ArtPrize and Its Discontents

CHICAGO — At surface value, ArtPrize is all giant flowers, mythical dragons, yarn-bombed trees, and cash galore. Begun in 2009, the annual event attracts thousands of visitors from Michigan and elsewhere, a strange combination of populism and art world elitism wrapped into one — but it is not an ide

CHICAGO — At surface value, ArtPrize is all giant flowers, mythical dragons, yarn-bombed trees, and cash galore. Begun in 2009, the annual event attracts thousands of visitors from Michigan and elsewhere, a strange combination of populism and art world elitism wrapped into one — but it is not an idealistic “coming together” of the two populations.

The public-vote awards $200,000 to the winner plus another $160,000 for the top 10. Affectionately and hatefully referred to as DragonPrize for the many representations of this mythic beast, ArtPrize engenders Tumbler blogs such as ArtPrizeWorst, among many online forums that offer pointed critique and just plain anger. With the addition of the juried prizes last year — which include a $100,000 prize and five more $20,000 juried awards in specific categories — there is still hope that good art can be found in ArtPrize, an experiment in distributing large sums of money from the ultra-rich and ultra-conservative DeVos family, who are regular donors to the Republican Party, brush shoulders with the Koch Brothers, and are notoriously against gay marriage.

Artists must pay a $50 entry fee to show work in ArtPrize. They must also ship their work to ArtPrize and, if they care about their work, they are encouraged to purchase their own insurance. The event is almost entirely volunteer-run, and venues must agree to stay open during ArtPrize hours during the extensive three-week run of this event. With the exception of Paul Amenta’s smartly curated SiTE:Lab and the public intervention of yarn bombing, the cacophony of visual stuff plastering the walls of Grand Rapids establishments made it nearly impossible to think straight about any one or two particular visual works.

There are quite a few reasons — monetary, political and creative — not to participate in the spectacle-inducing, sensationalized event that is ArtPrize. I spoke with three members of the Grand Rapids art community — Chris Cox, co-owner of Gaspard Gallery, Anna Campbell, Assistant Professor of Art at Grand Valley State, and George Wietor, cofounder of The Division Avenue Arts Collective — about why they did not involve themselves with ArtPrize this year.

Chris Cox, Co-organizer of Gaspard Gallery

Walking down Division Street past the array of yarn bombings and the Take Hold Church, I started to notice the city changing. More people were waiting for buses, there was a faint smell of booze lingering, and the glossy ArtPrize venues signs were gone. On my walk I happened upon Gaspard Gallery, a space I checked out last year during my visit to ArtPrize. The gallery hosted their inaugural exhibition, Spiritual Lake, during the event, and showed a gorgeous underwater landscape of bodies floating and colliding with one another. Last year, the series by Grand Rapids-based photographer Chris Cox was a welcome break from the many ArtPrize sculptures of big things made of many little things like this year’s “Tired Panda,” a top 10 finalist. This year I returned to Gaspard — a gallery that takes its name from the Persian word for “treasurer” — in hopes of seeing more of the same.

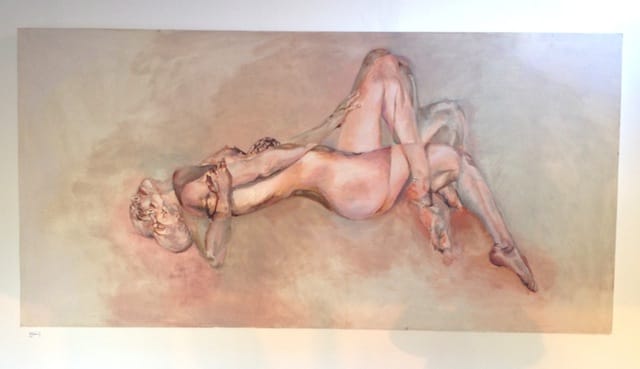

Gaspard did not participate in ArtPrize this year, but they did allow me to peek in at their current fall group exhibition which is an assortment of ghostly photos by Cox, Sammie Madson’s “Form in Motion 1,” one slice of a triptych that appears like a David Lynchian painted body that appears like a hallucinatory vision of twins, and a scratchy minimalist painting of pink with white chipped away from its core.

“It’s tough — people have been asking me why I didn’t participate in ArtPrize this year,” Cox told me when we chatted via phone. “From my perspective, there is only so much you can get from ArtPrize. For the artist who thinks ‘I am going to go to ArtPrize, win the public vote, and have a career’ — I don’t think that’s realistic. Of course $200K would help you a lot, but I’m not sure it would give the critical acclaim people expect from that.”

Cox noted the opportunities for exposure that came from showing at ArtPrize, including getting work seen by Jerry Saltz and yours truly. He tells me that he doesn’t have anything against ArtPrize in general — but this year the timing just didn’t work out.

“It’s really cool that a small town like Grand Rapids can get people to come look at art work,” says Cox. “A lot of it is shit, hung terribly, but I think that’s a representation of art in general. I try to go out to every exhibition, and have really only seen a few great local shows in the past few years.”

Anna Campbell, Associate Art Professor at Grand Valley State

Professor Anna Campbell and I met for dinner at Pub 43, a cozy tavern known for being both gay and artist-friendly. On a TV screen in one corner, a video art piece of a lens going in and out of focus while traveling over domestic items played on a loop. Campbell showed her work here in the 2009 inaugural ArtPrize. She created custom-made coasters that critiqued the source of ArtPrize’s funding, calling out the DeVos family’s anti-gay marriage agenda. She only printed 1,000 coasters; within a few days, they were gone. Had she known, she says she would have printed thousands more. For the three years after her initial ArtPrize debut, Campbell hopped on as an assistant juror. Having just returned from a sabbatical this year, Campbell decided not to participate at all. Of her initial coaster project, she notes that “I felt like there is no way for me to participate in this thing that isn’t institutional criticism — I cant ignore the frame to do something else.”

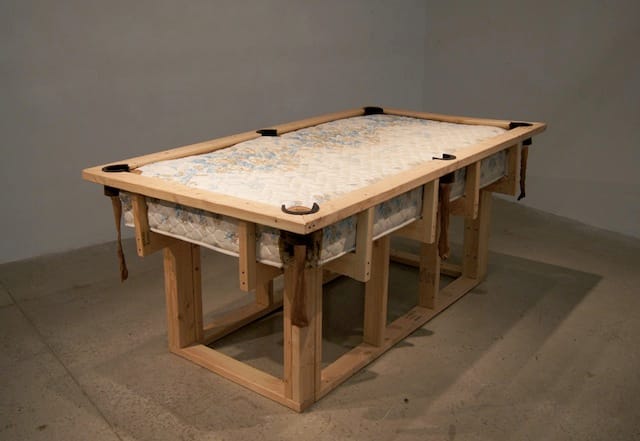

That said, sharp political art like this is a departure from Campbell’s sculpture-focused practice, in which she retools commonplace objects, juxtaposing materials to create new forms. “A Pocket, a cue, a shot” (2013) is a mattress that doesn’t appear new tucked into a custom-made frame of a pool table. There are no balls to play with, but if there were they might fall into one of the pockets — a strip of pantyhose, dangling down, and the mattress is cut open in the corners, guts and dark insides exposed. The cue is nuanced, a subtle gesture from one viewer to another while standing across the table. In other words, this is not the type of work that one might find at the free-for-all ArtPrize.

“I would say that the frame of the question is not ‘why not choose to do ArtPrize — it’s not something that you sit down to decide, because there are not a lot of reasons to initiate participating,” says Campbell. “Because it’s so open, it doesn’t do anything for your CV. You get more traffic for work, but not traffic from people who can participate in a dialogue with you necessarily. I suppose if it were an excuse to show at the GRAM or Fred Meyers, that’s something I would think about and suck it up that it would be in an ArtPrize exhibit.”

The lack of curatorial options outside of SiTE:Lab and artist-run spaces, too, is another hindrance. “I’m teaching this curating class, and I am thinking about context and how that affects the work — or even just that I’m an artist and trying to make work that communicates and that you’ll be drowned out by art that is big objects made of smaller objects,” she explains.

That’s not to say there’s nothing redemptive about ArtPrize for people who do want to participate — not necessarily to further their art careers, but to get a chance at showing something to a lot of people. “There are two things that work in ArtPrize – it is a taste,” says Campbell. “So if you are seven, and you get to go downtown Grand Rapids at ArtPrize, and you won’t see art under any other circumstance, it is nice to have a taste. If you’re a 42-year-old guy and you like to make stuff in your garage and you see that someone made a giant lion out of 40,000 nails, and you think oh that’s art and its OK, that’s good, too.”

George Wietor, Cofounder of The Division Avenue Arts Collective

I reached out to Mr. Wietor, a dedicated member of the Grand Rapids art community who wears many hats, including actively producing and publishing artist-made books under the small independent publishing house and print shop Issue Press, and the cofounder of the nine-years-and-running Division Avenue Arts Collective, a volunteer-run all-ages music/art venue and DIY cultural space. Like Campbell, Wietor did not participate in this year’s ArtPrize, but did provide Hyperallergic’s Hrag Vartanian with commentary from last year’s event. He gave us permission to use his answers from 2012, and noted that he can’t speak to how things have changed or not changed this year. In response to a question about what ArtPrize could do to make the local art community feel more welcome, Mr. Wietor noted that people who were onboard after the first year seem to be pretty gung-ho still.

“You either love it, and acknowledge some of its faults, or dislike it and acknowledge some of its positive attributes,” says Wietor. “The artists who will always work for the promise of exposure will continue to participate, and I don’t really fault anyone for wanting to. But, I have little pity for those who do and are disillusioned with the process. You get what you pay for. Literally, you pay to participate.”

Is there an opportunity for ArtPrize to move beyond the guffaws and jabs of its DragonPrize moniker, among other problems, and be taken seriously by the international art community? After walking through the event feeling increasingly disappointed by the stuff on display, yet hopeful about some of the truly curious conversations happening in front of some works of art, I too wondered why there were not more lectures, panels, symposiums, or even artist-curator conversations?

“If ArtPrize wants to establish itself as a world class art event that is truly changing the way we interact with art, it needs to back it up with world class educational opportunities for the public at large and that can’t really happen in the amount of time it is allotted,” says Wietor. “Now that we are four years [at the time of this interview, in 2012] down the road, it seems like we can move beyond the gimmick of the purse size, and funnel some of that money towards things that actually improve our community’s understanding and respect for art – things that help people fully take advantage of their ability to vote.”

This would, of course, assume a sort of educational level that many of the folks who come out to ArtPrize do not have. And that is the fault of larger structural systems, of an America that does not value or support the arts and that regularly votes to cuts funding for the NEA and other arts organizations.

ArtPrize is not going to fix this larger systemic problem. But as Wietor says about the amount of money being poured into ArtPrize: “Could you imagine the kind of programming that $250,000 could support?”

ArtPrize in Grand Rapids, Michigan ran through October 6.