Hinting at Indescribable Desire through Lush Paint

Do you know Adonis? He's not like those other male nudes that only exist to flaunt their bodies. Adonis has a touch of the ethereal. Delicate, almost elvish, features lend a gentleness to his face. He's taut but not Herculean. He is mature but retains the slim, willowy frame of youth. This special k

Do you know Adonis? He’s not like those other male nudes that only exist to flaunt their bodies. Adonis has a touch of the ethereal. Delicate, almost elvish, features lend a gentleness to his face. He’s taut but not Herculean. He is mature but retains the slim, willowy frame of youth. This special kind of male nude, named after the one and only boy that enticed Aphrodite, who could have had any man she wanted, takes center stage in Chilean artist José Pedro Godoy‘s show of recent paintings.

One of the strongest works in the show is “The Boys” (2013). Two young men wade in glistening blue water. One sports cherubic curls as the pool’s rays of light shimmer on his chest. He casts his gaze far away into the deep, perhaps absorbed in a daydream. The other boy is almost entirely submerged. His crew cut, nose, and eyes lurk just above the surface. He stares intensely at the other, dazed Adonis. In that gaze, there is a heat only understood by cats, dogs and teenagers. Is that staring figure daydreaming about what comes next?

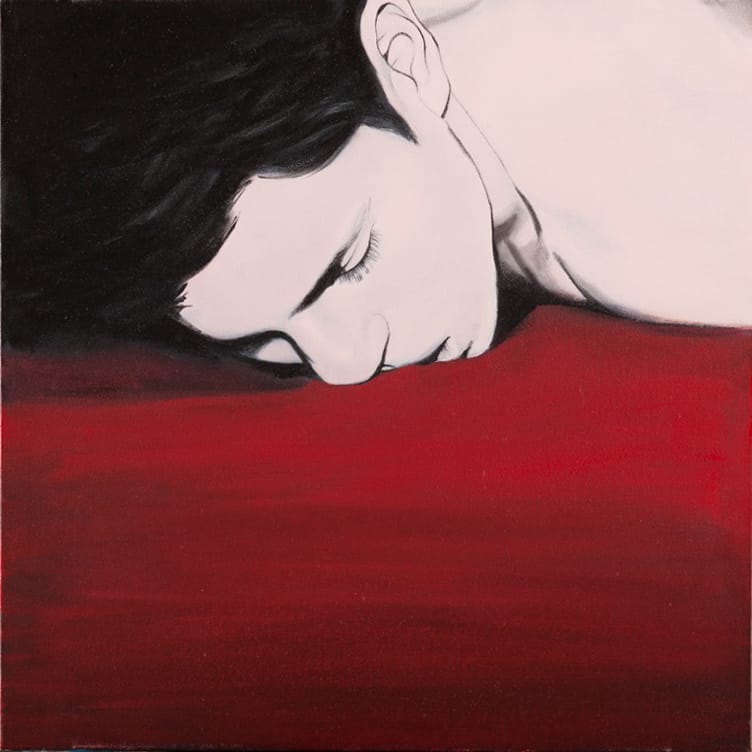

In “The Boys,” the colors shine with a lush oily finish, which reinforces the sensual (and perhaps soon to be oily?) content. The intensity of the colors and shade is the product of Godoy’s unique painting technique. First, he starts with a drawing layer. The second layer is a thick black and white painting of the composition — like hyperrealism in grayscale. This step enables him to carefully shade out the composition and balance light and shadow. He then covers it all with a final layer of color in a process that could be likened to to coloring inside the lines of the book page he created for himself. The result is bright luminosity and rich dark shade that dramatizes and mystifies his subjects.

In the one work in the show in which Adonis doesn’t appear, Godoy left a large painting of a jungle, “Paradise Found” (2013), in its grayscale stage. It still looks tropical, verdant, and intense despite its lack of color. It’s a lesson that vibrancy is not just about color but also about entrancing dynamics of light, shape, line, and shade, successful in its formalist tendencies.

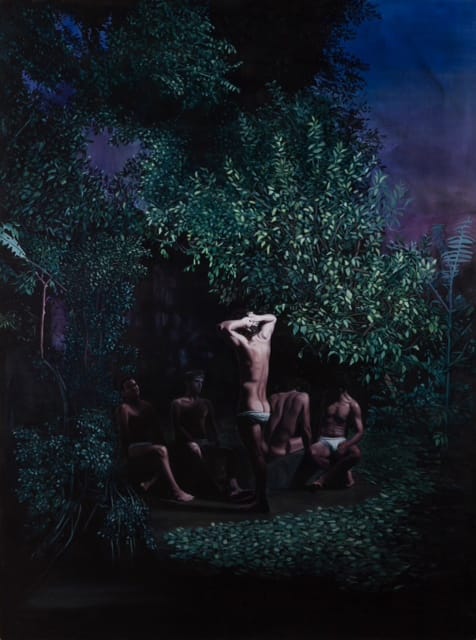

There is a cluster of paintings in the show featuring young men in forest settings. In “The Nature of the Bestiary II” (2013), five men languish in the woods. They look blasé and non-chalant as though something left them stunned and lethargic. In the most explicit work, “The Nature of the Bestiary I” (2013), seven nudes are placed in the forest. One caresses his chest in the far left of the picture. Another crouches on his knees near the self-masseuse. In the center, a youth sprawls out in a twisted pose. An Adonis above him unleashes a golden shower. Three nudes to the right seem unaware of this kinky gesture. Caught up in a trance, their attention is diverted elsewhere. The shadows cloaking the entire scene reinforces the mystery in the statuesque figures’ faces.

In the writing of this review, it has been hard not to overuse the word dreamy. Entranced faces stare out into an existential abysses. Forests look enchanted, ripped from fairy tales or A Midsummer Night’s Dream. This atmosphere is fitting for Adonis because desire is so enigmatic and mysterious. Don’t we enter into a trance when we go for it? Haven’t we all felt spellbound and done things that felt right in the heat of the moment, but look other-worldly and strange in retrospect?

To indulge in the perfunctory Michel Foucault quote, “People know what they do; frequently they know why they do what they do; but what they don’t know is what what they do does.” In other words, we sort of get it and we sort of don’t get it. Godoy packs that internal paradox into his paintings.

It’s tempting to label these works as homoerotic. While the paintings aren’t afraid to show charged scenes, they are also cold and rife with ambiguity. To be fair, in some works, they could just be dudes that feel so safe with their sexuality they can be nude with each other. But really? The handsome boy with delicate features has been an established cypher for centuries.

The mystique in Godoy’s work is refreshing — far too much gay art is painfully obvious. All those twee images of gay couples holding hands have the iconographic depth of a meme-ready kitten pic. Explicit erotica can never look so original when the internet is full of it. Godoy’s work, in contrast, is admirable for its willingness to leave something to the imagination and revel in the stuff of daydreams. When so much of desire is actually about indescribability, the artist’s less obvious route actually captures more of the magic.

The Beloved is on view at White Box (329 Broome Street, Lower East Side, Manhattan) through April 11