Half a Century of Black Art in Detroit

An exhibition revisits the ongoing legacy of Gallery 7, a space dedicated to Black artists experimenting with abstraction and minimalism in the 1970s.

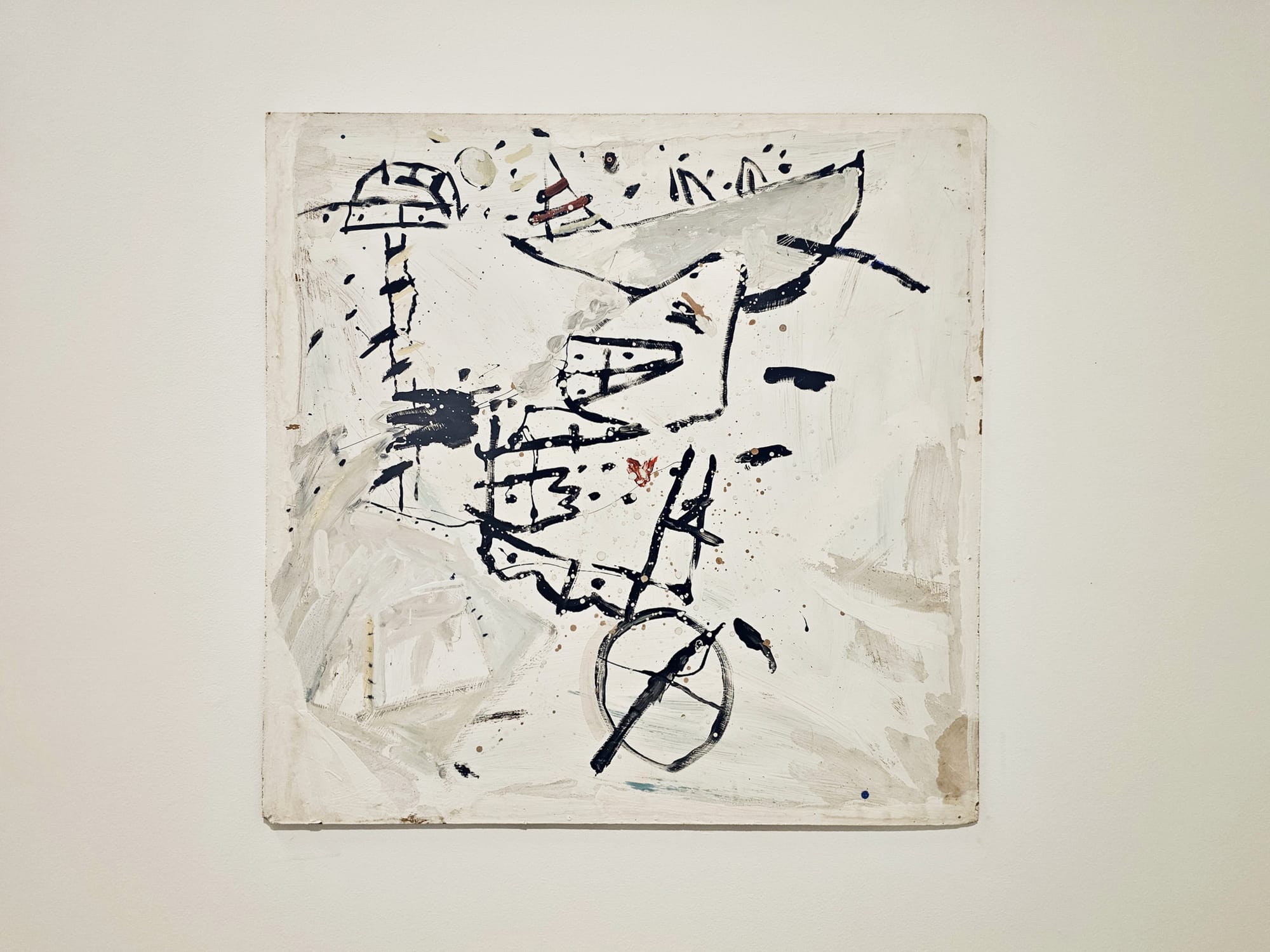

DETROIT — In 1969, muralist and sculptor Charles McGee parlayed his rising fame into the Detroit-centric exhibition space Gallery 7, which was dedicated to Black artists experimenting with abstraction and minimalism. The gallery operated for the next decade — one of the most turbulent in the city’s history. That period spanned fallout from the 1967 uprising, during which the National Guard and other entities of the police state suppressed Black activists' demands for civil liberties, leading to intensified White flight to the suburbs and divestment from city services and systems. Amid that social tumult, art and identity flourished in Detroit’s majority-Black environs, where the social realism favored by many within the Black Arts Movement found a counterpoint in the work of artists exploring African influence and abstraction, including geometric motifs, jazz-inspired compositions, and West African masks and textiles. Kinship: The Legacy of Gallery 7, curated by Abel González Fernández and currently on view at the Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit (MOCAD) through September 8, showcases key works by artists in the Gallery 7 fold, demonstrating that commitment to Black art in the city can't just be a thing of the past.

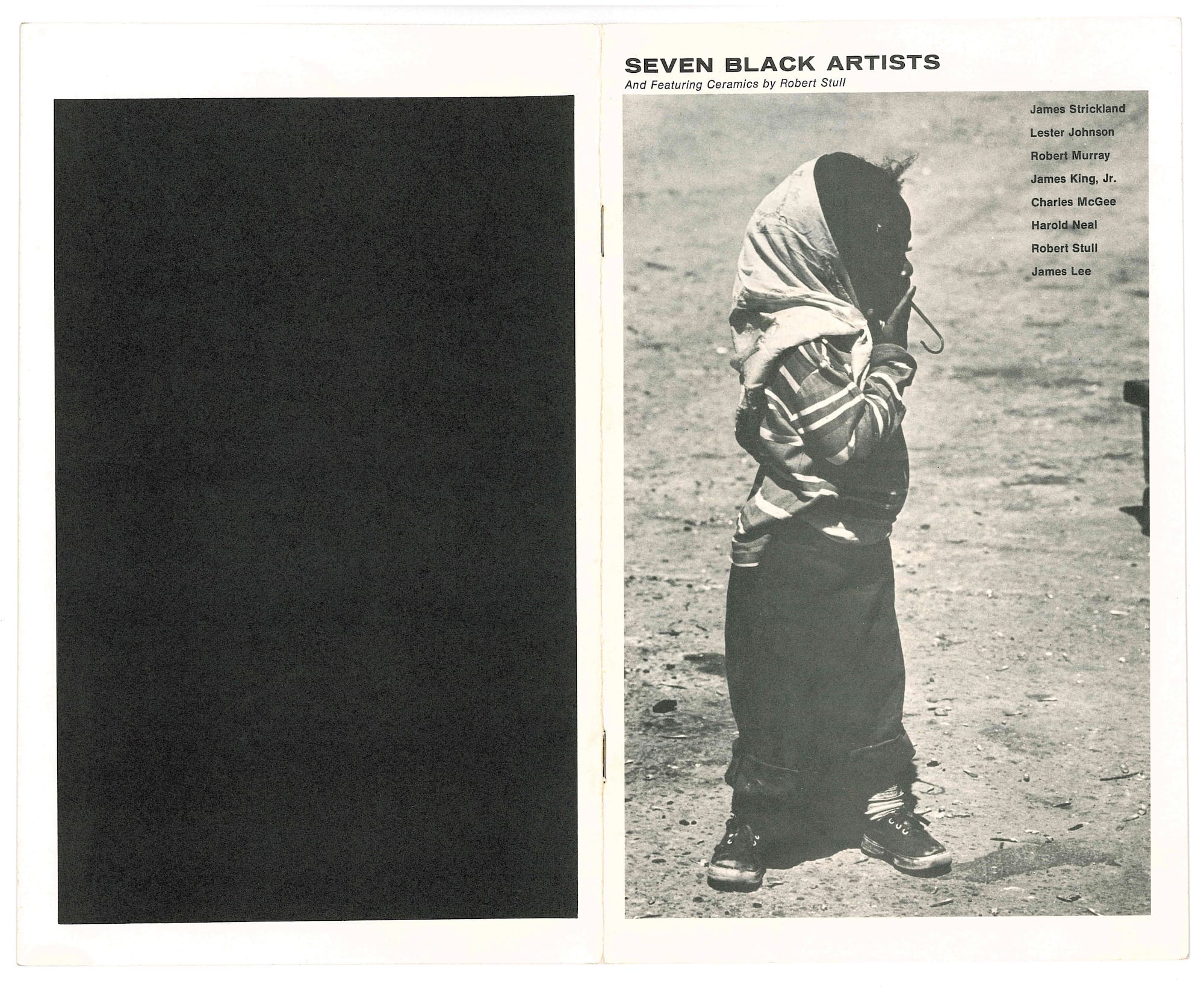

McGee, who passed away in 2021 at the age of 96, was inspired to open Gallery 7 after curating a well-received group show of seven Black male artists at Detroit Artists Market in 1969. Four of the artists in that show — McGee, Lester Johnson, Harold Neal, and Robert J. Stull — are included in Kinship, as well as abstract painter Allie McGhee. Fernández also includes a later generation of artists in this show, including Naomi Dickerson, Gilda Snowden, and Elizabeth Youngblood. Though not all of these artists interacted directly with Gallery 7 during its active years, they have an affinity with its mission and artistic values, and Dickerson, Snowden, and Youngblood add much-needed gender parity to the 1969 show.

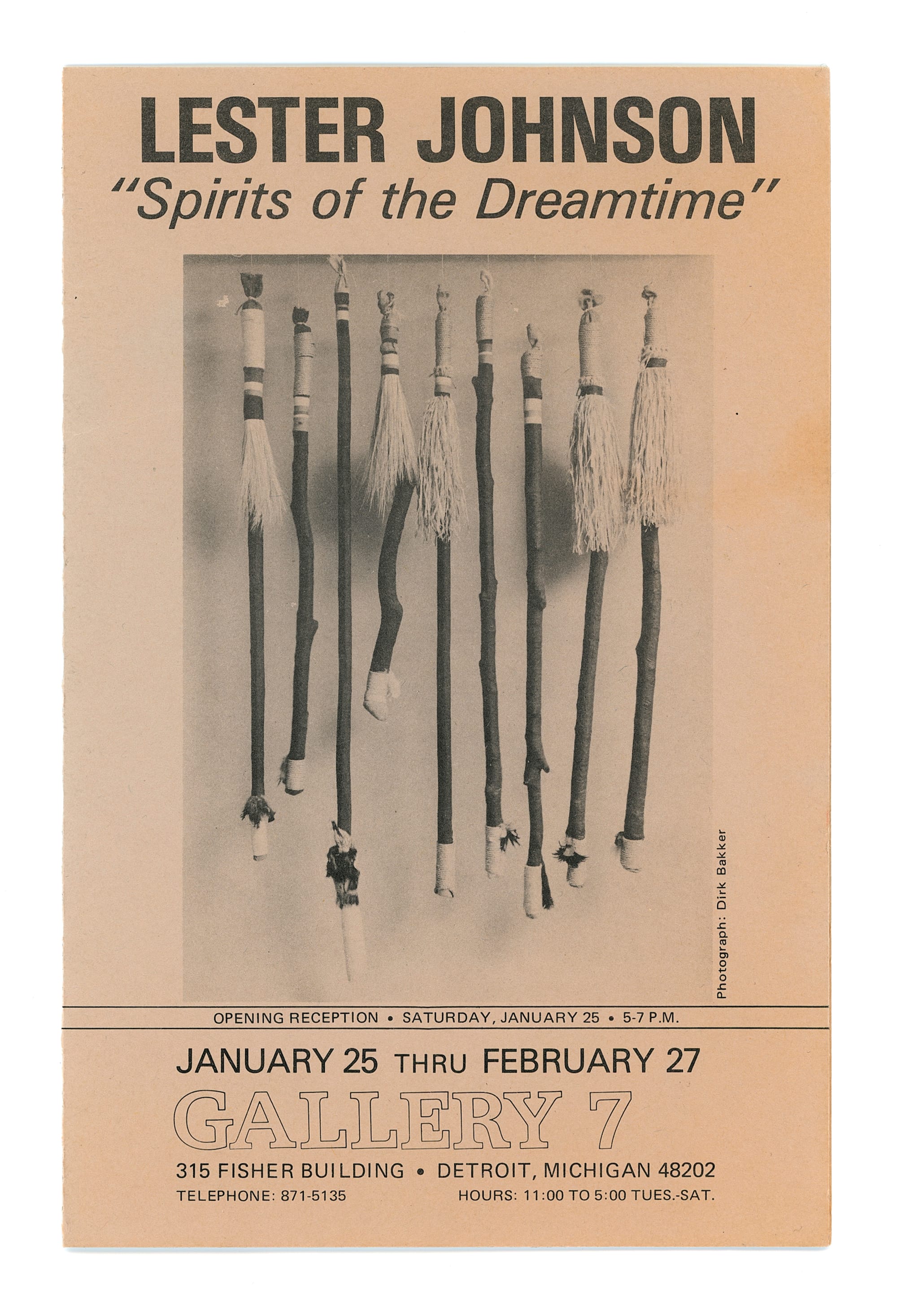

One of the most arresting visuals in the foyer to the exhibition is a wall-mounted series of ornamental staffs by Johnson, titled "The Sorceress and the Dreamtime Spirits" (1974), which was included in his 1975 solo show at Gallery 7, Spirits of the Dreamtime. In this early work, we can see the roots of Johnson’s longstanding experimentation with creating sculpture inspired by Yoruba cultural practices of adorning objects with fibers, shells, and beads to confer ceremonial power upon them.

“When I started doing research for the show, exhibiting artist Lester Johnson opened his archive for me,” Fernández told Hyperallergic. “Not only did I find a masterwork that was left in storage for more than 30 years, but I also got to explore the great history of a generation working in the context of the Black Arts Movement, Minimalist and abstract art, the Civil Rights struggle, and Pan-Africanism.”

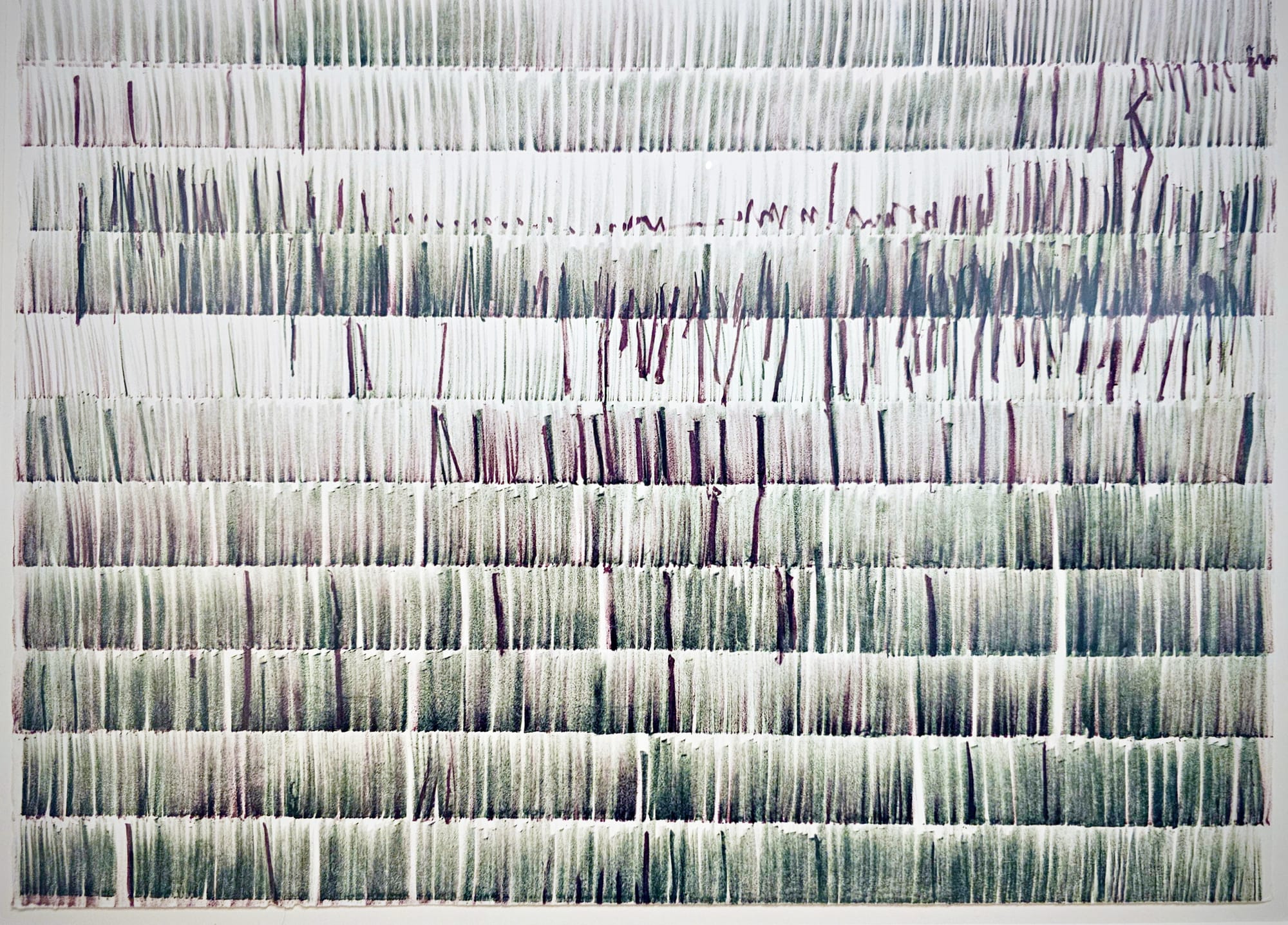

Abstraction still appeals to the younger artists in the show, as seen in Youngblood's sculptural forms and graphite drawings. The artist was drawn into the Gallery 7 circuit during her undergraduate studies at University of Michigan, and was encouraged by McArthur Binion — who had one of his first solo shows at Gallery 7 in the 1970s — to pursue graduate studies in design at the Cranbrook Academy of Art, just outside of Detroit. Kinship features one of Youngblood’s newer works, “Untitled” (2024), a bold, swooping painting on mylar, as well as two 2015 sculptures, “Lean” and “Loop 8,” both of which evoke starkly gorgeous jewelry with the spare materials of black wire suspending porcelain elements. And a 1976 lithograph by Dickerson, “Second Score for Black Opera,” accrues minimalist tick-marks into a composition for an imagined soundscape.

“Detroit is a city where the artist as curator, and artist-run spaces, thrive," Jova Lynne, MOCAD’s artistic director, told Hyperallergic. "Kinship is just one of many upcoming shows where we will honor the spirit of the artist-led community."

It is truly heartening to see MOCAD, which has struggled in the past to find its identity as a steward of the arts in Detroit, lean into the real strength of the city: its local artists.