Eugène Atget, Readymade Icon

An exhibition retells the story of his discovery by Berenice Abbott, leaving out the details of a life defined by failure.

It wouldn’t be wrong to say that Eugène Atget, one of photography’s major figures for almost a century now, is in danger of seeming old hat. So when the International Center of Photography promised “a new approach to the story of Atget’s career” with its exhibition Eugène Atget: The Making of a Reputation, I took the bait. (What exciting new revelations might lie in store?) Alas, that line turned out to be a bit of PR propaganda. The exhibition rehashes the now-familiar story of how Atget would have languished in obscurity if it weren’t for the photographer Berenice Abbott, who rescued his archive after his death, printing and promoting his lonesome images of Parisian streets. Indeed, the most novel feature of ICP’s approach may be the exhibition’s color scheme: dark red walls and shiny gold text — atmospheric, yes; legible, maybe — which are perhaps a nod to the grand galleries of yore.

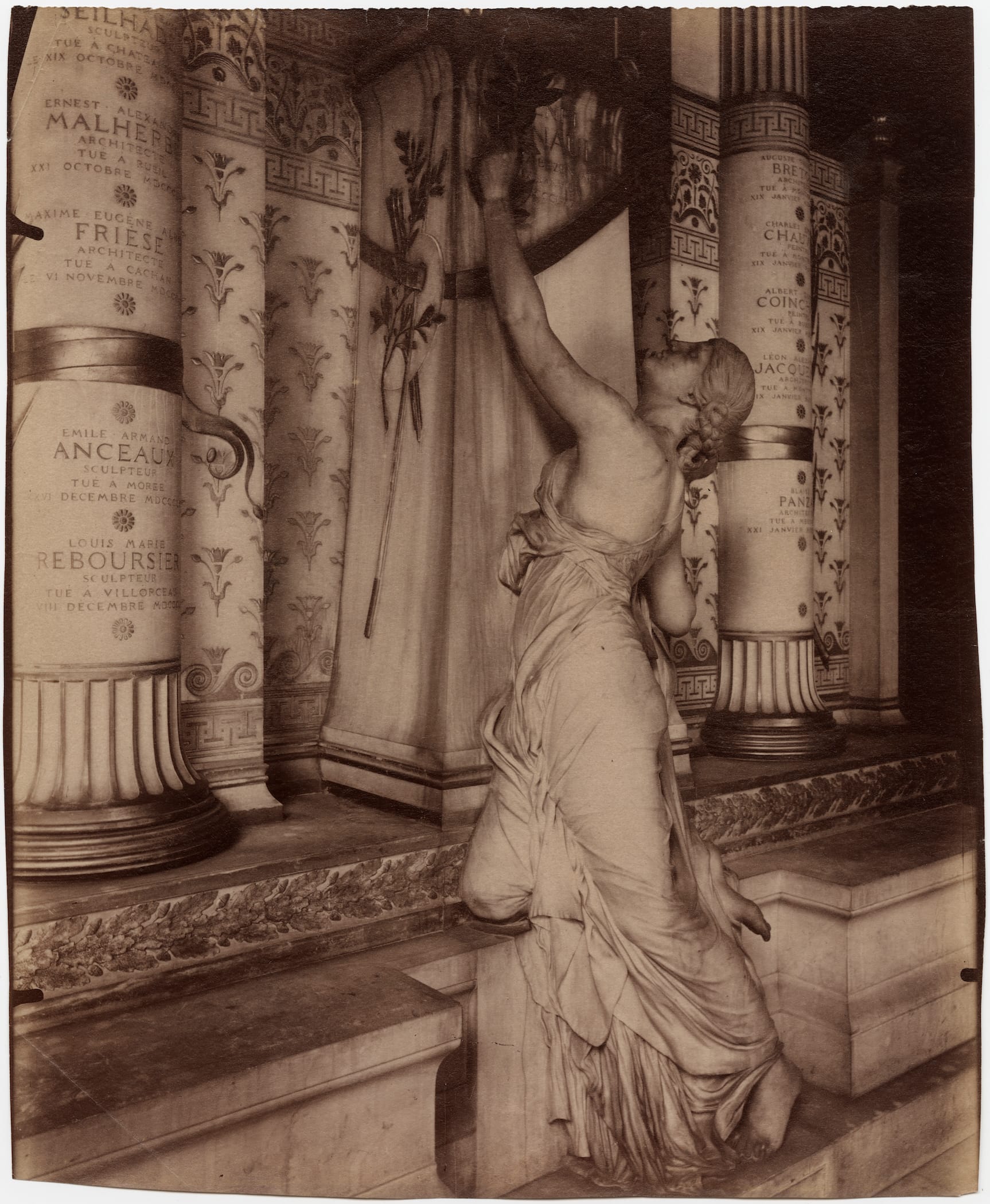

Likewise, while the exhibition is called The Making of a Reputation, Atget’s prestige is presented to the viewer as ready-made. The show doesn’t include much expository text (not necessarily a bad thing), but its walls are sprinkled from the beginning with the shining accolades of the photographer’s peers. We hear that Atget was “an artist, strong and courageous,” someone who “reached the pole of utmost mastery” and was “the most important forerunner of the whole modern photographic art.” (That the show’s glowing anecdotes are literally delivered in gold really drives the point home.) These words make it harder to imagine the Atget whose life was defined by failure, the orphan who worked as a cabin boy before struggling to make a career as an actor, the unsuccessful painter who turned to photography in his mid-30s to earn a living — how contingent and not at all foreseeable his posthumous fame was.

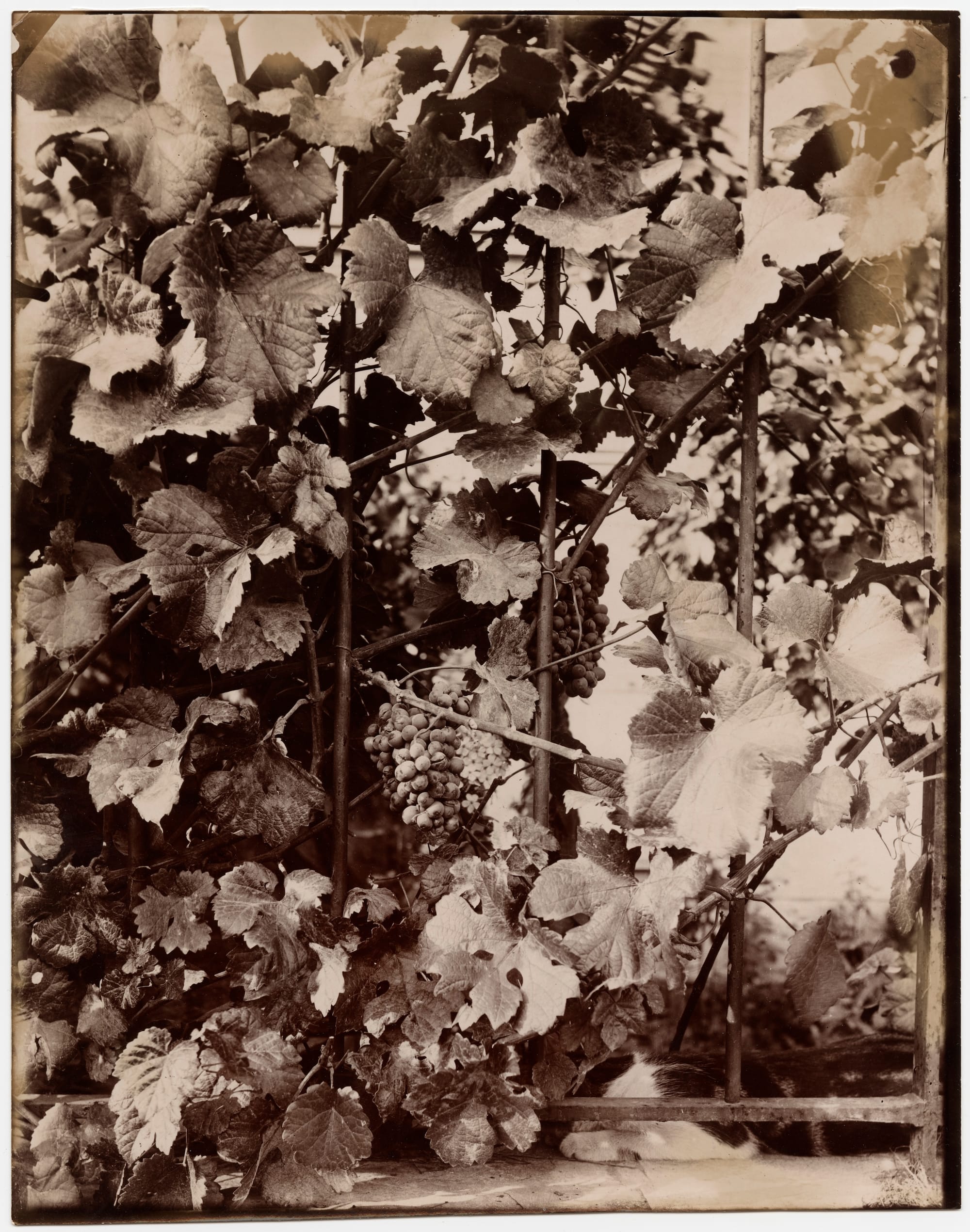

Nevertheless, despite the show’s false pretenses, I was glad to have been lured there. Many of the prints are stunningly gorgeous, revealing depths so detailed — and inviting you to lean so far forward — that you almost want to fall into the photograph. You can count every leaf on a bush, every post on a sloping wooden fence. Peering at a seven-by-nine-inch (~18 x 23 cm) photograph like “Pontoise, Place du Grand Martroy” (1902), one gets the same sort of pleasure as when looking at a miniature diorama: that simultaneous yearning for the unreachable and delight in its tininess. (Viewers with foresight will smuggle in a magnifying glass.)

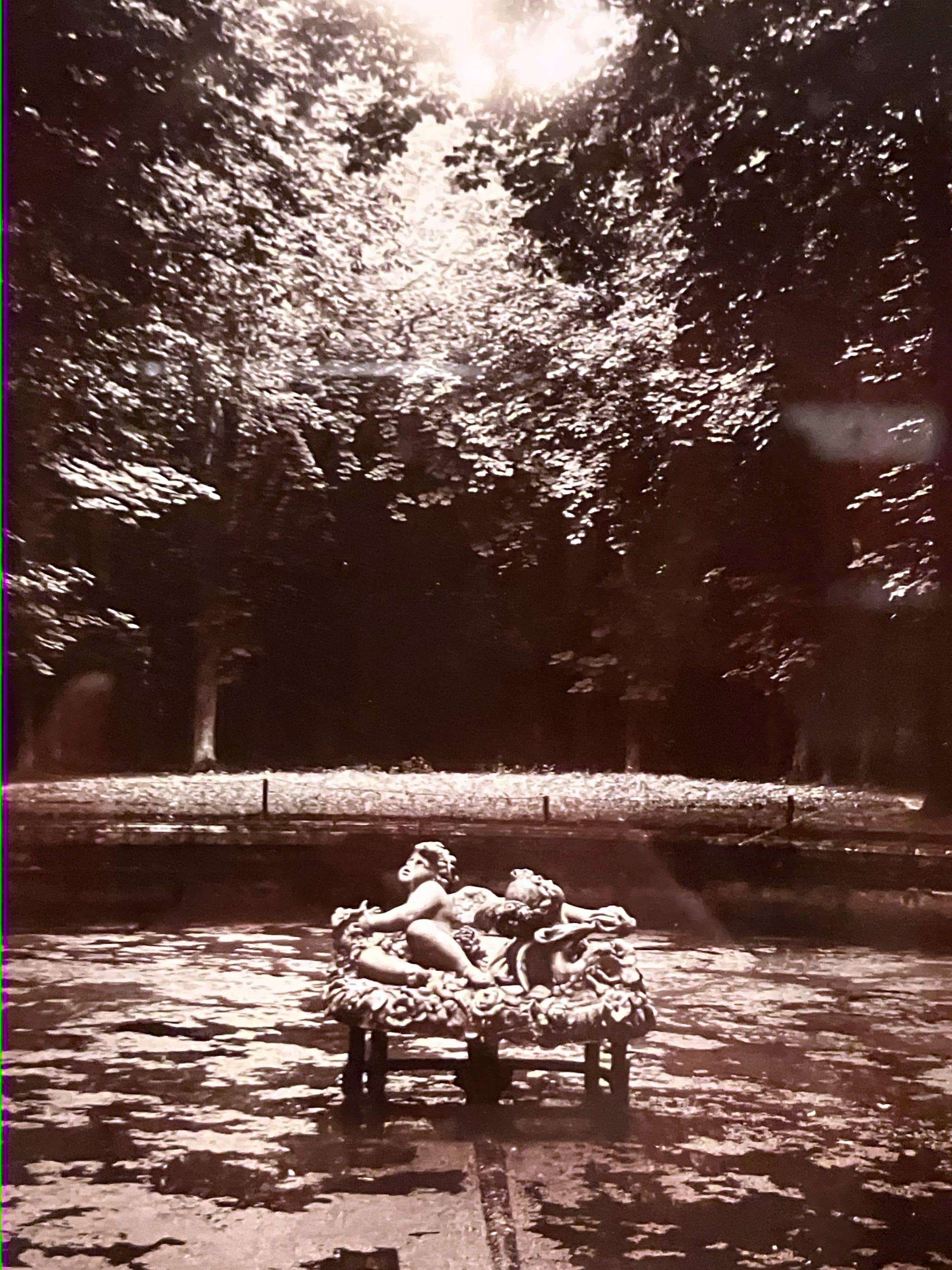

Atget sought to collect the disappearing world of old Paris in his images, a city that was cluttered and a little ramshackle, almost Dickensian in its accumulation of things. He photographed at the crack of dawn, before people were out on the streets, and their absence is hauntingly present: Are they the ghosts of this world, or are we? “Trianon” (1926), shot in a moody garden, shimmers with exactly this kind of resonance; our eyes travel past the sun-dappled fountain and towards the field beyond, pulled into pastures deep enough for one’s imagination to take up residence. It’s the kind of scene that lodges itself in the back of your mind, returning in dreams or as ambient half-memories of places you might have been to, or never visited at all. That’s probably why the Surrealists loved him so much.

Atget himself never thought of his photographs as art, though, nor did he seek recognition for them. Rather, he marketed and sold his careful records of old Paris as “documents for artists,” visual references for painters looking to recreate things like a wrought iron banister or an arched doorway. After meeting Atget, falling in love with his work, and later managing his estate, Berenice Abbott — who was then frequenting Surrealist circles — posthumously rebranded the photographer as an artist. (The academic debate over how to contend with this tricky move goes back to at least the ’80s.) It’s therefore particularly evocative seeing portraits of the two hanging side by side in the show: Both look pensive, a little rumpled, and piercing in their own ways. There’s a generational divide in how the photographs are composed, with Atget posing as the classic head-on subject while Abbott lies down at a modernist angle, a cat tucked snugly in the crook of her elbow.

This collision of two different worlds seems present from their first encounter. Today, it’s impossible to know whether the frisson of Atget’s photographs comes from Atget himself, or from Abbott’s appropriation of his archive. Is the awe that the photographs inspire due to their odd dislocation from their original context, something akin to Marcel Duchamp hanging a shovel from the ceiling? Could someone in 2026 take the oeuvre of an early 2000s stock photographer and turn it into a contemporary masterpiece, precisely because of the alienation we feel from their world? These questions matter as images become easier to recycle and repurpose. Walking out of the show, the “newness” of ICP’s approach to Atget no longer seemed to matter; who needs an excuse to revisit such things?

Eugène Atget: The Making of a Reputation at the International Center of Photography (84 Ludlow Street, Lower East Side, Manhattan) through May 4. The exhibition was curated by David Campany.