Extinct Feathers Flock Together at Smithsonian

Once ubiquitous in North America, by 1914 the population of passenger pigeons had been reduced by relentless hunting to a single bird named Martha at the Cincinnati Zoo. When Martha herself was found dead in her cage on September 1 of that year, she was packed on 300 pounds of ice and rushed to the

Once ubiquitous in North America, by 1914 the population of passenger pigeons had been reduced by relentless hunting to a single bird named Martha at the Cincinnati Zoo. When Martha herself was found dead in her cage on September 1 of that year, she was packed on 300 pounds of ice and rushed to the Smithsonian Institution for preservation.

Her small taxidermied form and bits of bone are among other relics of disappeared birds in Once There Were Billions: Vanished Birds of North America. The exhibition, which opened last month at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History (and was co-curated by the Biodiversity Heritage Library and Smithsonian Libraries), recalls our lost natural heritage on the centennial of Martha’s death.

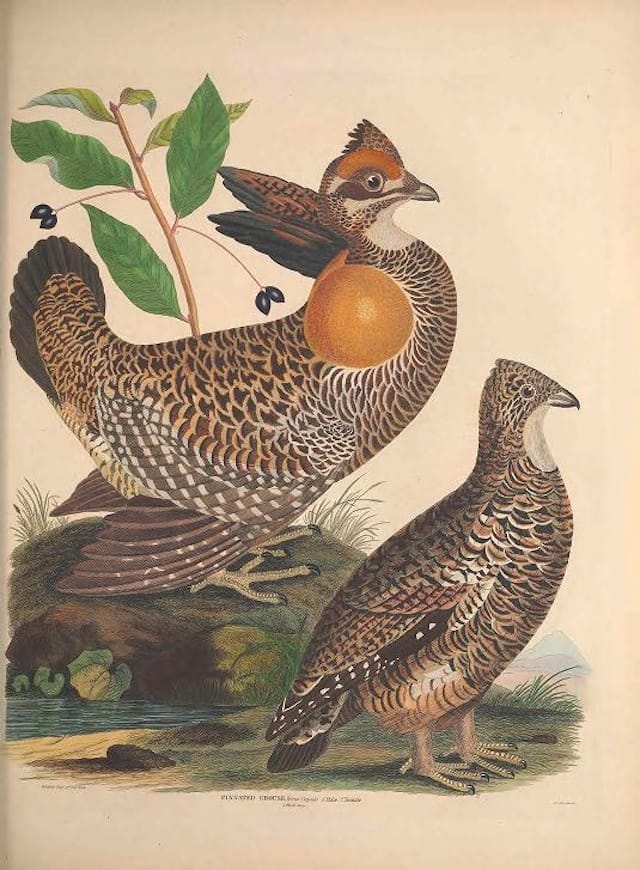

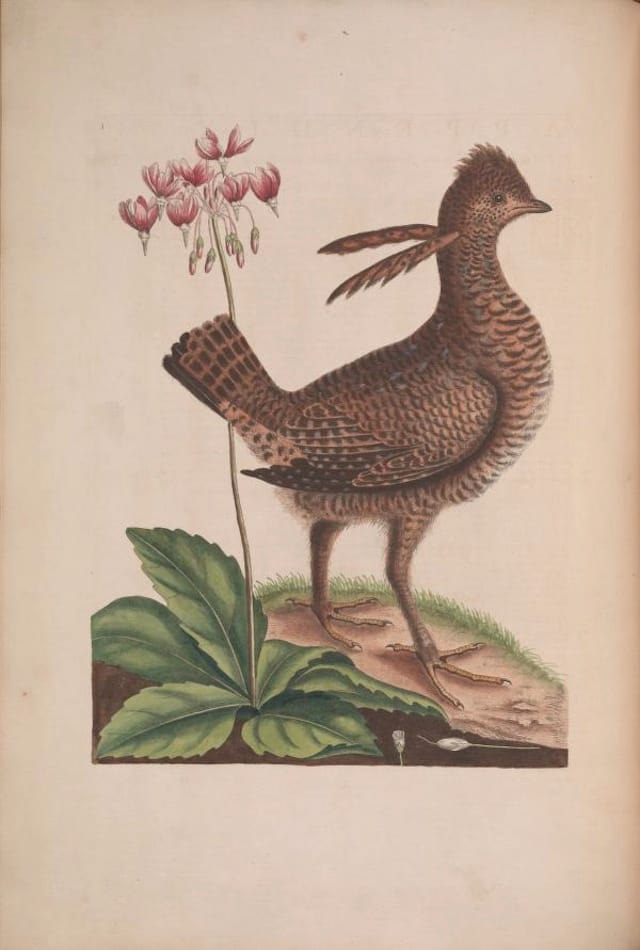

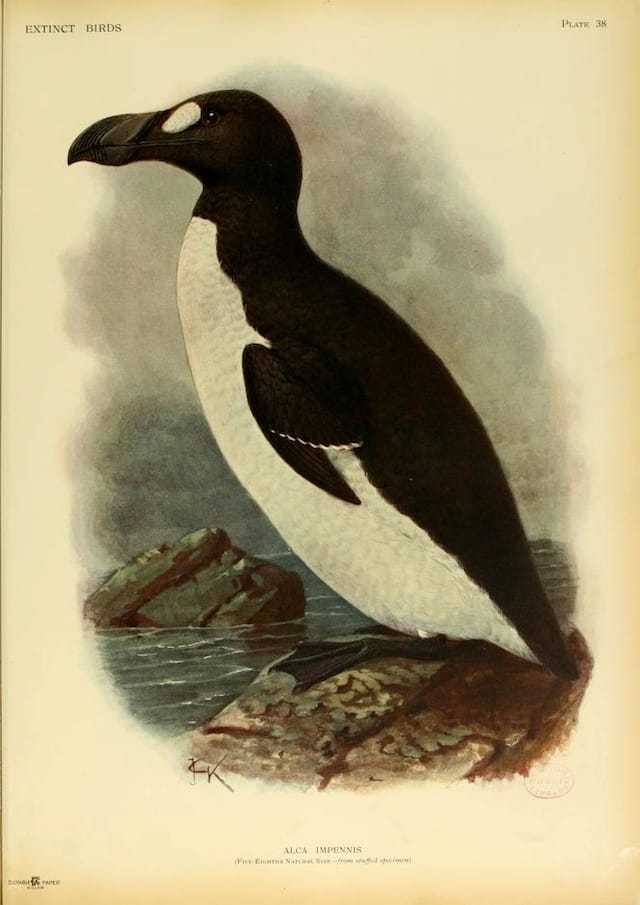

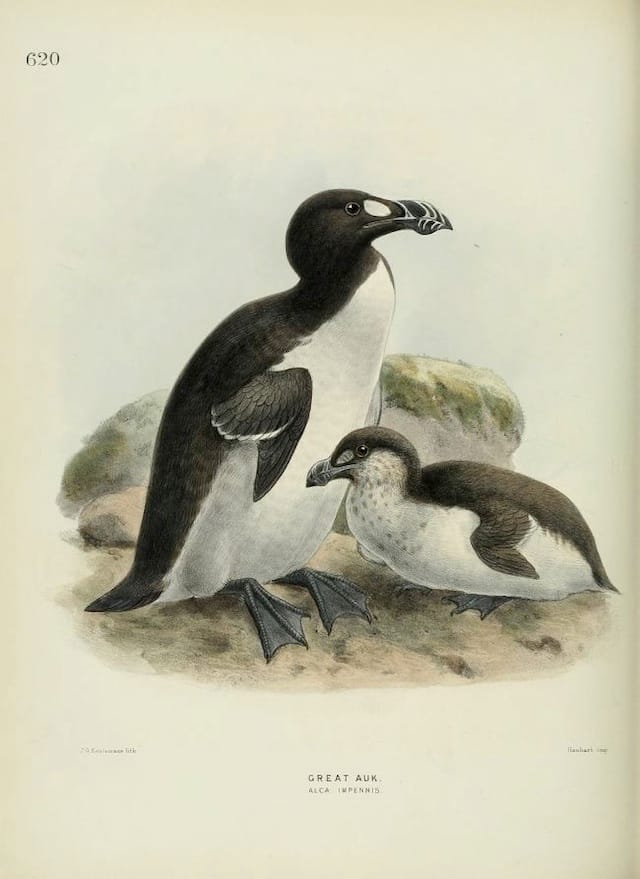

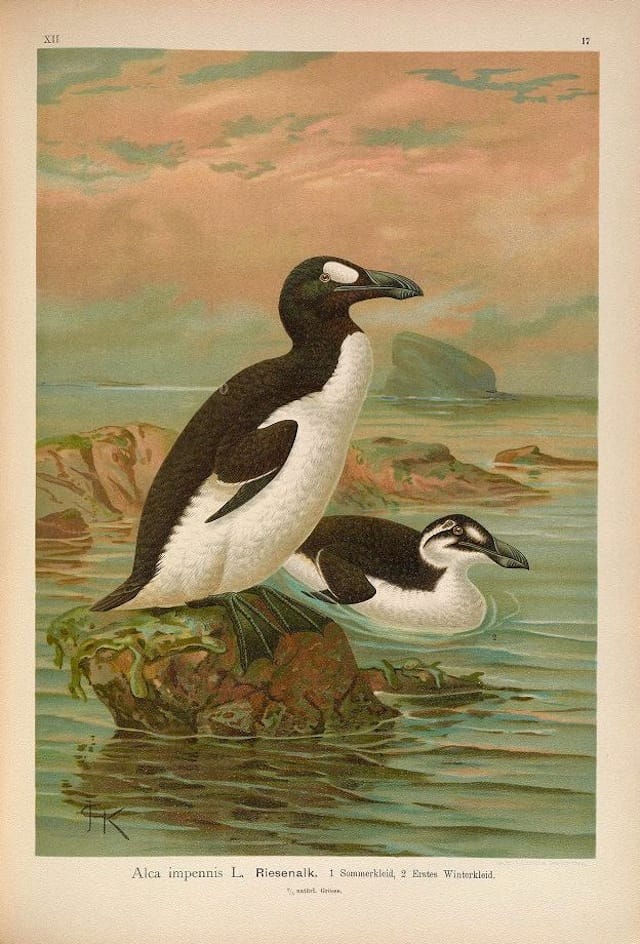

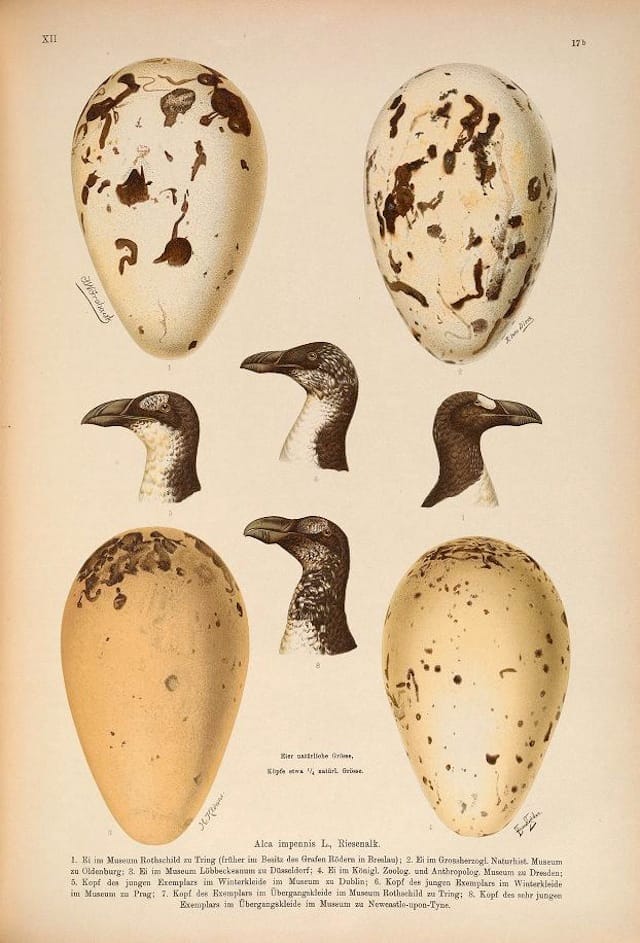

Along with the passenger pigeon there was the great auk, extinct by the 1850s, an extraordinary swimmer related to the puffin whose awkwardness onshore made it an easy victim of hunting; the heath hen, extinct in 1932, preyed on by hunters and feral cats; and the brilliantly colored Carolina Parakeet, a rare cold-weather species of parakeet whose beautiful plumage drove hunting until its extinction in 1918. What’s left are preserved specimens frozen with glassy eyes, skeletons, and illustrations. Some naturalists, cognizant of the perils faced, recorded these birds when they were alive, while others, like John James Audubon, worked from dead specimens.

While all stories of extinction are harrowing, the passenger pigeon’s demise was of an almost unbelievable scale. The species once made up 40 percent of all the land birds in North America, soaring at 60 miles per hour. John James Audubon wrote of seeing a flock on his way to Louisville in 1813: “the air was literally filled with pigeons; the light of noon-day was obscured as by an eclipse.” Jerry Sullivan in his 1986 essay “The Passenger Pigeon: Once There Were Billions” stated: “Where ever they went, they must have hit like the plague,” with a nesting colony taking over 50 square miles, as many as 500 birds in a single tree. But, he continues, “[a]s many as a thousand men worked as professional pigeon hunters in the late 19th century.” Soon the dead birds were being packed in barrels of 500 to 600 birds each, their flocks dwindling rapidly. “A passenger pigeon was too stressed to function unless it had millions of its fellows right in its face,” Sullivan writes. “And so the passenger pigeon passed.”

There’s been recent interest in bringing back the passenger pigeon, but no matter what DNA-based resurrection is possible, the species will never again come to dominate the skies of North America. Alongside Martha’s centenary commemoration, there are also projects such as the adorable Fold the Flock, which recreates the pigeon crowds through origami, and artist Todd McGrain’s “The Lost Bird Project,” an installation of large-scale bronzes of the passenger pigeon, Carolina parakeet, great auk, heath hen, and Labrador duck presented by the Smithsonian Libraries and Smithsonian Gardens. Online, you can swerve through a 360-degree view of Martha, and through the vivid illustrations that date back to the 18th century get a glimpse of this vanished biodiversity.

Once There Were Billions: Vanished Birds of North America continues at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History (10th Street & Constitution Avenue NW, Washington, DC) through October 2015.