Berlin Artist Walks the Streets With 99 Smartphones, Prompting Google Maps Traffic Jams

Simon Weckert's conceptual Google Maps Hacks leads us to question the power of maps as a daily tool and control mechanism.

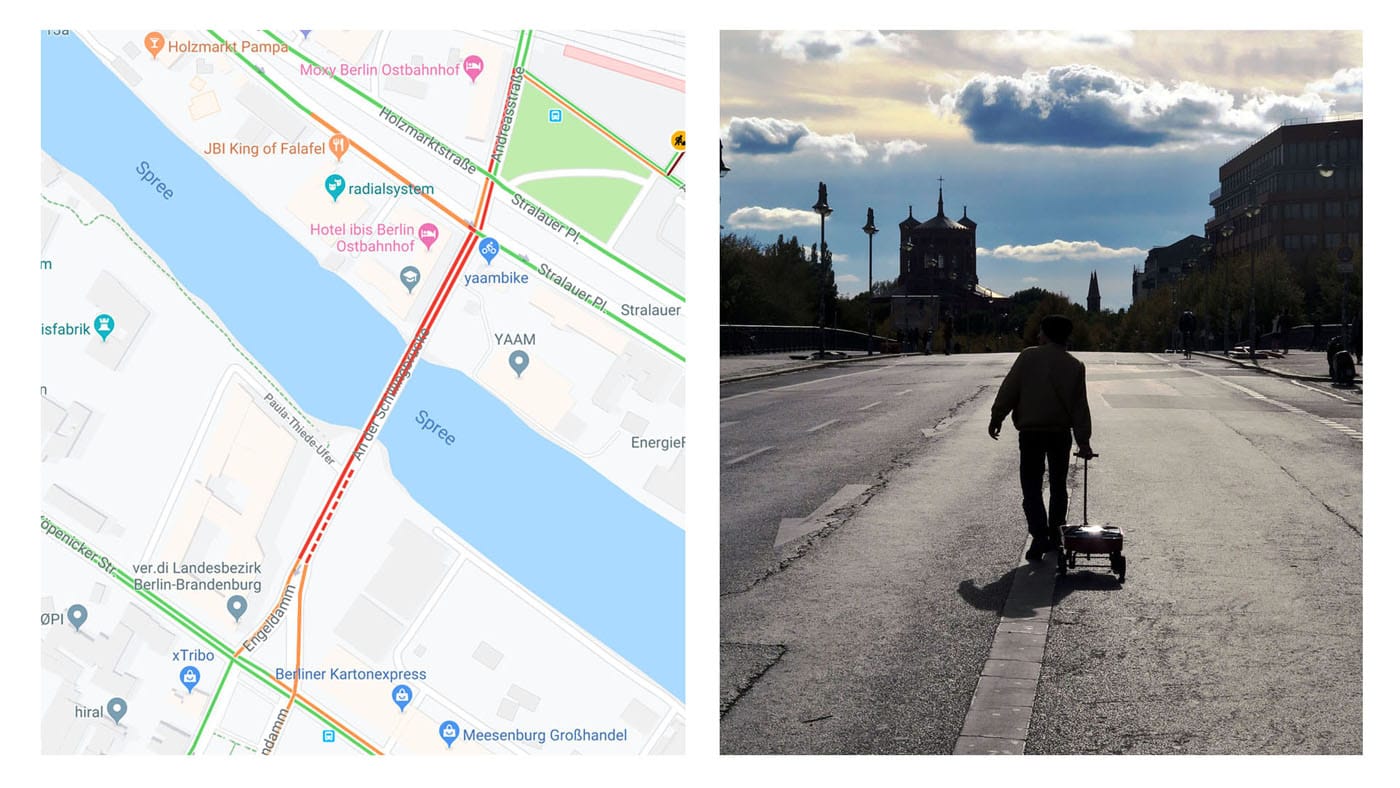

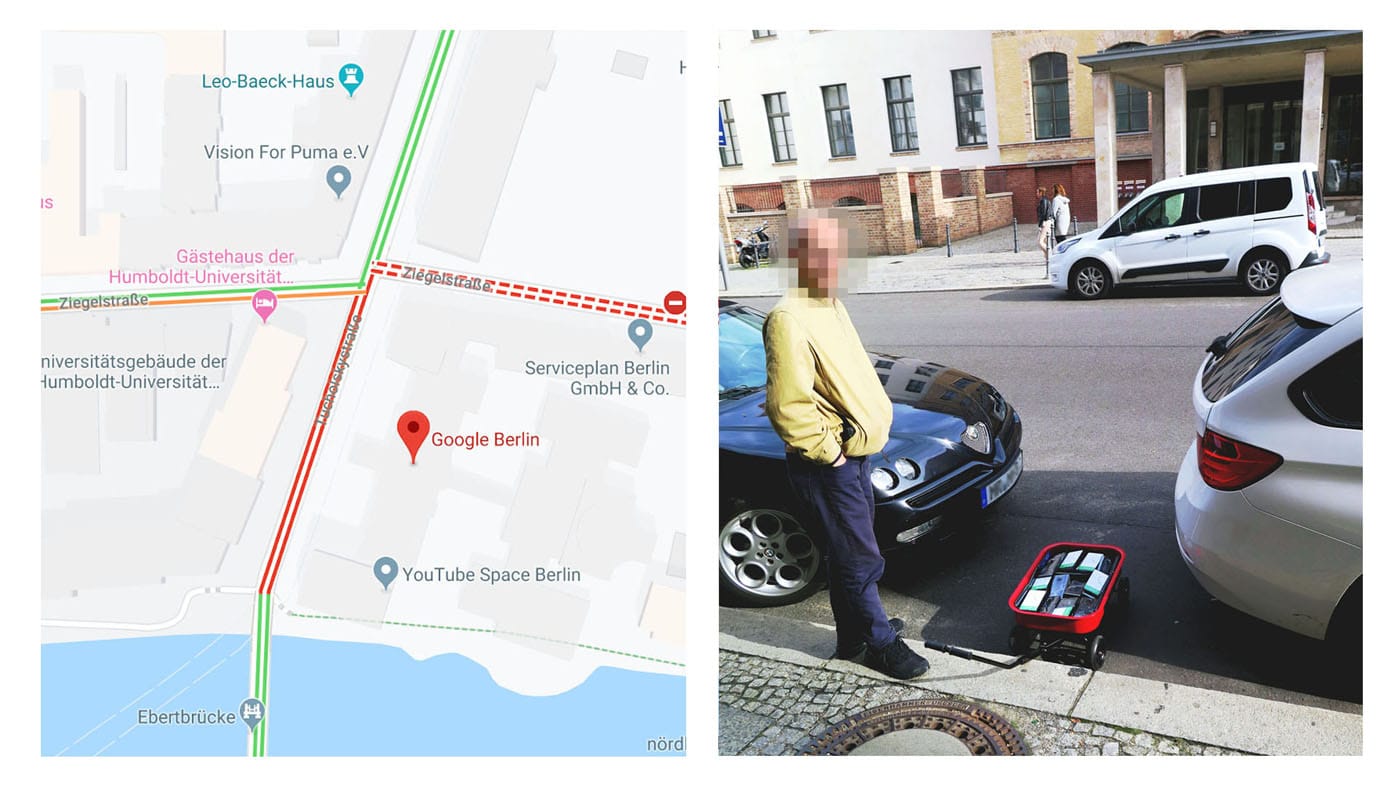

This decade has witnessed the ever-increasing overlay of technology on physical reality, especially as smartphones have become omnipresent tools of everyday life. The average first-world person’s reliance on mobile technologies, particularly navigational tools like Google Maps that chart routes through the world based on a real-time aggregation of digital information is often framed as a convenience — but for Berlin-based artist Simon Weckert, it also presents an opportunity to play around with the power structures inherent in these systems. This month, the artist managed to create a virtual traffic jam across one of the main bridges spanning the Spree river in Berlin, by walking the streets towing a hand wagon laden with 99 active cell phones.

“Google’s map service has fundamentally changed our understanding of what a map is, how we interact with maps, their technological limitations, and how they look aesthetically,” explains a statement by Moritz Alhert accompanying the project, Google Map Hacks. “In this fashion, Google Maps makes virtual changes to the real city.”

In a short video documenting the project, Weckert can be seen walking along with a Radio Flyer-type red wagon full of cell phones, juxtaposed with Google Map footage that turns his course red, as the platform reads the presence of 99 slow-moving mobile signatures as a traffic jam. Weckert’s statement highlights the impact of tech tools of all kinds — including Air BnB, ridesharing apps, Tinder, and food delivery services — on the development and character of cities like Berlin, and the manner in which we lead our lives and pursue our respective Maslow hierarchies. But the artist is also examining the historical and contemporary power of maps as a tool and control mechanism, and the gaps in the system that allow the average person to take some of that power back.

“With its Geo Tools, Google has created a platform that allows users and businesses to interact with maps in a novel way. This means that questions relating to power in the discourse of cartography have to be reformulated,” said Alhert’s statement, “The Power of Virtual Maps.” “But what is the relationship between the art of enabling and techniques of supervision, control and regulation in Google’s maps? Do these maps function as dispositive nets that determine the behaviour, opinions and images of living beings, exercising power and controlling knowledge?”

Certainly, we are all prone to use tech tools when they serve us, often without thinking about the ways in which they may deprive us of another kind of agency, or even undermine our ability to process and determine reality. If Google Maps thinks there’s a traffic jam, it will dutifully route people away from a street, or indication of its presence may deter someone from embarking on an intended journey altogether. It is the way of capitalism to always highlight the benefits of lifestyle amenities, and never offer or even consider mention of the cost. Weckert’s project is, on its surface, playful and clever, but it scratches the surface of the deeply insidious underbelly of allowing our tools to determine our courses in the world.