Curating a Show on My Ineffable Mother, Ursula K. Le Guin

I would never have proposed this exhibition in her lifetime. This is, after all, a writer who said in an interview, “Don’t shove me into your damn pigeonhole, where I don’t fit, because I’m all over.”

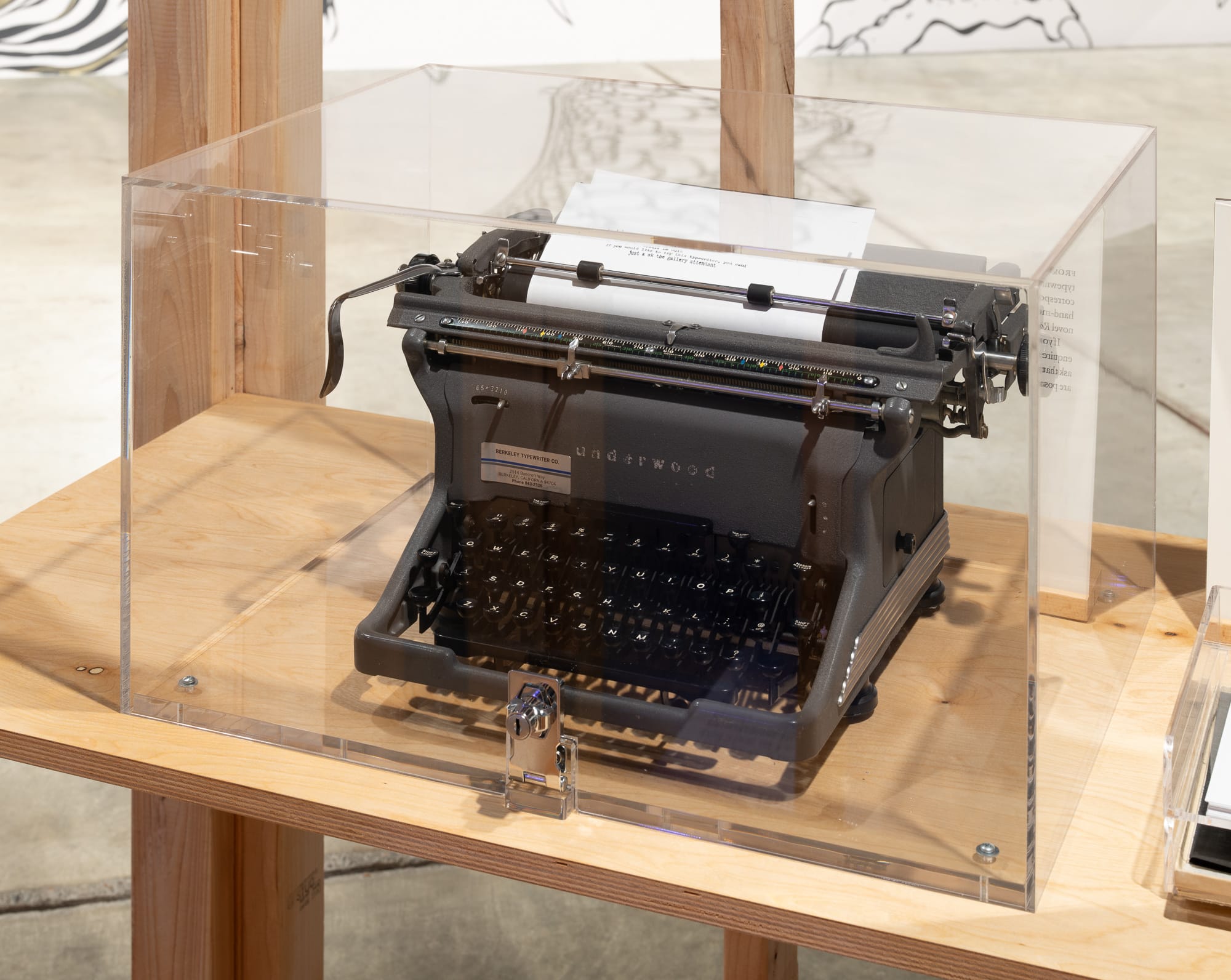

PORTLAND — Under an acrylic case in an exhibition I curated about my mother, the writer Ursula K. Le Guin (1929–2018), sits the first typewriter she purchased. Compact and impossibly heavy, the machine comes from an era of word production so distant as to feel alien. The keyboard has no exclamation point. To create the favorite punctuation of tyrants and optimists, one must type an apostrophe, then backspace and type a period.

The Underwood waited in my parents’ attic for decades as Ursula and the world moved on to electronic typewriters and eventually to computers. I hoped visitors to A Larger Reality, at Oregon Contemporary through February 8, could experience a little of the residual magic that I find clings to it, pecking out whatever they please, taking home the original and leaving a carbon copy for posterity.

I’m happiest when the case is removed and the gallery is filled with the sound of metal meeting paper. Visitors who’ve never used a manual typewriter, or who don’t touch type, peck tentatively. Others engage physically, producing the familiar percussive clack-clack sound of my childhood. Either way, I feel I’m sharing not just a machine but a sacred trust with strangers who love my mother’s writing and words in general.

People type poetry, memoir, fiction, epistles, articles, political statements, and fan mail on the Underwood. Some offer short tributes to Ursula or variations on “I can’t believe I’m typing on Ursula K. Le Guin’s typewriter.” Others compose prose or poetry on the spot. A few write nothing, go home to draft several pages, and return later to type something polished.

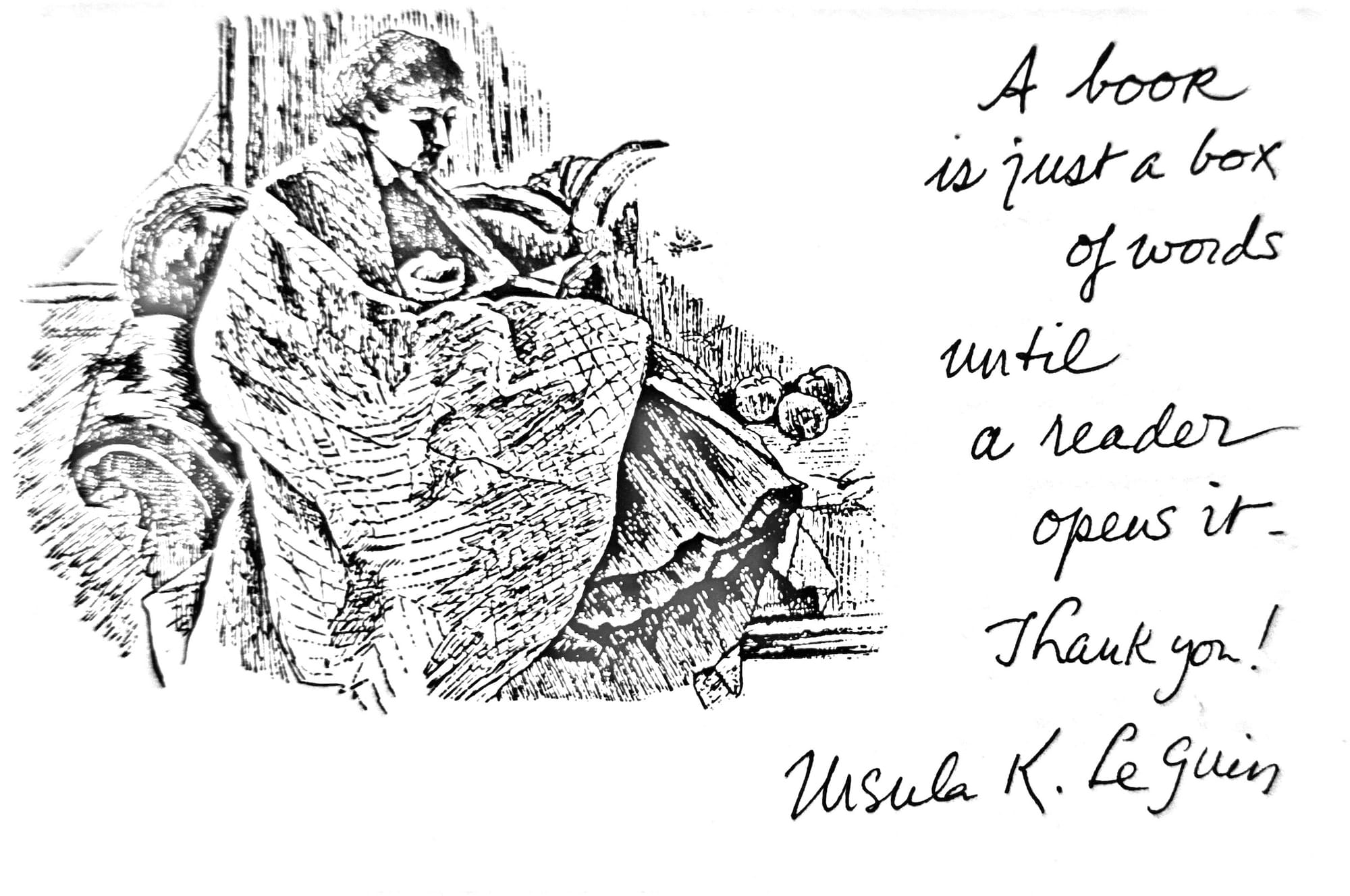

One visitor’s letter wondered how Ursula would feel knowing that her writing and cultural presence are no longer her own after death. The question is apt for me as curator and literary executor. Even a very private writer, while she is alive, exercises a restraining influence on people’s ability to misinterpret her words or life story. I can take comfort in my mother’s respect for the agency and necessity of readers in creating literature. For many years, her stock fan mail reply was a thank-you note, in her handwriting, acknowledging that “a book is just a box of words until a reader opens it.”

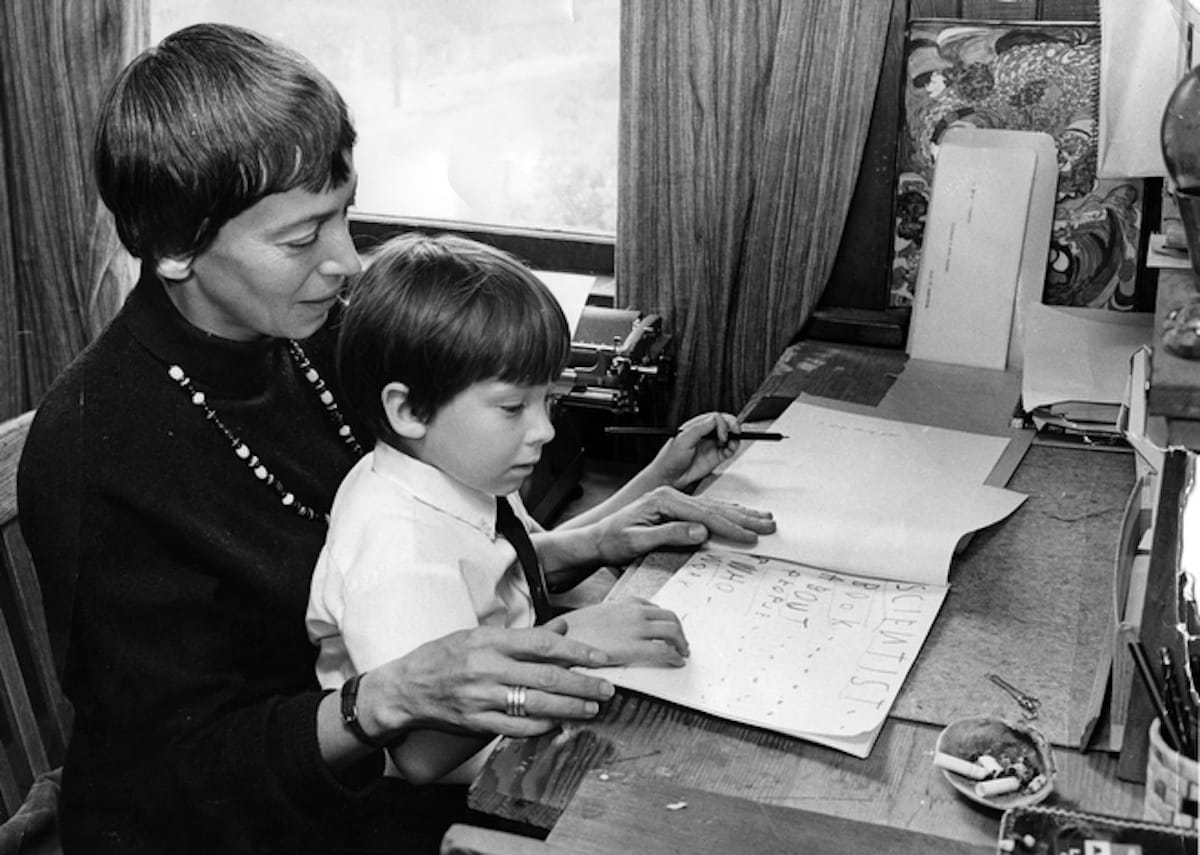

Over the past year, I’ve experienced cycles of grief and joy as I pored over my mother’s letters, manuscripts, and drawings to exhibit. I listened to hours of her voice, recreated an oak tree from her childhood and the room she wrote in from my childhood home. Curating an exhibition about your parent is a strange experience. Many visitors intuit this; the most common question I’m asked about the exhibition is what my mother would think about it.

Honestly, I have no idea. I’ve learned not to second-guess my decisions by constantly asking myself, “What would Ursula do?” I would never have proposed this exhibition in her lifetime, for fear that she might see it as reductionist. This is, after all, a writer who said in an interview, “Don’t shove me into your damn pigeonhole, where I don’t fit, because I’m all over. My tentacles are coming out of the pigeonhole in all directions.” Biographical and retrospective exhibitions exist in large part to assert and codify who an artist is. That is, at some level, a type of pigeon-holing.

This icon-production takes various forms, from hagiography to “objective” centrism to critique. True, if anyone is going to codify my mother, I prefer it to be me. I’m granted an advantage due to proximity and memory. But my version of Ursula is just one version. Even her version of herself was not authoritative. My mother remade herself, through her art, constantly and over decades. She revised everything from her early centering of male characters, to her use of he/him as the default pronoun in an imagined ambisexual world, to her critique of a Kazuo Ishiguro novel. Rather than worship an immutable icon, we should aspire to her willingness to learn and change.

From a technical, curatorial perspective, however, the mandate of narrative was my greatest hindrance. We’ve had it drummed into us that humans learn through stories, so anyone in an educative role must tell a story. For biographical exhibitions, however, linearity flattens the subject and condescends to the audience. I would go so far as to say this may be true for linearity imposed on any kind of exhibition.

My mother had something useful to say on this subject. Her essay The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction (1986), long a touchstone for writers, has recently become one for curators as well. Ursula posits, to simplify, that the reduction of narrative to linear, techno-heroic stories of conflict and conquest doesn’t serve us well. The hero’s journey remains a default model for storytelling in our culture, including for exhibitions. Ursula argues that the carrier bag, a humble yet capacious tool for gathering, is a better model for storytelling.

Exhibitions can be superb carrier bags for culture and knowledge. Few experiences offer so many chances for discursion and recursion, negative space and introspection. A carrier bag can expand to make room for the needs of the moment, for participation, spectacle, and immersion. In a carrier bag, none of these qualities, in balance, is antithetical.

For my part, releasing myself from the need to tell a tidy story about my mother led to an exhibition that is wordy, baggy, and inconclusive — but also, I believe, engaging and true to the subject.