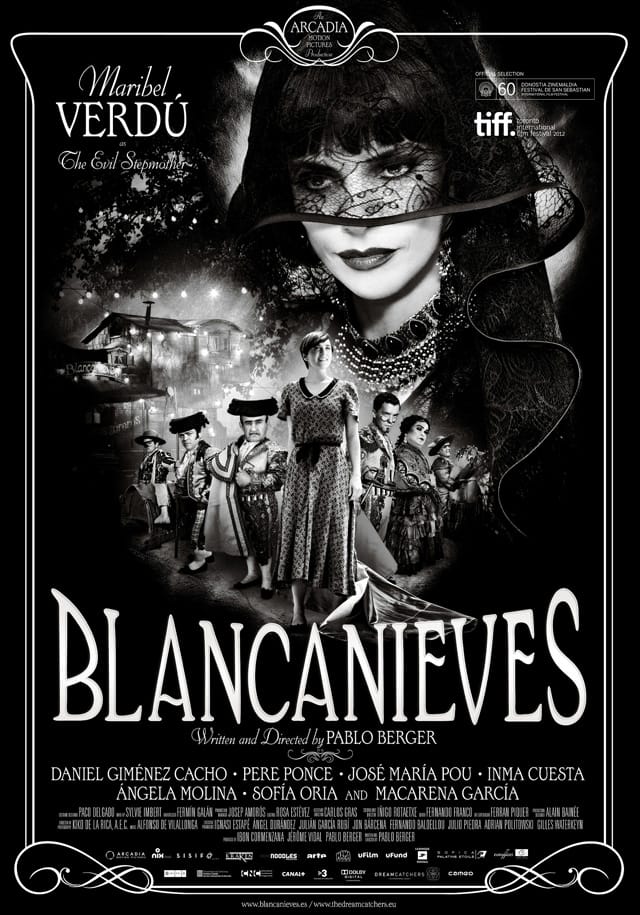

Based on the Brothers Grimm’s “Snow White” and set in 1920s Spain, Blancanieves tells the story of Carmen, whose beautiful flamenco-dancing mother died in childbirth, and who is raised by her evil stepmother (played brilliantly by Maribel Verdú) and her father, once a famous bullfighter but now paralyzed. The film’s sincerity comes through in its treatment of tragedy: Young Carmen is playing at flamenco dancing with her grandmother, when suddenly her grandmother falls to the ground, dead. The child has lost the only loving presence in her life, and in a way that brutally enlightens her to the fickleness of happy moments. A bit later, Carmen has finally eluded her stepmother and sneaks into her father’s room. She plays him a record of her mother singing flamenco and spins him around in his wheelchair so he can feel the sensations of movement once more — a wonderfully perceptive and touching demonstration of a daughter’s love.

The emotion in these scenes doesn’t come from exaggerated facial expressions or cheesy title card dialogue, ways in which the popular imagination has enshrined silent film. Rather, Berger presents us with a new vision of what black and white is about. The Artist seemed to relate to its predecessors by keeping a militantly tongue-in-cheek tone; the trademark of the female lead, Peppy Miller, is, fittingly, a wink. In contrast, Berger’s images are dramatic tributes to the human form: the dark eyebrows of a beautiful woman as they contrast with a white lace shawl placed over her head; a child’s eyes as they widen in fear and become small caverns; a matador raising his sword and narrowing his eyes at he fixates on the bull; the hem of a woman’s dress flying back and forth as she dances flamenco; full lips falling into an innocent smile; a mother’s mouth widened in a scream of pain as she realizes her daughter is dead.

By mixing emotional authenticity with powerful visuals, Berger upsets preconceived notions of the black-and-white silent genre, enough for the audience to accept other, more contemporary elements: behind closed doors, the evil stepmother has a humorous penchant for dominatrix activities; one of the male dwarves cross-dresses; and perhaps most importantly, the film ends with an ambiguous scene that suggests depression and unrequited love. Before she eats the apple, Carmen and one of the dwarves appear to have fallen in love. But in her subsequent slumber, he kisses her and she does not awake, although a single tear slides down her cheek. The love that the audience assumed would wake her may not be true — or perhaps she wakes up, sheds a tear, and chooses not to return to the world of the living.

Blancanieves reminds viewers of the unique potency of film’s original form. Black-and-white silent films have a power similar to that of magical realism — the audience can suspend disbelief because the rules of perception are fundamentally different from the start. Berger reminds his viewers that film is like a dream: all the elements of the real world are there, but they may be rearranged, named differently, and appear in strange forms; time follows different rules, and dialogue is impressionistic instead of continuous. Berger’s artistic clarity offers viewers an alternate reality, one whose emotional power we may have temporarily forgotten.

Blancanieves is currently playing at the Angelika Film Center in New York (18 West Houston Street, Soho, Manhattan) and other select theaters around the country.