How the First Illustrated English Book Described the Universe

The first illustrated English book was ambitious, describing large ideas like the roundness of the Earth and why we experience day and night.

The first illustrated English book was ambitious, describing large ideas like the roundness of the Earth and why we experience day and night. The Myrrour of the Worlde, printed by William Caxton in 1481, was a translation of Gossuin de Metz’s 1245 L’Image du monde, itself based on the Imago mundi scribed by a 12th-century monk known as Honorius of Autun.

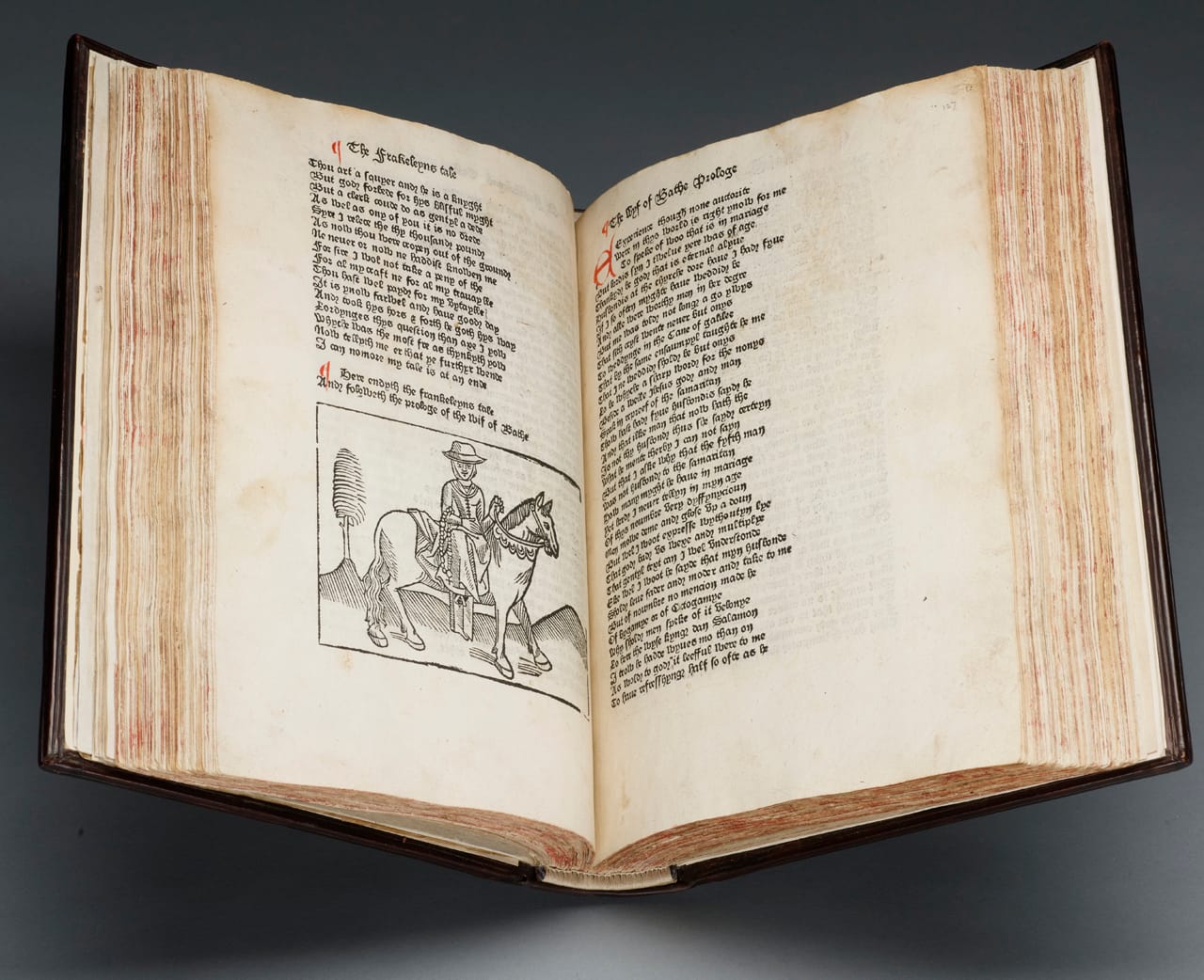

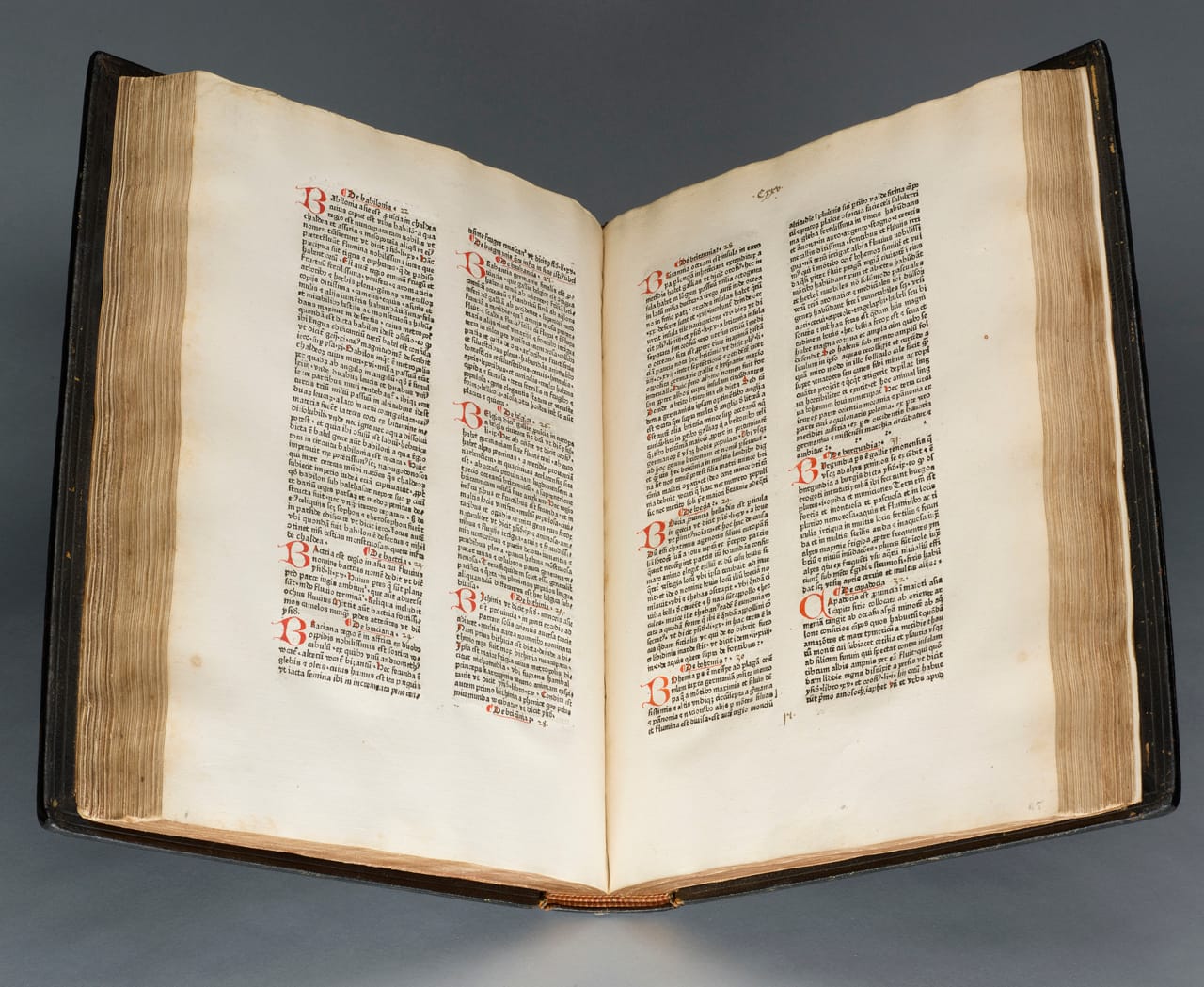

As one of the first to harness the new technology of printing and recognize the market potential in England, Caxton also published the first book printed in English. Another translation, this was in 1473–74 of Raoul Lefèvre’s Recuyell of the Histories of Troye, recounting the exploits of Jason and Hercules along with the legendary ruin of Troy. These books were essential to standardizing the English language, which in the 15th century was riddled with dialects. For example, when he printed the Canterbury Tales in the 1470s, Caxton chose Chaucer’s London dialect for the text. Currently at the Morgan Library and Museum in Manhattan, William Caxton and the Birth of English Printing explores this history and illuminates Caxton’s influence on the English language of today.

John T. McQuillen, assistant curator of printed books and bindings at the Morgan, explained to Hyperallergic that individual works by Caxton have appeared in other exhibitions at the museum, but the last show concentrating on his legacy was in 1977.

“That show was heavily based on the literary side of Caxton’s output and the works he translated himself,” McQuillen said. “At nearly 40 years, I thought it was high time to take another look at the history of early English printing by focusing on the physical aspects that show you how the books were actually used or intended to be used.”

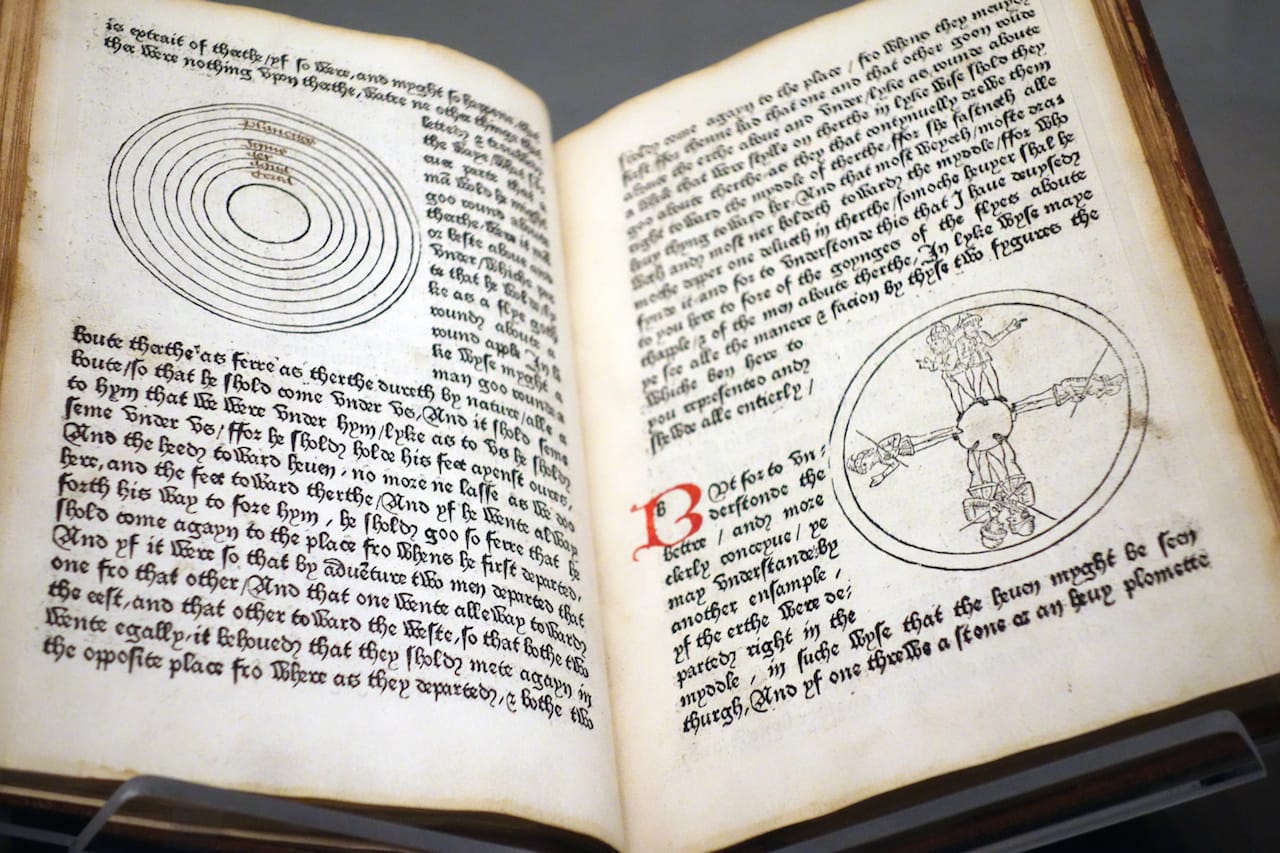

Pierpont Morgan, who valued Caxton even over Gutenberg, had the printer painted on the ceiling of his library’s East Room. Myrrour of the Worlde was part of a group of texts incorporated into Middle Ages education, much of the information gleaned from classical sources like Pliny and Strabo. McQuillen stated that the title “image” of the world “refers to the main part of the text focused on the description of the Earth and its attributes: its shape, size, relationship to the heavenly spheres, and other heavenly bodies (sun and moon).” Along with some historical information, there are descriptions of the Earth, the solar system, and eclipses.

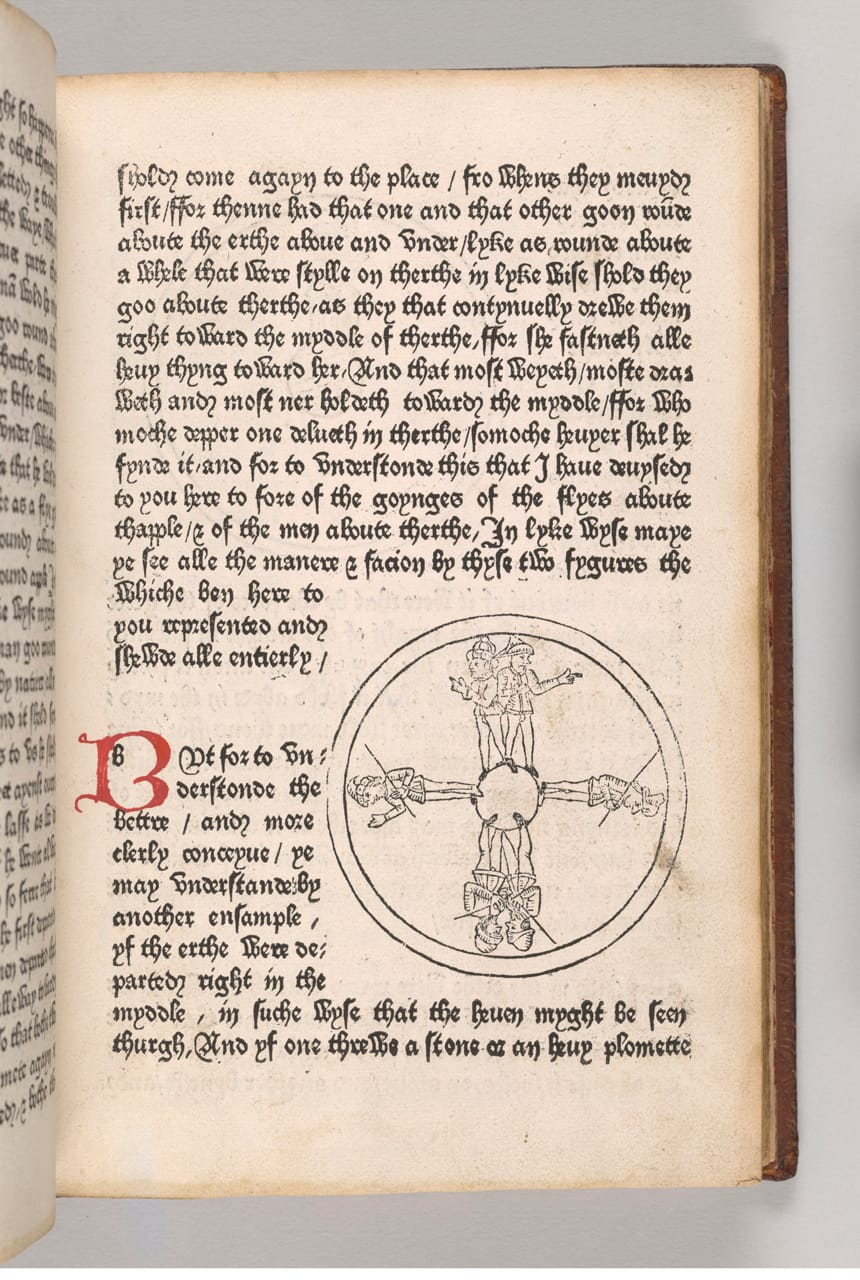

The round shape of the Earth is illustrated by two men who stand back-to-back, walking away from each other and meeting again on the circle. Another describes the same idea with a rock tossed through a hole sliced in the world, with it tumbling out the other side. “The really cool thing is, from Gossuin of Metz’s original French work through to Caxton’s English translation and publication of it, the images remain almost exactly the same,” McQuillen said, noting that he hasn’t discovered a good source yet for how, over two centuries, they remained so consistent.

This value on the images as part of the text is part of the reason Myrrour of the Worlde became the first illustrated English book. “It just goes to show how integrated illustration was in some texts and how important carrying that sort of visual description through different copies was,” McQuillen stated. “Print only carried on existing manuscript and textual traditions and did not radically alter them, at first. Anyone who wanted to buy this text would have expected it to have these specific illustrations, and Caxton provided that to them.”

William Caxton and the Birth of English Printing continues at the Morgan Library and Museum (225 Madison Avenue, Midtown East, Manhattan) through September 20.