How the Naming of Clouds Changed the Skies of Art

The clouds in many 19th-century European paintings look drastically different than those in the 18th century.

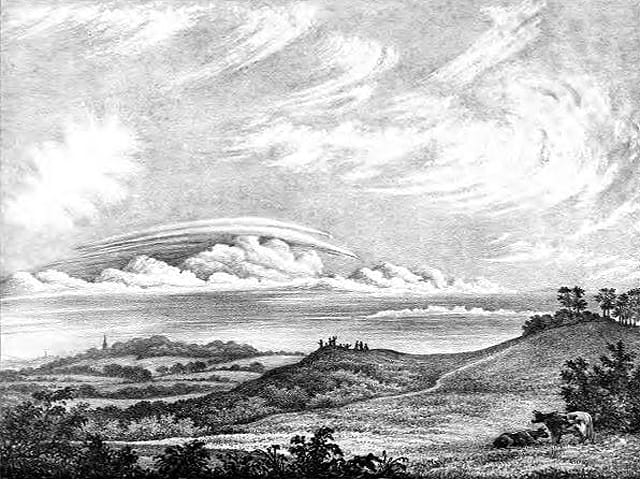

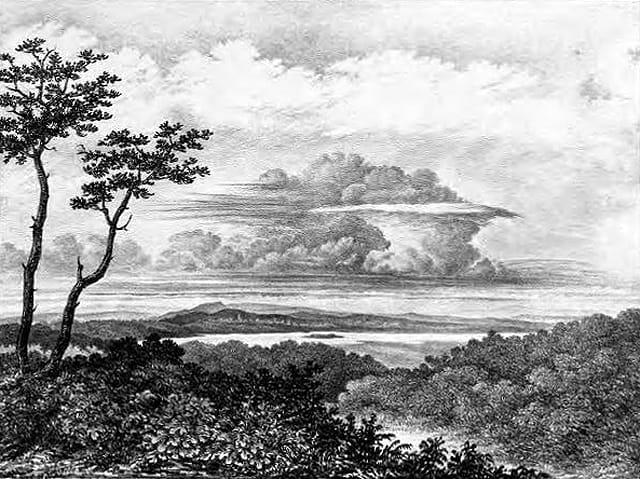

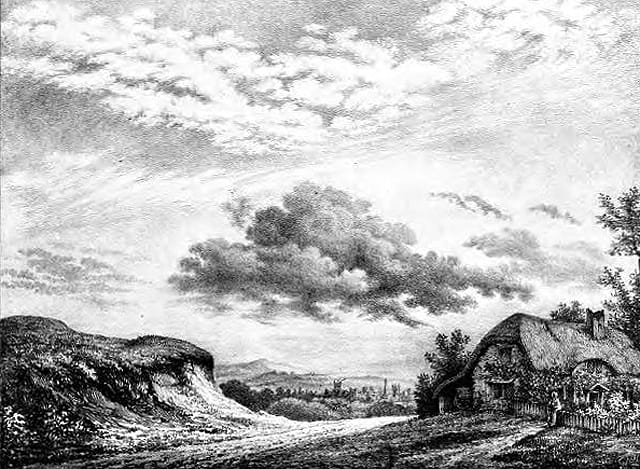

The clouds in many 19th-century European paintings look drastically different than those in the 18th century. There are layers to their texture, with whisps of cirrus clouds flying over billowing cumulus, and stratus hovering low. Clouds weren’t classified by type until 1802, and their subsequent study influenced artists from John Constable to J. M. W. Turner.

Luke Howard, a pharmacist by profession and an amateur cloud enthusiast, was born in London in 1772. By 1802, when he presented his Essay on the Modification of Clouds to the Askesian Society, he’d spent years monitoring the skies over his home city, and sketching their changing shapes to record their patterns. The entire essay is available at the Internet Archive, and Howard introduces the necessity of categorizing the clouds directly:

In order to enable the Meteorologist to apply the key of Analysis to the experience of others, as well as to record his own with brevity and precision, it may perhaps be allowable to introduce a Methodical nomenclature, applicable to the various forms of suspended water, or, in other words, to the Modifications of Cloud.

Others had attempted cloud classification prior to Howard, but their systems didn’t catch on. It seems hard to believe with most areas of natural study being thoroughly examined before 1802, and clouds always visible ahead, that no one had instituted a system for their forms. However clouds were mostly treated as individuals, wild and untamed by pattern.

Howard named them in three Latin terms: cirrus (“a curl of hair”); cumulus (“a heap”); and stratus (“layer”). Now 150 years after Howard’s death in 1864, the Science Museum in London exhibits some of his research tools and art in a small display. Some of his watercolors were created in collaboration with artist Edward Kennion, who likely refined the self-taught Howard’s sketches and paintings. Rachel Boon writes in a post for the Science Museum blog that it’s “been argued by historians of art and science that Howard’s contemporary John Constable was influenced by this new meteorological theory and it is visible in his powerful landscapes. Not only did Howard’s images inspire great art but so did his published essays which stimulated the imaginations of the poets Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Percy Shelly.”

In another post for the Science Museum, Victoria Carroll notes that not all artists were enthused by these boundaries. Caspar David Friedrich, who certainly appreciated an ominous cloudscape, “was concerned that ‘to force the free and airy clouds into a rigid order and classification’ would damage their expressive potential and even ‘undermine the whole foundation of landscape painting.'”

Friedrich mostly stuck to ethereal suggestions of clouds, not that different from the century before, but Constable, who did his own studies, and others like J.M.W. Turner, instilled their landscapes with dynamic texture and warring shapes that responded to this new science. Clouds were no longer just fluffy afterthoughts, they were temperamental and majestic, with all the the complexity of nature.

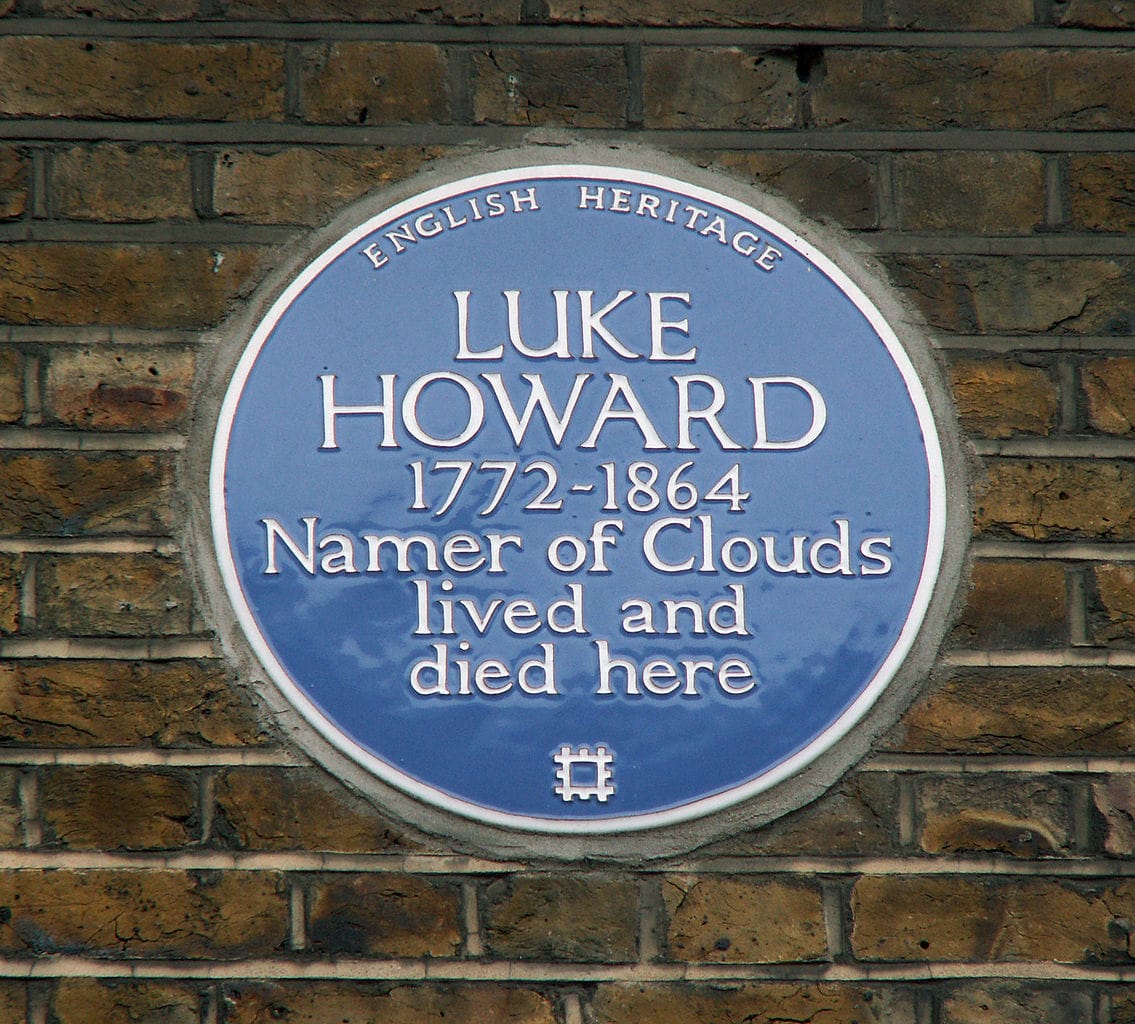

Howard’s former home at Number 7 Bruce Grove in Tottenham, London, where he died at the age of 91, has unfortunately fallen in to disrepair, with a grassroots effort underway to protect it through the Tottenham Clouds group and Tottenham Civic Society. Yet on its brick façade a prominent blue plaque still proudly announces: “Namer of Clouds, lived and died here.”

The Science Museum in London is on Exhibition Road, South Kensington, London.