Indoor Migration: Dain, Aakash Nihalani & Peep-o-rama

This movement of art in- and outside has been of interest to me since I regularly began following street art about a year ago. The contexts in which the work can be seen often varies dramatically, and these environmental shifts raise a number of questions: does the work itself change as it traverses

I think it’s fair to say that graffiti and street art are pretty familiar to most New Yorker’s: appearing everywhere, in almost every neighborhood, both have a tendency to blend into their surroundings due to their ubiquity. Increasingly, street art exhibitions are also cropping up in galleries, though few people seem to be paying much attention — or critical attention, anyway — to street art’s migration indoors.

This movement of art in- and outside has been of interest to me since I regularly began following street art about a year ago. The contexts in which the work can be seen often varies dramatically, and these environmental shifts raise a number of questions: does the work itself change as it traverses public and private domains? If so, how? And what does this translation mean for our understanding of the work? A few months ago, I crisscrossed Brooklyn and Manhattan to investigate street art’s translation from the street to a gallery setting.

Dain’s Nostalgia

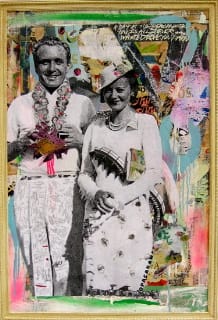

If you walked into the Brooklynite Gallery during Dain’s “Copasetic” show, you would have stepped into a world of nostalgia for a New York few of us remember but many probably know through film. Here the artist created an immersive environment reminiscent of 1940s New York. His colorful collages line the gallery walls while swing music plays to set the mood. His pieces were portraits, sometimes of movie stars like Liz Taylor and Betty Davis, or of everyday people, whose heads loom large and fill the frame of each piece. Around these black-and-white images, Dain adds colorful embellishment (often around the eyes of his figures) and further photographic elements, whether it be a torn image of the Cyclone from Coney Island or text lifted from a magazine. Each piece feels like an ode to a bygone era, or a cross-section of life in New York from 60 years ago. “All I Ever Wanted” (2009) shows a smiling couple surrounded by words and vintage images that reference sunny New York summers. Across the top of the piece is scrawled, “A day at the beach with you is all I ever wanted Love you DAIN.” Both sweet and melancholic, this piece begs the eye to search out a narrative, to determine the meaning behind these figures.

It was Dain’s first solo show and he is probably best known for his street art, which often simply consists of a black-and-white image of a famous face or a portrait lifted from an old yearbook. These works contain only a few additions of color or text, and his moniker often appears somewhere in the image. They are usually smaller, too, and have a much stronger graphic quality than the pieces included in “Copasetic.”

When I visited the Brooklynite Gallery, Rae McGrath who owns and runs the space with his wife, Hope, eagerly spoke about the differences between Dain’s work for the street and that seen in the gallery. With much enthusiasm for both the art and the artist, (the two men grew up together in Brooklyn) McGrath explained that Dain works with a distinct awareness of where each piece will ultimately end up. The street art pieces are created to have an immediate effect on a person walking by them, while the works seen indoors are highly detailed and require time to absorb. This shift in the artist’s creative process succeeds in producing captivating work that loses none of its impact as it migrates in- and outdoors.

Reflecting on Aakash Nihalani

Aakash Nihilani’s “Tapes and Mirrors” at Eastern District, (this time located in Bushwick) differed from “Copasetic” in demonstrating little to no awareness of the works’ translation from the street to the gallery setting. On Eastern District’s website they describe Nihilani’s work as “selectively place[d]…graphics around New York to highlight the unexpected contours and elegant geometry pre-existing in the city itself. All execution of his street level tape work is done on site, with little to no planning.” That is, he creates small disruptions in the public sphere by blocking off architectural elements of the cityscape with neon tape. I found nearly identical works at Eastern District where Nihilani uses two-dimensional “tape boxes” to demarcate space in the small gallery. Interesting configurations of the area result — in most cases emphasizing the architecture of the gallery itself within each composition. He drew attention to the intersections of walls and the floor, in a manner very reminiscent of Robert Smithson’s piles of stones and coral in corners of galleries. Like Smithson, Nihilani utilizes mirrors in his work as well. These reflective surfaces further complicate the architecture of the space and also situate the viewer within it. Unfortunately, this strategy of reflection seems rather derivative; see, for example, Olafur Eliasson’s Mirror Door pieces of 2008.

After visiting Eastern District I had to ask: how does work that aims to “highlight” overlooked aspects of New York’s architecture fare in the gallery context? What becomes of the aesthetic intention of these tape pieces when removed from their public environment? While Nihilani’s work creates unexpected visual delight on the street, few surprises are possible indoors. Confined within the white walls of Eastern District the work lost its playful spontaneity and left the gallery visitor hoping for more.

Peep-o-rama

On the final stop of my street art tour, I found myself next to the Westside Highway at 58th Street. Located on the ground floor of the Art Kraft Building are studios belonging to members of the Endless Love Crew and a gallery space (AK 57 Gallery) dedicated to street art and graffiti. During September, this latter space hosted a show, “Peep-o-Rama,” curated by El Celso, one of the founding members of the group.

Here, hung salon-style, were works by a variety of artists, though most pieces were generated by Celso, LA2 or Infinity, with some collaborations. The room felt pretty overwhelming, with so much stuff in it and seemingly little organization — in fact, I’m still not sure what to make of the title of the show, except to note the recurring nudes produced by Celso. However, luckily for me, when I visited El Celso, LA2 and Infinity were in their studios and all three eagerly spoke about their work. The visit consequently felt more like a day of open studios, but seeing any artist’s workspace and listening to him or her describe the process behind their art is always enlightening, and this time around their explanations made the trip worthwhile.

LA2’s work is reminiscent of Keith Haring — and for good reason. The two men worked together in the early 1980s and, as LA2 put, “I taught him [Haring] everything he knew.” Bravado and legend notwithstanding, the stylistic associations can’t be denied, though LA2’s work did feel very repetitive: the same thick, black, squiggly lines appearing on every surface (skate boards, tennis shoes and hoodies, in addition to the expected canvasses) surrounded by the artist’s tag. I actually found that LA2’s collaborations with other artists, in particular Celso, provided some of the most interesting work, as his designs lend a dynamic layer to the flat, graphic work aesthetic to which some street art tends to subscribe.

Celso’s pieces tend to be portraits of nude woman, often shown from the waist up. After you see the work once, his style is instantly recognizable, which means that his pieces, like LA2’s, feel repetitive in a gallery context. Celso’s work is much more striking and evocative on the street when one happens upon it, and it is another good example of the street context aiding the efficacy of this work.

Infinity’s pieces were the highlight of the trip, though most of what I saw of his were works in progress. The building’s “spray room” — the place where artists cover the walls with experiments in aerosol — included a large, simplified piece by Infinity and it included his usual arrangements of symbols and vaguely mathematical references. Tags from the usual suspects also made an appearance on the piece, underscoring the communal quality of the space — this room actually felt like it could be a forgotten alley, known only to graf and street artists as a prime spot for work. That sort of context for the work — where artists spray, paint or paste pieces that respond to works by other — seems to be the ideal space for street art, where a sense of community is generated.

Street art’s shift indoors has largely been overlooked by art critics, though it seems that the artists themselves could stand to pay some more attention to how their works translate when viewed in a private setting. Dain’s show was ultimately the most successful due to his palpable awareness of the gallery’s effect on his art’s reception. It seems that other artists would benefit from the same consideration, especially when such consideration obviously goes into the choice of a location for the works on the street. A stronger curatorial presence on the part of the artist would also go a long way in ensuring that street art’s move indoors is a productive shift.

Dain’s “Copasetic” ended October 10, Brooklynite Gallery, 334 Malcolm X Boulevard

Aakash Nihilani’s “Tape and Mirrors” ran from September 25 to October 25, Eastern District, 43 Bogart Street

Various Artists in “Peep-o-Rama” was on view during the month of September, AK 57 Gallery, 830 twelfth Ave