Crossed Wires in a River of Glue

Julieta Aranda’s latest work on view at the James Fuentes gallery, has the patina of social significance and discernment.

Julieta Aranda’s latest work on view at the James Fuentes gallery, has the patina of social significance and discernment. Yet, though the work draws into play some potent symbols of our irrational relation to our planet and its resources, what is given the viewer of Swimming in Rivers of Glue (an exercise in counterintuitive empathy) are only gestures towards insight.

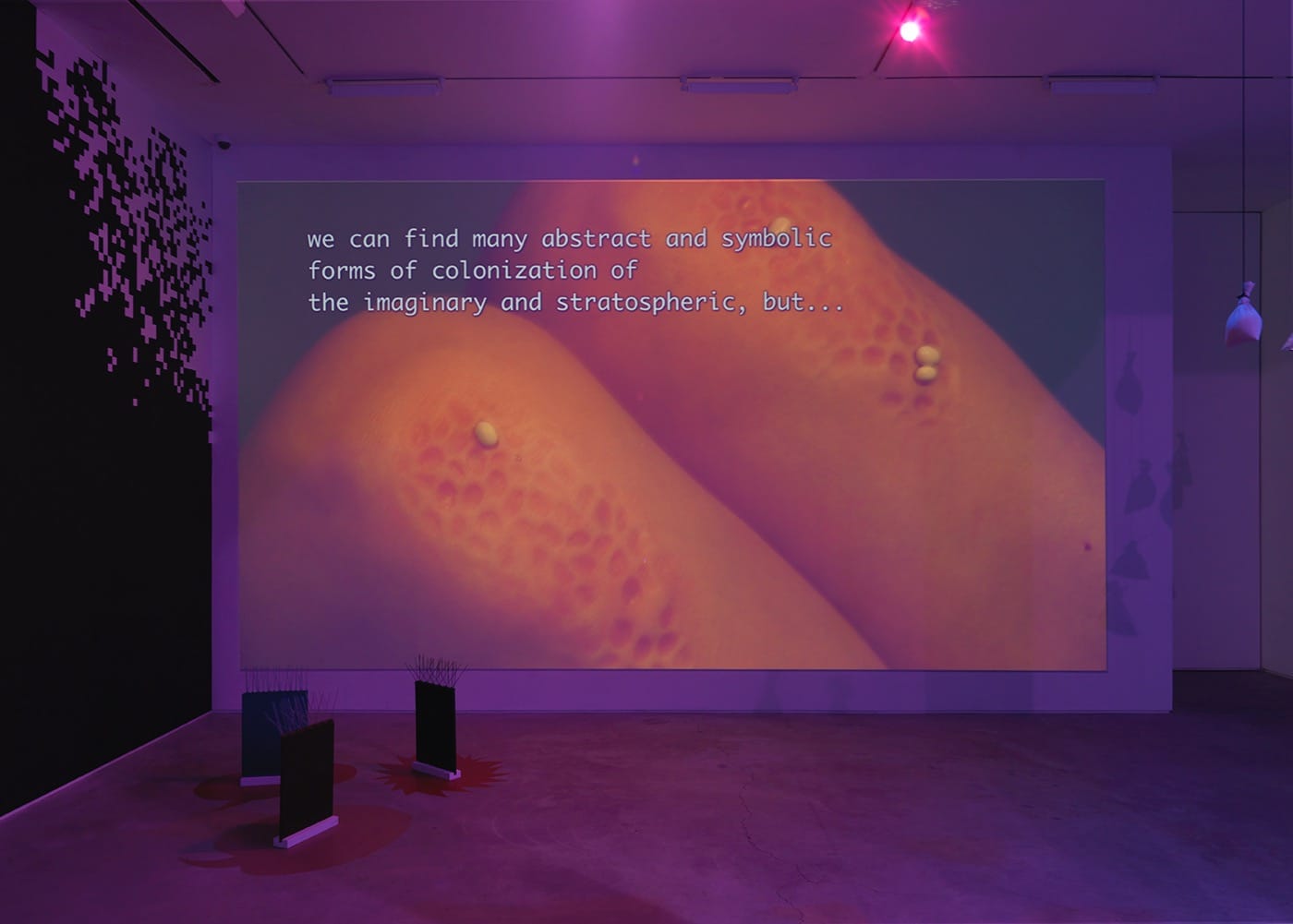

This is not so clear initially because the show is visually alluring. To experience it, one enters the gallery through a dark and heavy curtain, the lights are dimmed inside to accommodate the video screened against one wall. In the one main room there are small families of concrete or stone sculptures: cones, balls, and rectangles with tops angled at 45 degrees (like New York’s Citigroup Center building). On the wall opposite the video, are small, framed, mocked-up spider webs and then a large, mock spider web hung between an exposed beam and a wall. There are bookshelves containing one or two books guarded by broken glass. Bags of water, some containing coins are suspended from the ceiling, small rectangular structures like miniature office buildings sprouting spikes of the type that are employed to keep birds from alighting on them. On another wall is a crossword puzzle with provocative terms that include: “ideational,” “transported,” binding,” “empty,” “spacetime,” “drive,” and “essentialism.” Together the objects feel like the home of a tribe whose cave I’ve stumbled inside, and they’ve left the TV on by mistake. The images that flow through the video, and the text that accompanies them, do register as important. I should be able to use these images to suss out who these people are and what they’re about: an unyielding tangle of telephone or electric wires, a wave of lava devouring a can of Monster energy drink, smoke billowing out of an industrial chimney, a praying mantis eating a lizard slowly.

These signs seems to add up to Aranda saying something about how we as a species are moving toward an “explorocracy” as the risks to our survival become harder to deny. As the video depicts, it seems increasingly that “our priority is survival at any cost.” I’m told by the sales director Katrin Lewinsky that this exhibition is the second half of the installation presented at the 2014 Berlin Biennale, “Stealing one’s own corpse (An alternative set of footholds for an ascent into the dark)” (2014), which was reportedly generated by Aranda’s experience of zero gravity, propelling Aranda to think about body experiences, science fictional ideas, and the issue of recurrent global crises. That work displayed a series of snares and traps that read as brought about by our desire to acquire and dominate. A similar concern is mirrored in this show in the instruments of capture and organization (plastic bags, molded concrete), and the tools that keep other life forms at bay, the spikes for birds, and the jagged glass for keeping other animals from our accumulated knowledge.

However, the natural world, indifferent to our narcissistic self-regard keeps moving, flowing, and eating — the lava reduces everything in its path to ash or steam. This is a worthwhile notion to explore and unpack, but the show flits from one meaning to another like a bird looking for ground on which to settle. The video asserts that “ugly cities have great futures,” and that we exists in “a world mediated by a false image of the world.” Both of these phrases are provocative enough to pique a viewer’s interest, but the integument that connects them is never found, at least by me. The show gives us a few hot potatoes to throw from hand to hand long enough for them to cool all the while imagining that they will be worth digesting.

Aranda has previously made serious, compelling work that cleverly contemplates the nature of time, what underlies our dreams of space travel and colonization of other planets, the sometimes arbitrary relation of science fiction to lived reality, but here the work recycles some of the earlier strategies and objects without achieving coherence. In one arc of the video an octopus tries for some time to unscrew the jar it’s locked in and when it finally does, it’s free. Yet, immediately upon figuring out it can get out, it goes back into its too small prison. Yes, we might take from this that humanity has grown accustomed to the prison of its bad habits, but is there more?

Julieta Arenda’s Swimming in Rivers of Glue (an exercise in counterintuitive empathy) continues at James Fuentes (55 Delancey Street, Lower East Side, Manhattan) through June 19, 2016.