From Dürer to Ensor, a Collection of Prints Gives Us Grim Reminders of Death

The 54 lots in this Christie's online auction span from the 15th to the 20th century and demonstrate an array of European attitudes towards death.

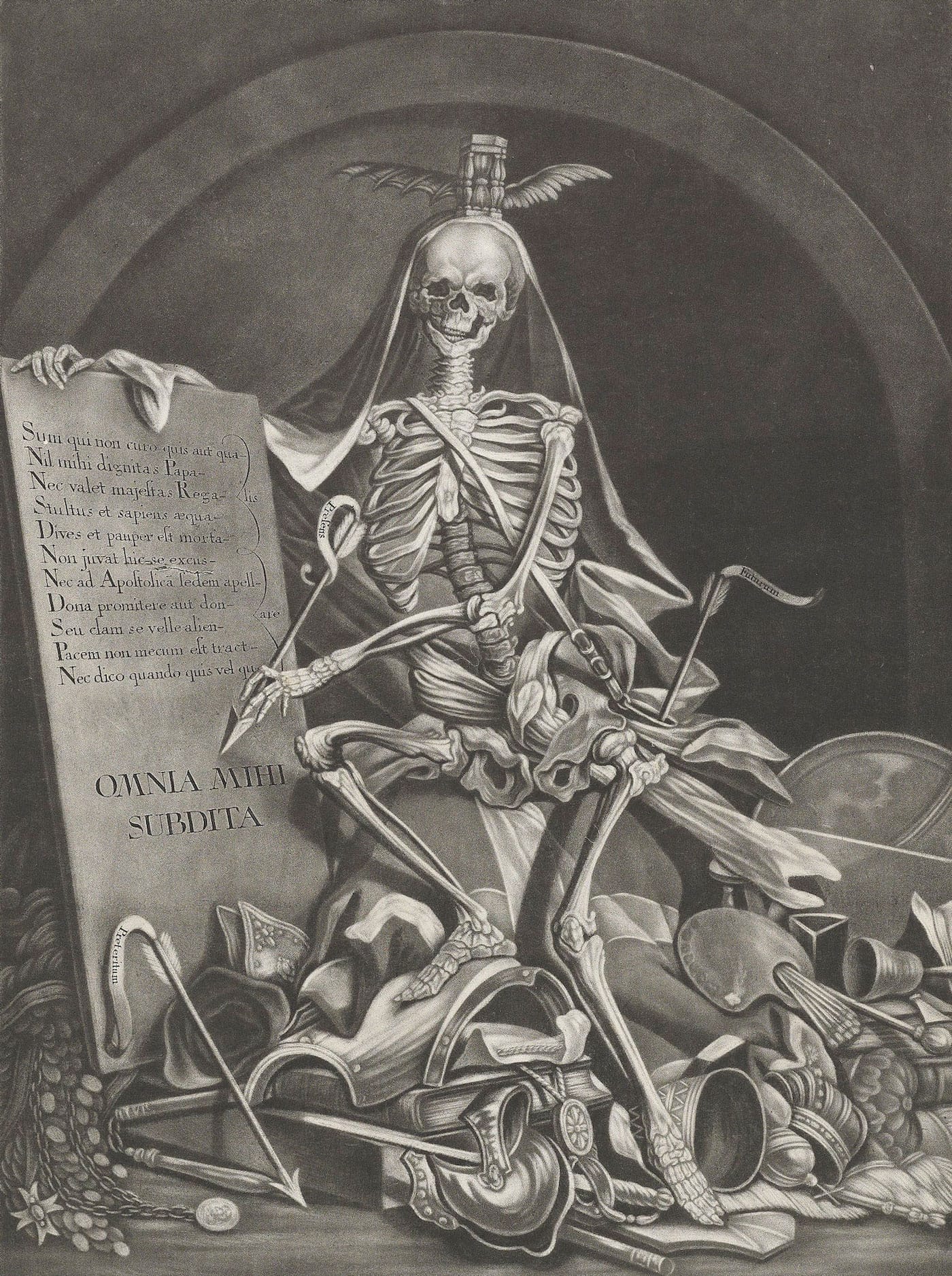

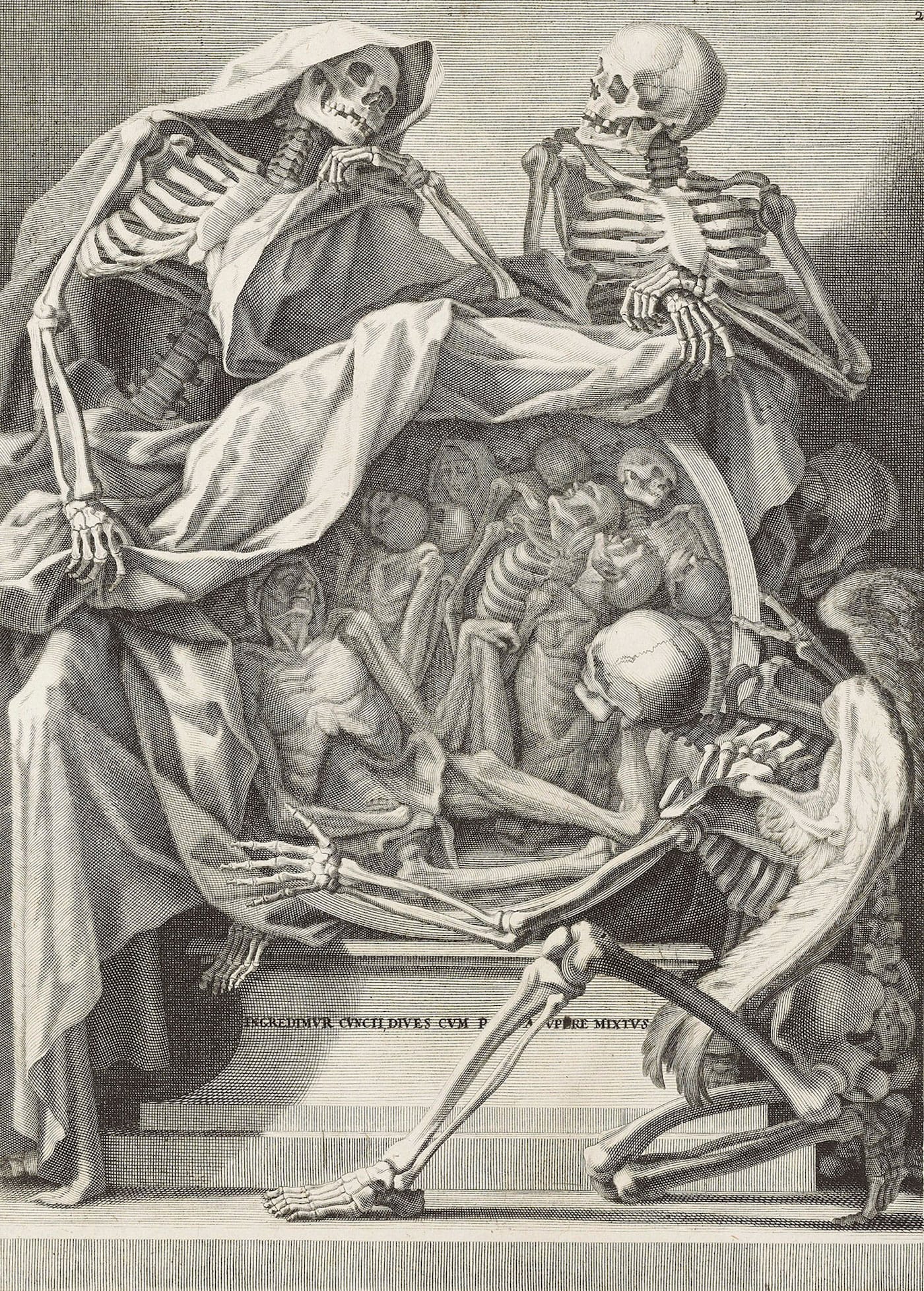

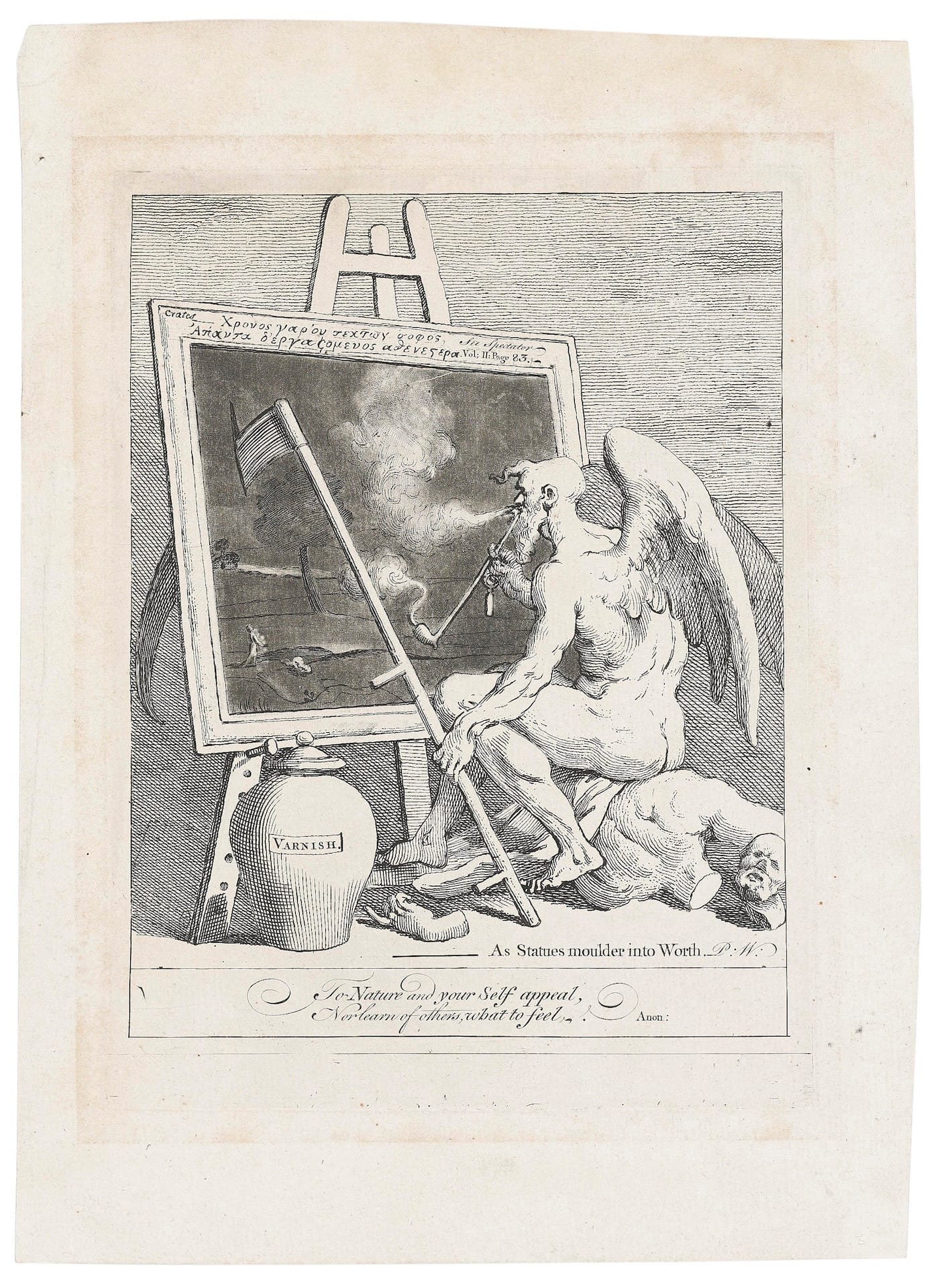

“EVERYTHING SUCCUMBS TO ME.” So reads the text — in Latin — on a tablet that the leering skeleton in an 18th-century mezzotint print points to with his arrow. Rendered by the German engraver Johann Jacob Ridinger, the image is chilling. The boney figure sits comfortably atop a mound formed by weapons, an imperial crown, a painter’s palette, books, and coins. The message is clear: no one — not men of might, power, creativity, intellect, or wealth — escapes death’s grip.

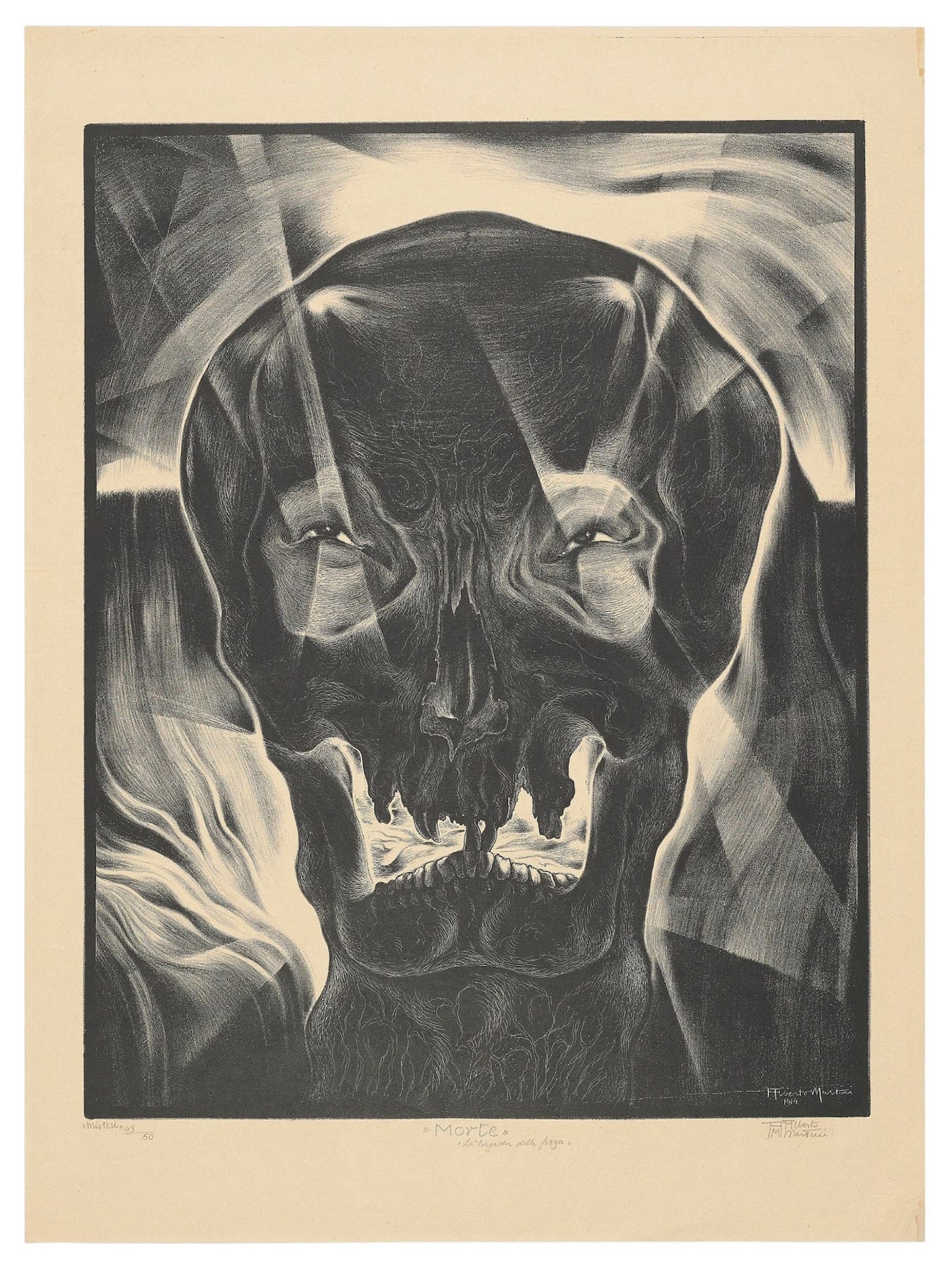

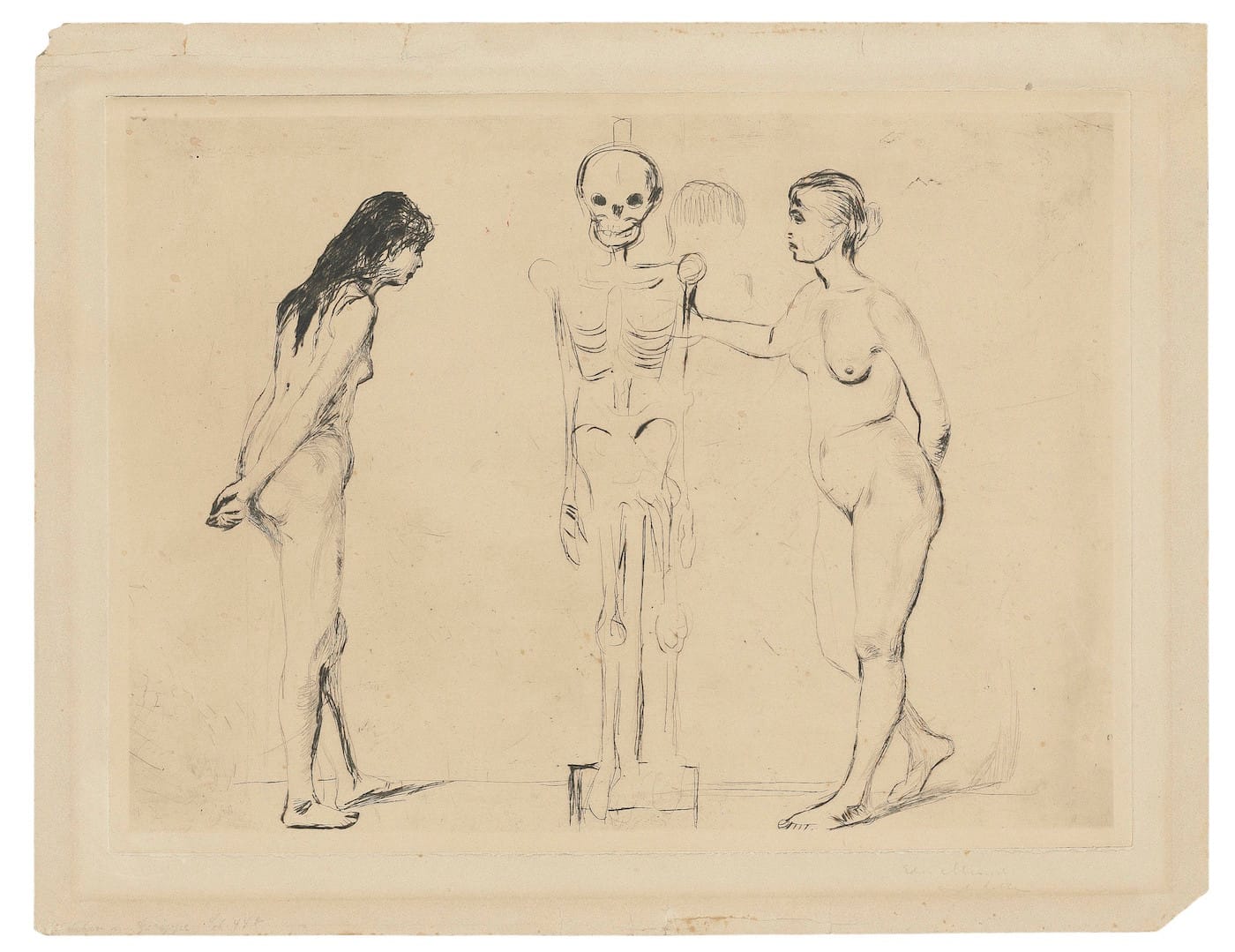

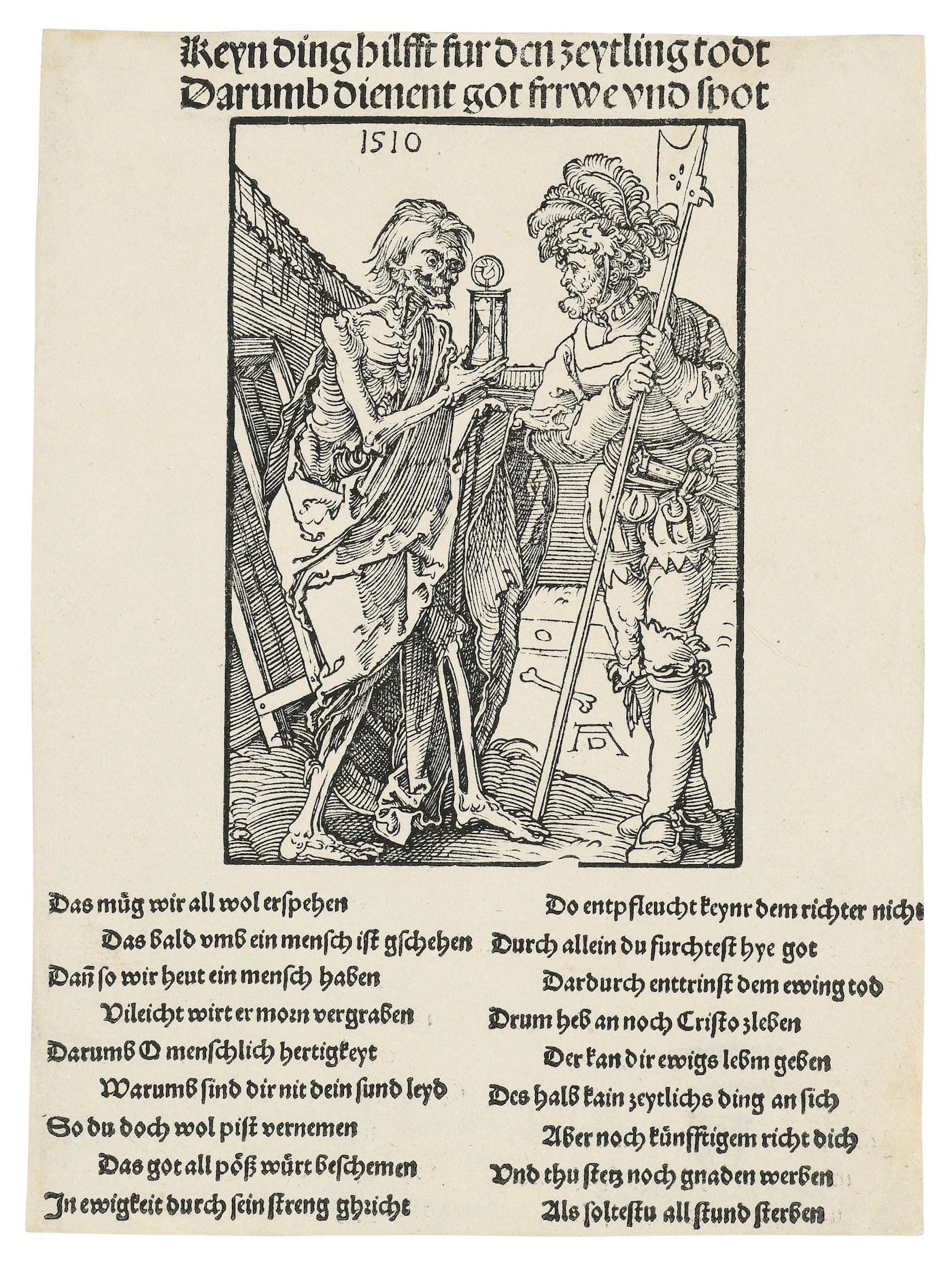

Ridinger’s print is one of the highlights in Christie’s ongoing online auction “Death and Desire: Prints from the Collection of Giancarlo Beltrame.” The 54 lots, which include striking examples of memento mori and vanitas images, span from the 15th to the 20th century and demonstrate an array of European attitudes towards death. The sale offers a number of works by Albrecht Dürer (including his famous “The Four Horsemen”), as well as many rare prints, such as two by Edvard Munch: a drypoint of nude women observing a skeleton and an erotic lithograph of the mythological Harpy ready to prey on a man’s skeleton.

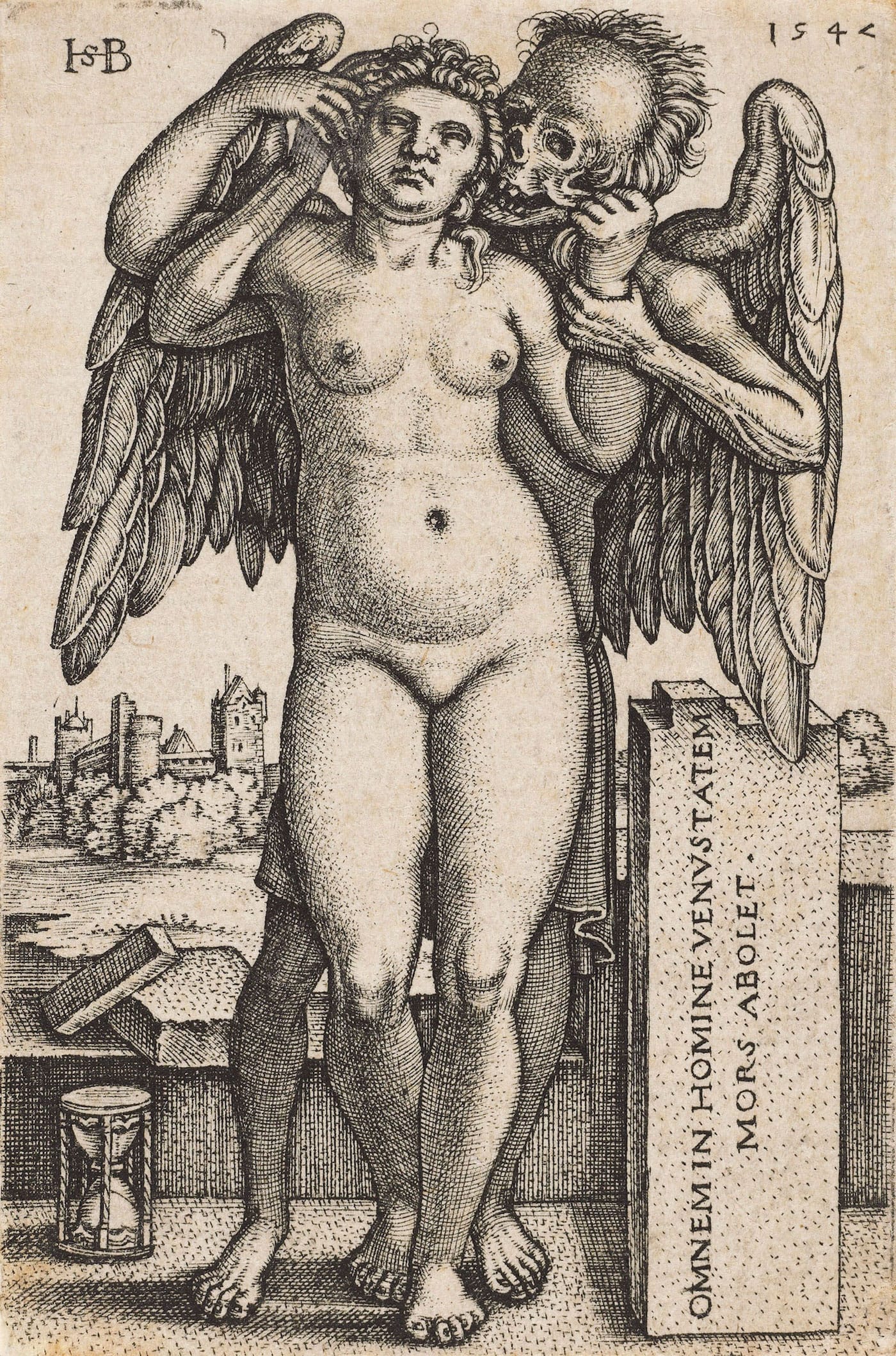

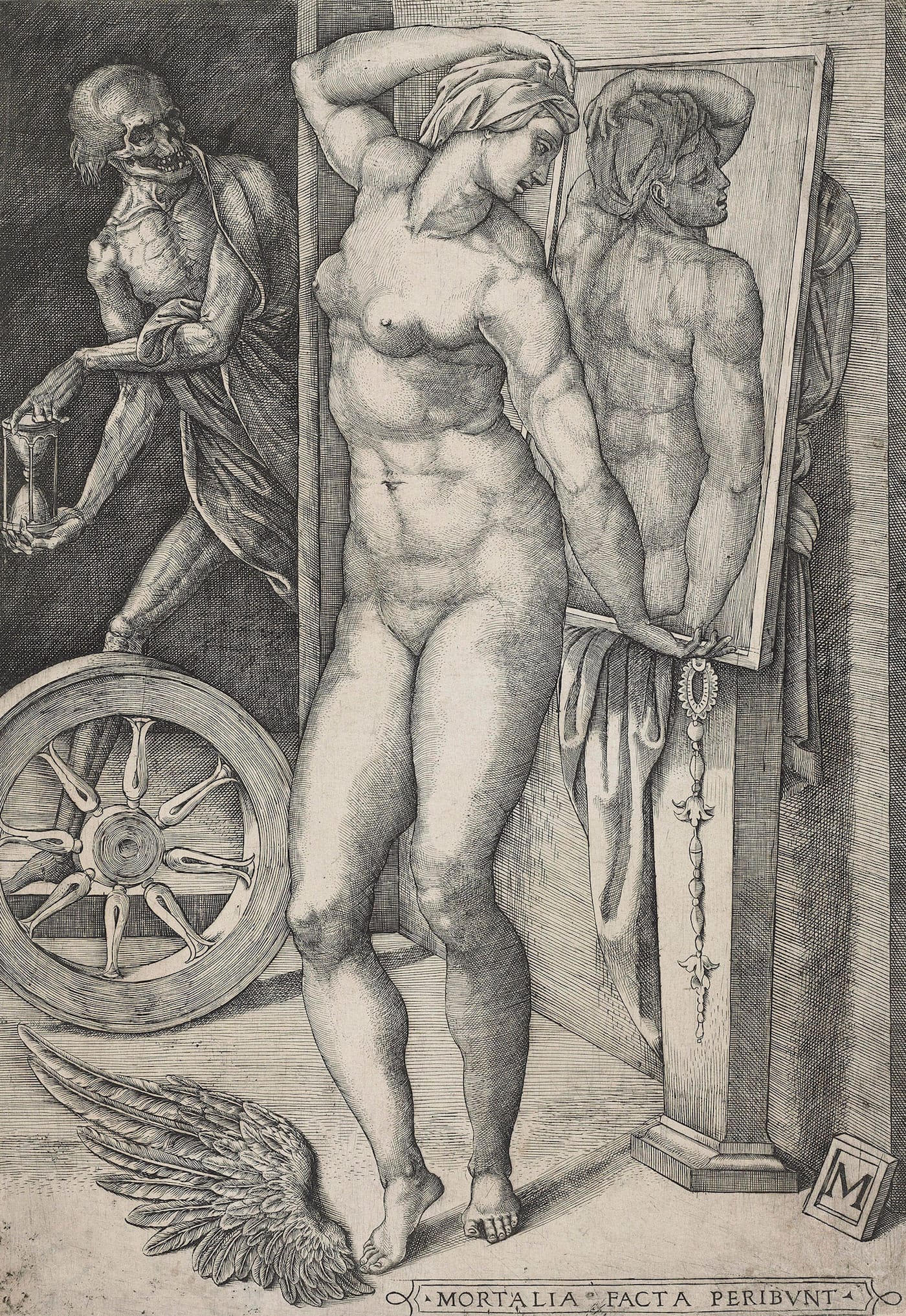

Death appears as the ultimate, triumphant figure in quite a few of the collection prints, although Ridinger’s is perhaps the most overt about the message. In one incredibly creepy engraving by German artist Hans Sebald Beham, death is shown as a winged man with a fleshless face, and he firmly grips the wrists of a naked woman as he holds her close. The print is just three inches long, but Beham took care to include a message on a plinth. As translated from Latin by Christie’s specialist Tim Schmelcher, it reads, “All human beauty is abolished by Death.” Driving home the point is an hourglass that stands at the pair’s feet, with most of its sand collected in the lower half.

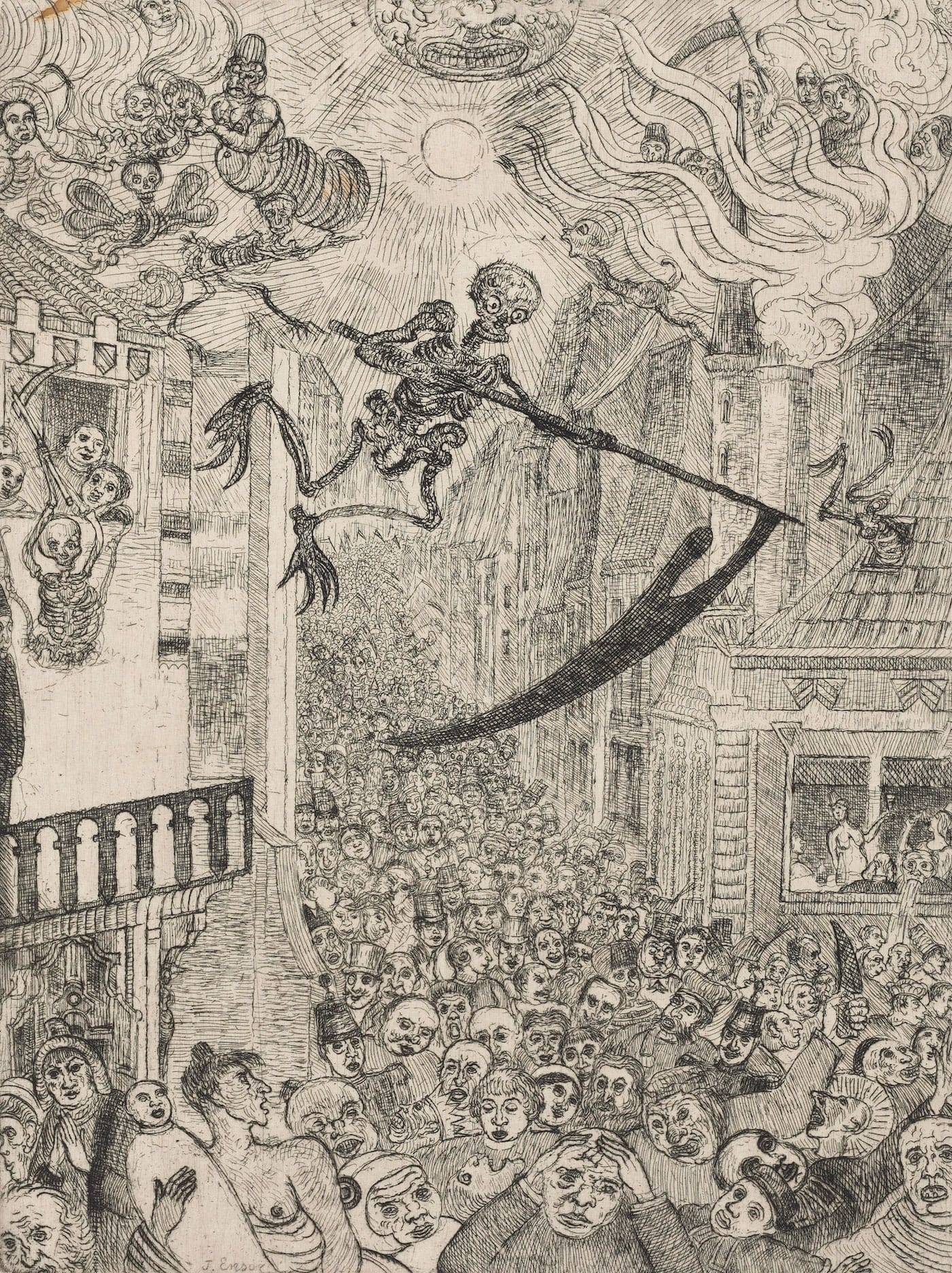

James Ensor, known for his expressionist and sometimes surreal paintings, offers a more comical — but still dark — vision of the fate that awaits us all. His 1986 etching shows Death as a black, scythe-wielding, wide-eyed figure flying over a crowd of terrified humans who fill the street. As Schmelcher points out, the doomed include all kinds of people: peasants, soldiers, monks, judges, and even kings.

The most bizarre procession in Beltrame’s collection, however, is found in an early-16th-century work by the renowned Renaissance engraver Agostino Veneziano. “The Carcasse (‘Lo Stregozzo’)” depicts a witch riding a skeletal monster through the underworld, accompanied by men, children, animals, and monstrous creatures. It’s mesmerizing not only because of its mystifying details but also its dynamism, with bones, limbs, plants, hair, fur, and the wind all integrated to form a swirling, charged scene. Veneziano’s engraving suggests a chaotic world that awaits once the inevitable time has come for death to seize us all.

The auction “Death and Desire: Prints from the Collection of Giancarlo Beltrame” continues online at Christie’s through November 3.