In Maureen McCabe's Art, the Medium Is the Message

The artist takes a mystical, magical journey through America's supernatural past in a retrospective at the Benton Museum of Art.

STORRS, Connecticut — Before scrolling their omniscient portable supercomputers, people looked to the stars to answer their deepest questions about the universe.

Then there’s Connecticut-based artist Maureen McCabe, 79, who remained spellbound by the sorcery of tarot card readers, carnival barkers, and voodoo priests for much of her life. Her mixed-media installations and collages exploring the origins of mysticism are the subject of an engrossing new retrospective, Fate and Magic: The Art of Maureen McCabe, at the University of Connecticut’s William Benton Museum of Art through December 14.

McCabe’s exposure to art began when her mother took her from their home in Quincy, Massachusetts, to the Museum of Fine Arts Boston for weekly art classes. She began to think about the intersection of cultures and was particularly fascinated by the museum’s medieval section.

“We were given paper and pencil and told to find something to draw,” McCabe said in an interview in the exhibition’s catalog. “We could go anywhere unaccompanied. I was drawn to the magical, the myth sculptures, and medieval relics. It all made sense to me.”

Her interest in the occult piqued in 1978, when she was on sabbatical in Paris from teaching at Connecticut College. McCabe encountered Jean-Paul Sartre’s 1943 screenplay Les jeux sont faits (The Chips are Down), in which two characters are given a second chance at love but realize they cannot escape their destinies, and started a series of assemblages exploring themes of fate and free will.

“With Maureen, everything she incorporates is always positive,” Amanda Douberly, curator and academic liaison at William Benton Museum of Art, told Hyperallergic. “There’s a lot in her work about protection. There’s nothing that’s harmful.”

Her early works, which included intricate drawings, toys, and other found objects glued onto vintage primary school slate chalkboards, resemble Joseph Cornell’s famous narrative compartments. But McCabe was also heavily influenced by sculptor Louise Nevelson, Cornell’s contemporary, as well as artists Remedios Varo and Leonora Carrington, who delved into ancient Celtic lore and featured priestesses and sorceresses as her protagonists.

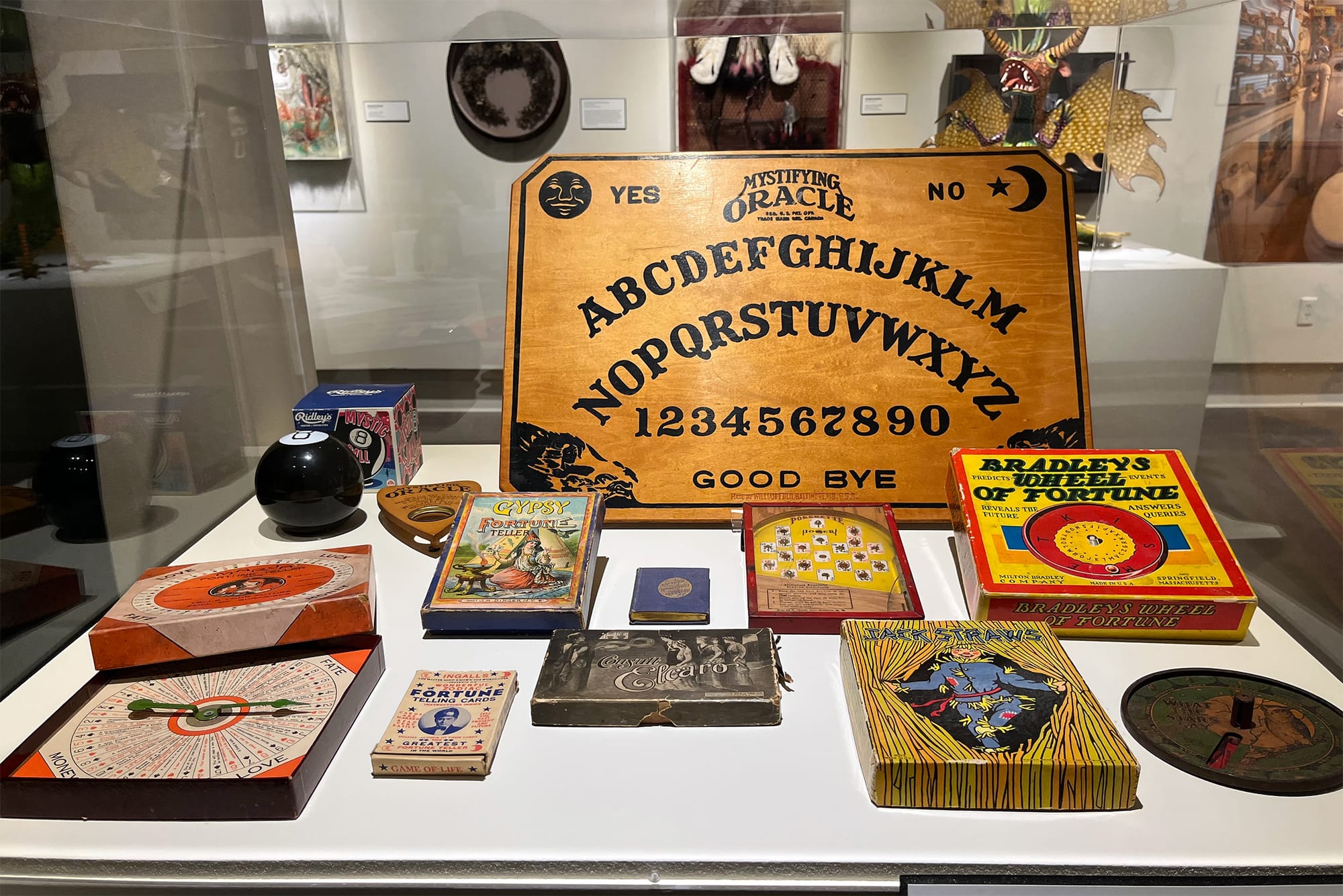

As her interests in mysticism grew, so did her collections. McCabe acquired vintage games, charms, crystals, feathers, magic powders, cards, and other turn-of-the-century tchotchkes from antique stores and eBay. Her studio in Quaker Hill, Connecticut, is filled with precious items organized horizontally salon-style along her walls (a large color photo of McCabe’s trinket-filled bathroom is included in the exhibition).

“She has enough good stuff in her studio, she could live another lifetime as an artist and still not make enough work,” Douberly said. “She’s responding to all these objects not just filtered through her own sensibility, but also current events.”

The most intriguing works in the show include a haunting series examining Ireland’s pre-Christian past, inspired by McCabe’s visit to prehistoric tombs and cairns; a vintage game board from Australia; and staged recreations of ancient myths that showcase McCabe’s eye as a director.

McCabe dedicated one mixed-media on slate work called “VOUDOU” (1993) to New Orleans’s Queen of Voodoo and the King of Voodoo, also known as the Chicken Man, whom she encountered in 1992. She found that her assemblage became far more complicated than she anticipated while researching voodoo spirituality in the Louisiana city.

“I wanted to be careful and accurate and do a positive job on this piece,” she said in a description posted next to her work. “I do not respond well to artists that are careless about incorporating powerful symbols in their work. I feel it is irresponsible and dangerous.”

The centerpiece of the exhibition is a four-foot-tall Irish Wishing Tree where visitors can take a green ribbon and make a wish while tying a loose knot on one of its branches. (This reporter wished for another dual national championship for the UConn men’s and women’s basketball teams next year.)

McCabe has also participated in several programs at the museum, making tarot cards based on the exhibition, discussing object performance with a puppetry professor, and talking with students about constellations.

“Women of her generation didn’t always have that consistent career recognition, and it’s just been a privilege to work on that longer story of her career,” Douberly said. “It’s important for artists at all levels of their career to present a life’s work. I hope we can do more of it.”