Five Venezuelan Artists Respond to US Attacks

Artists and art workers in the diaspora shared a mix of emotions, from hope of a better future to anger over the unsanctioned intervention and fear of what’s to come.

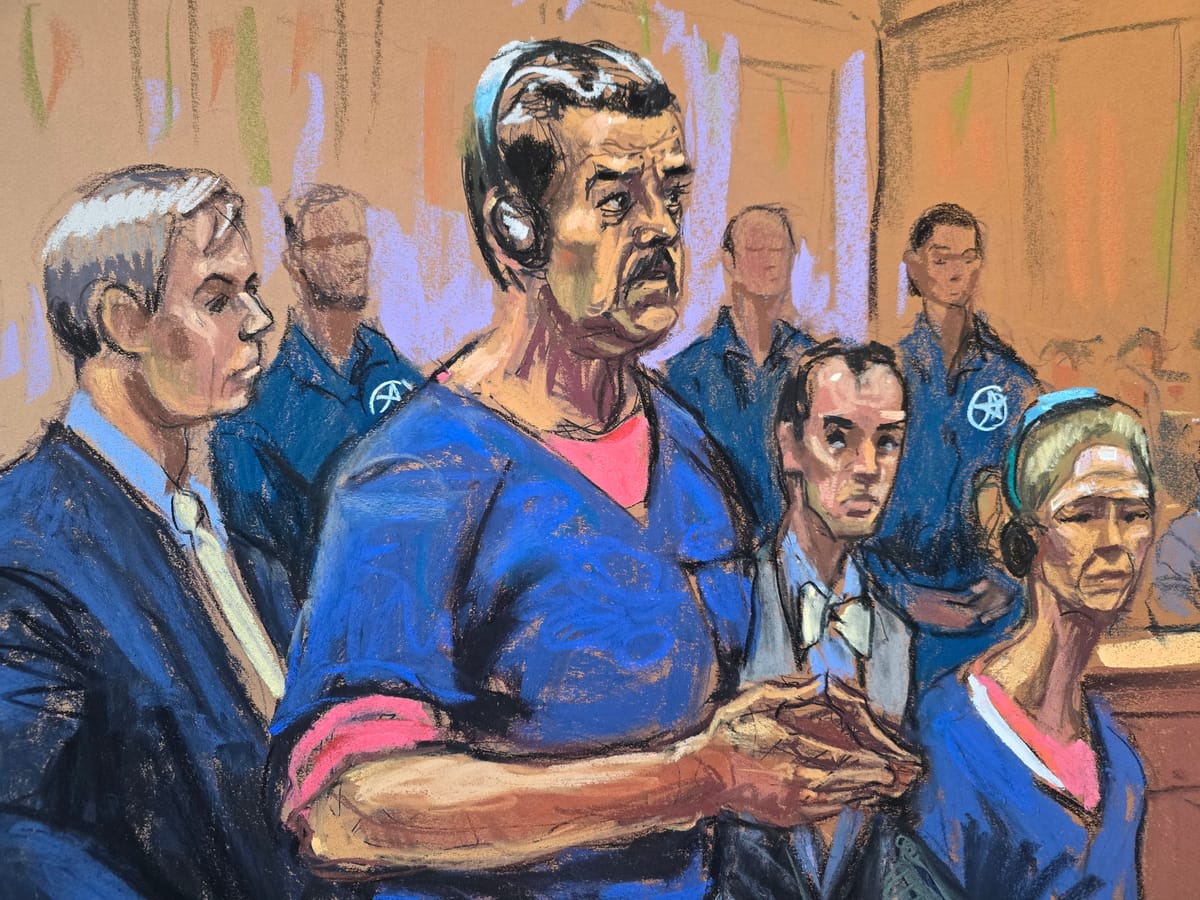

In the early hours of Saturday, January 3, the United States military carried out a raid and bombardment in Caracas, Venezuela, and abducted President Nicolás Maduro and his wife, Cilia Flores. The assault in the capital city, which killed at least 40 people including civilians, according to local authorities, stunned and divided the world. As many celebrated what they saw as the downfall of a tyrant, others condemned President Trump's stated intent to take Venezuela's natural resources. Still others saw in the strikes the long shadow of US intervention in Latin America, often with deadly results.

Hyperallergic asked various artists and art workers in the diaspora for their honest, personal responses to this weekend's events. Texts from Javier Téllez, Jeffly Gabriela Molina, Vero Bello, Cassandra Mayela, and Silvia Benedetti — who witnessed the bombings firsthand in Caracas — are appended below. We continue to make efforts to reach artists in Venezuela, many of whom fear persecution if they speak publicly.

"Sovereignty must be respected"

“I believe it is regrettable that many Venezuelan artists are not condemning the military intervention of the USA in Venezuela, especially artists addressing geopolitical issues in their work and assuming postcolonial stances. I have actively participated in the opposition to Chavismo since 2003, when I resigned publicly to represent Venezuela in the Venice Biennale. I still oppose the regime but this does not mean I support any foreign intervention in the country, neither before nor in the future.

Venezuela as any other country's sovereignty must be respected. The military intervention of the USA in the country as well as Trump's threats should be outrageous regardless of one’s political stance. Maduro was a dictator, there should not be any doubt about it, and his hench people are illegitimately still in power. The main question here is who should have the authority to remove them. Neither Trump or any other foreign agent does. An invasion of the USA would be a profoundly tragic event for our country and the continent. It seems we haven’t learned how lethal all US military interventions have been, from Vietnam to Iraq and Afghanistan.

The worst thing that could happen to Venezuela is a war. It is unthinkable that the country that in 1958 shouted to Nixon for the first time ‘Yankees go home’ will now welcome American troops, or that a country that fully nationalizes the extraction of oil fifty years ago is going to give fully its natural resources to the USA. Let’s not forget that Venezuela gave birth to Simón Bolivar, who led Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Panama, Peru, and Venezuela to independence from the Spanish Empire more than two centuries ago.”

— Javier Téllez, New York City-based artist from Valencia, Venezuela

"A mix of hope, frustration, and fear"

“I moved to the United States at 17, and I am 36 years old now. For years, a powerful faction of the military has backed Maduro and Chávez, and Venezuela has effectively become a military dictatorship. Many Venezuelan political prisoners have been tortured or disappeared, and more than eight million Venezuelans, about a third of the population, have fled the country. Before Chávez, US companies partnered with our oil industry, and Venezuela was prosperous. Chávez damaged those relationships and aligned instead with Cuba, Russia, China, and Iran — alliances that helped protect the regime while the economy collapsed. So when people say the US is intervening to take our oil or minerals, many of us respond: ‘And what did you think the Chinese and Russians wanted? The arepa recipe?’ (This quote comes from a Venezuelan man in a widely shared video that became viral precisely because it resonates with how many of us feel about people suddenly questioning where some of our oil and resources might go.)

For many Venezuelans, Maduro’s arrest brought real hope after decades of abuse. Maduro is a criminal, and yesterday felt like a very good day for us.

However, the immense joy many of us had anticipated, even daydreamed about, was deeply overshadowed by Trump’s comments about ‘running’ our country and his disparagement of opposition leader María Corina Machado. Many of us were aghast. I even thought: How could he discredit himself so terribly? Without the movement and leadership of the Venezuelan opposition — the very force that exposed the regime’s crimes — the actions of his administration against Maduro would have little justification.

We have strong, chosen leaders who can and will return to Venezuela. María Corina, who won international recognition after leading the opposition’s landslide victory in the 2024 presidential campaign — supported by transparent results and citizen participation — is set to assume the role of vice president, while Edmundo González was chosen as our president. My own father committed his time and safety to be a voting witness in that election.

My perspective on the legality of the extradition is that this government did what needed to be done. Perhaps we need clearer international mechanisms so governments do not debate indefinitely whether to act against regimes that endanger their people or cause mass displacement. Look at what’s happening in Gaza; how wonderful it would be if a powerful nation would cut through political gridlock, ignore vetoes, and stop genocide once and for all. Look at what President Obama did with Bin Laden — that operation did not go through Congress.

Seeing how some of my liberal friends are reacting to Maduro’s extradition, I’m relieved Trump did not seek congressional approval. Maduro is a terrorist — one responsible for the imprisonment, torture, deaths, and disappearance of thousands.

But alas, Trump too shows signs of despotism. So what do we do? How am I supposed to feel? My emotions are a mix of hope, frustration, and fear.”

— Jeffly Gabriela Molina, Chicago-based artist from Táchira, Venezuela

"We could hear planes flying overhead"

“I have been living and working in New York since 2012, while spending significant time in Venezuela, where my family lives and where I maintain my professional practice. Having studied journalism in Venezuela, I witnessed the rise of state censorship firsthand — from the implementation of the ‘Gag Law’ to the forced closure of RCTV. More recently, while working on my Andy Warhol Foundation grant project that had nothing to do with politics, my team had to be evacuated for security reasons. This was due to the intense persecution of the international press that followed the 2024 presidential election.

I am in Caracas. On January 3, around 2:00 am, I witnessed explosions at Fuerte Tiuna — the military complex where Maduro was captured. The windows and walls of my home were shaking. We could hear planes flying overhead, though they remained invisible to us. At that moment, we had no idea what was happening. We began receiving frantic calls from family and friends across the city; everyone was terrified.

I am deeply concerned about my country. The priority is the restoration of sovereignty, democracy, and peace, as well as the release of political prisoners. As long as this doesn't change, those who suffer — and will continue to suffer — are the poor, due to the extremely grave economic situation.

I am concerned that we, as Venezuelans, have a short memory and fail to see how history repeats itself. I am deeply grateful to my international friends for asking questions and offering their own perspectives. For those seeking a deeper understanding of the current situation, I highly recommend reading Boris Muñoz’s recent analysis published in El País.

I am struck by how local artists and curators continue to engage with national museums, which serve as communication channels for the regime and are known for blatant censorship. A clear example is the Creadoras project at the National Art Gallery and exhibitions at Museo Alejandro Otero. While some participants may be naive, others seem driven by a desperate desire for visibility at any cost. Participating in these institutions is an act of collaboration with the regime, not a form of resistance.

Paradoxically, some of these same individuals also support a US invasion. It saddens me to see such a profound lack of critical thinking and genuine conviction.”

— Silvia Benedetti, Venezuelan art historian, curator, and critic based in New York

"Venezuela has been 'invaded' since I was born"

“I was born in Caracas in 1998, the year Chávez won the election. My family is from very humble beginnings. My dad was born in La Pastora, one of the bombed sites close to a military base. My mom is the daughter of immigrants from the Canary Islands. In Spain they were farmers, and they came to Caracas in the 1950s escaping the Franco regime.

Despite their humble beginnings, my parents grew up in a Venezuela where upward mobility still existed. Little by little, my mom and dad experienced a comfortable young adulthood and eventually a very prosperous adulthood. In 2003, the country started experiencing a rise in violence. My dad received a job offer in Mexico City and my nuclear family relocated. Every year we continued going back to Caracas for summer and Christmas vacations. Our entire family was still there at this point, and as a kid I was experiencing the country from afar, constantly hearing about violence and injustices. I started perceiving my birth country as a scary place.

In 2010, Venezuela experienced a huge surge in violence. The media began to be censored and fear became prevalent in people’s lives. My uncle gave a large donation to the opposition against chavismo, and it became dangerous for my family to stay in Venezuela. This pushed my family to move the business to South Florida. I ended up growing up in the US, going to public school in Miami and then art school in Rhode Island. The family business eventually crashed in 2017, one of the hardest years for people in Venezuela with week-long electricity blackouts and mass kidnappings. My family went bankrupt right before the pandemic and continues to struggle financially to this day.

I became a citizen in 2020 and I am a registered Democrat. I care about human rights. I feel disgusted by the Israeli government’s actions and US involvement in the genocide. I am for a free Palestine. I recognize the evils of capitalism, and I am anxious about the state of the world as I observe my generation and members of my own family leaning more and more toward far-right politics.

I also think it is important to say that I recognize chavismo did not come out of the blue and that Venezuela is an extremely classist and racist society. The Venezuela my parents lived in and prospered in was far from perfect.

I absolutely despise Donald Trump and I do not trust anyone in his abhorrent administration. At this point I feel almost the same about the Democratic Party. If I look at this intervention strictly through the lens of my American identity, I am against spending our tax dollars intervening in other countries. History has shown this does not benefit anybody involved.

On the other hand, looking at this through my Venezuelan lens, I could argue that Venezuela has been ‘invaded’ since I was born. It was invaded by an unjust regime that has killed civilians, separated millions of families, censored the media, kidnapped children, dissolved private businesses, including my family’s, and fully mismanaged the country’s resources, destroying both private and public institutions. They have done this under the guise of helping the poor, but Chávez and his administration are known for driving luxury cars, owning multiple homes internationally, and living very lavishly.

My distrust of Trump also tells me that many of his actions are performative. We are well aware that he wants oil, but it feels very patronizing when leftist American peers use this argument as the main reason not to intervene, while the reality is that Venezuelan oil has not belonged to Venezuelans for many years. If you were to ask most Venezuelans, they would immediately say this is a price they are willing to pay in order to end the regime.

Finally, and personally, I am mostly upset that this event will breed more and more ‘MAGAzuelans.’ I have several friends in Miami from other nationalities, like Colombian, Peruvian, and Argentinian, who strongly identify with the MAGA movement, which is extremely mind-bending as we watch horrific ICE raids across the country.

On a very selfish note, if this intervention means I can one day go back to Venezuela to truly get to know my home country through my own eyes and with my five senses, then I pray this moves quickly and that innocent civilians stop getting hurt.”

— Vero Bello, Venezuelan-born artist based in Brooklyn

"More honesty and solidarity, and less blind radicalism"

“I strive to live my life autonomously, valuing freedom of thought without aligning with any specific trend, group, or movement. Those who confine themselves to a particular trend risk losing perspective on other viewpoints and experiences. In my opinion, truth has a degree of subjectivity; even facts can be interpreted subjectively, as they depend on individual perception. The situation in Venezuela is not black and white or a binary dispute. Yet, as always, each side defends its own narrative while ignoring any flaws. In these narratives, it is the people who always suffer the most.

I have never adhered to slogans, and perhaps this is why I, like many other Venezuelans, am often misunderstood. It’s a challenging and uncomfortable position to express that ‘I don't identify with any specific group,’ because it's often interpreted as ‘If I'm not with you, then I'm against you.’ When the focus shifts to mineral resources rather than to the people who have endured torture and trauma for over 20 years, the conversation becomes one about property rather than humanity. I prioritize listening to the people. Listening, in Venezuela, means bursting your bubble, opening up your mind, and dismantling the frameworks that both the Left and Right rely on. I want to see more honesty and solidarity, and less blind radicalism. I want to see real liberation from every autocratic regime, government, empire, etc. I’ve often stated that my practice is a service to the people — to offer ways to process, heal generational wounds, and create spaces for sharing and building community. That’s the only commitment I have.”

— Cassandra Mayela, Caracas-born artist based in Brooklyn