International Rendezvous at Guatemala’s Paiz Art Biennial

This year’s biennial, The World Tree, was intended to highlight the “archetypal myth central to many ancient cosmogonies.”

ANTIGUA and GUATEMALA CITY, Guatemala — Fall 2025 has been quite a busy time for Guatemala: The country hosted the 12th edition of the Central American Games in October, attempted to qualify for next year’s FIFA World Cup, and opened the 24th Bienal de Arte Paiz at the beginning of November. Indeed, this year’s edition of the second-oldest biennial in Latin America is its most ambitious to date, with work by 46 artists (almost double the number of 2023’s edition) spread across 10 venues in Antigua and Guatemala City and representing over 15 countries.

Taking inspiration from the myth of the tree of life, the idea for this year’s theme, The World Tree, is to present artistic practices and artworks that highlight the “archetypal myth central to many ancient cosmogonies,” as curator Eugenio Viola writes in the catalog. Closer to the event itself, the tree of life is fundamental to Mayan cosmogony, symbolizing the connection between different levels of existence and the structure of the universe. For Viola, artistic director of the Bogotá Museum of Modern Art (MAMBO), this myth perfectly illustrates how many parts of our society are interconnected.

The press preview, which I attended along with writers from publications across the Americas, started with a day in Antigua, where many of the presented works responded to the cultural and site-specific nature of the place. At La Nueva Fabrica, which has been partnering with the biennial for almost five years, we were welcomed by the team of the Fundación Paiz para la Educación y la Cultura, a nonprofit that has been fostering education and culture in Guatemala for more than 40 years. Artists, curators, and art professionals from all over the world convened for the introduction, but some tension emerged when the speeches were made in English, with Spanish translation offered through headphones. Some people were yelling at the presenters to speak in Spanish, noting that we were in Guatemala; why not offer English translation instead?

Moving on to the art at La Nueva Fabrica, I saw a number of strong installations, among them Patricia Belli’s “Multitudes” (2025), a suspended quilt composed of used clothing and lace. Belli assembles remnants of found materials in her work about destruction and repair, creating a new form to grant the material a second life. Another textile work, Luz Lizarazo's newly commissioned mural “Wander” (2025), which winds through the gallery, depicts animals and plants interspersed between representations of the earth and sky realms. Balam Soto addressed Mayan mythology directly with “Kukulkan: An Immersive Mythological Journey” (2025), a wall and floor video installation employing data interactivity and extended reality to translate the myth of the Mayan serpent deity into poetry and sensory language.

Our next stop was the Museo Arte Colonial, formerly the University of San Carlos. Old school benches, religious relics, and murals depicting past students’ graduations were scattered throughout the venue. Unfortunately, textile works by Gian Maria Tosatti and D Harding got somewhat lost in such a large venue due to their sparse installation, which also displayed pre-Hispanic archaeological Mayan art pieces, presented in collaboration with the Ruta Maya Foundation.

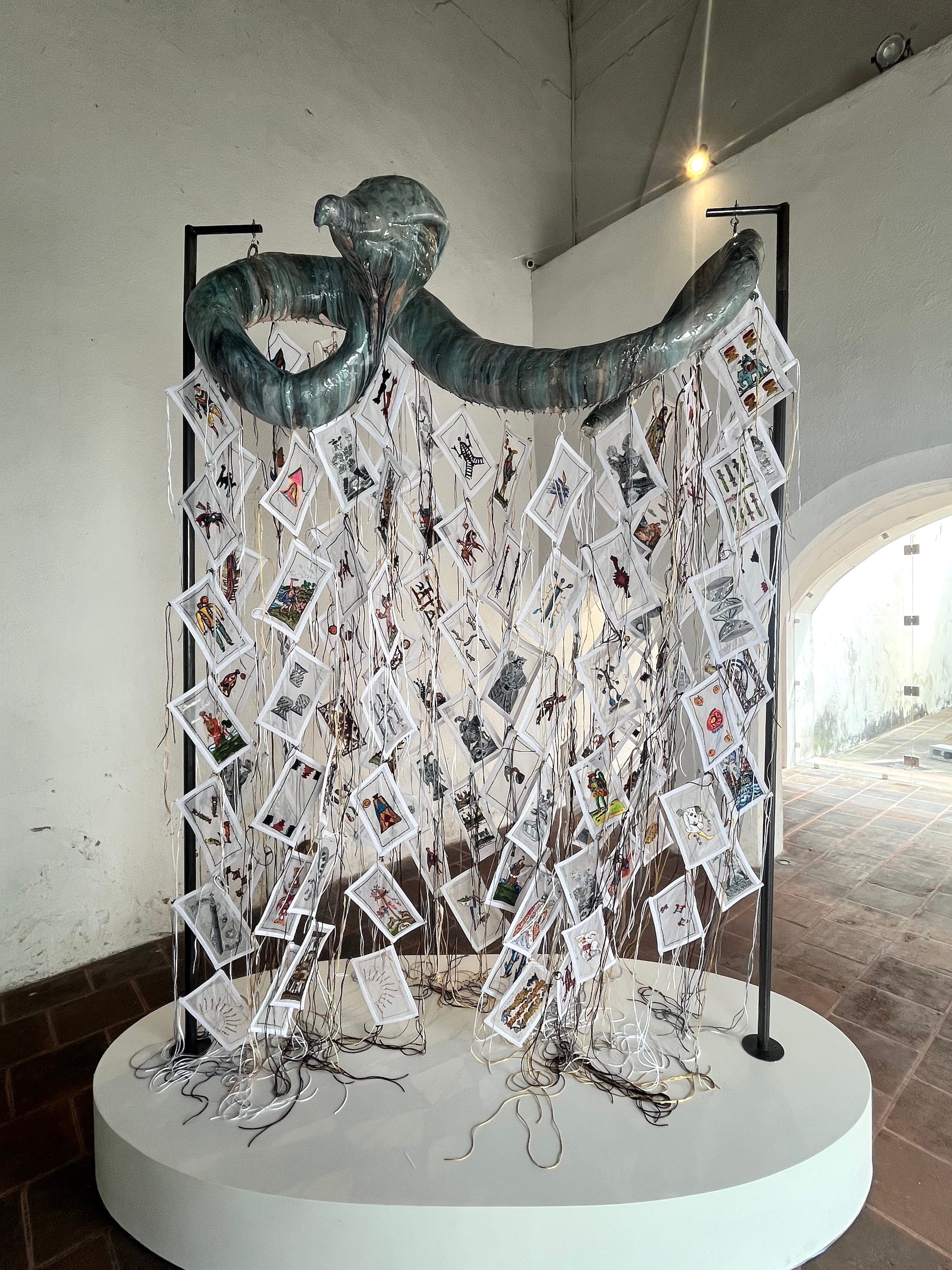

A short walk led us to the National Museum of Guatemalan Art (MUNAG), whose elaborate installations included Naufus Ramírez-Figueroa’s “From Spiral to Spiral,” a series of embroidered playing cards or “naipes” suspended from a large ceramic snake. The work merges the artist’s family lineage with European colonial history: While the women in his family used these cards for divination, they were a key income source for the Spanish Monarchy, the making of which was tightly controlled by the Crown, seeking to eradicate forgery and its use in gambling. Voluspa Jarpa’s “Extinction,” floor to ceiling tridimensional maps from her series Cartografías de la Sindemia, combines territorial maps, graphics, archival materials, and data sets to show that territorial memory is far more complex than historical memory, and that geopolitical boundaries are not as sharp as they appear on maps.

At the Centro de Formación de Cooperación Española, Antonio Pichillà incorporates the ritual of dance with the image of a stone to reconnect with Mother Nature: “Dancing with a Stone” offers insight into the syncretism practiced in Guatemala today. We arrived at the Convento La Recolección as the sun was setting; there, amid the ruins, Igor Grubić planted trees and Kite conducted violinists, performing dreams that were translated into scores.

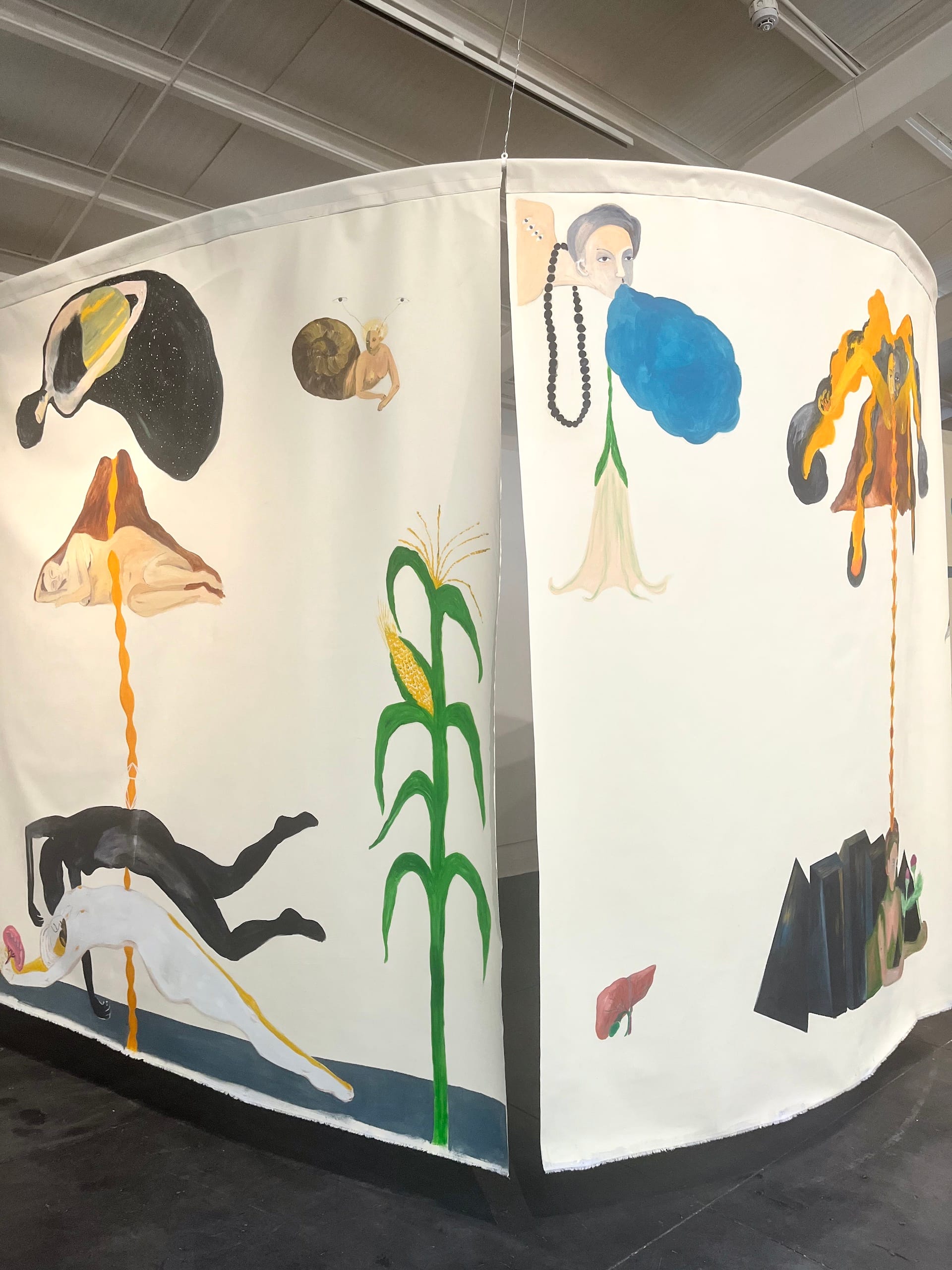

The next two days of the preview were spent in Guatemala City, where the rest of the biennial unfolded. Despite the World Tree theme, several of the works I saw were connected by language, attempting to translate knowledge, information, and elements to a universal tongue. Veronica Riedel transcribed Lake Atitlán into Morse code, while Adji Dieye transposed the importance of the triangle in Mayan culture and mythology with the African architectural fractal.

The biennial also featured a number of outstanding performances. Wearing José Rubén Zamora’s clothing, Regina José Galindo stood in front of the local courthouse building and read (in Spanish) a letter by the El Periódico newspaper founder detailing his violent treatment, censorship, and imprisonment by Guatemalan authorities. Zamora is currently still detained for alleged obstruction of justice, a decision that is yet to be proven. My Spanish isn’t fluent, but I understood enough to grasp what a risk Galindo was taking by speaking for him. The preview ended with Carlos Martiel, completely naked in the white cube of the new Fundación Paiz building, inviting the crowd to share the heavy weight of the word "Genocidio" forged in iron and held with chains.

Throughout the 24th Bienal de Arte Paiz, I encountered pieces that made significant and poignant statements on the current state of the world. Artists from outside of Guatemala or Central America established solid connections between their own personal histories or artistic practices and Mayan cosmogonies and histories. By spreading the event across multiple venues in two cities, the country itself becomes an integral part of the experience. If there were any issues that I sensed and heard around me, they were the general use of English, a colonial language, the small number of Guatemalan artists (six), the Eurocentric aesthetics like classical music, and the appropriation of the Popol Vuh, a sacred and foundational Mayan narrative, by an Italian curator.

For me, these concerns raised the questions: What are we looking for when visiting biennials that are “outside” of the main circuit? Are we expecting them to remain insular, speaking to and for their own population? They are, by definition, large-scale international exhibitions of contemporary art. No one is expecting the Venice Biennale’s curated exhibition to feature only Italian artists. Eugenio Viola skillfully brought together artists from around the world, with high caliber Guatemalan and Latin American artists, and presented an exhibition that admirably represents the interconnected relationships we have among us as humans, animals, and plants, and through ancestral and astral planes.

The world tree connects us all, its roots reaching even those who are the most disenfranchised and forgotten, those who endure catastrophes, massacres, incarceration, and genocides. As a curator who describes his practice as “writing chapters of an ever-evolving book,” Viola composed a story with which many people can relate.

The 24th Bienal de Arte Paiz, The World Tree, continues at various venues in Antigua and Guatemala City, Guatemala, through February 15. The biennial was curated by Eugenio Viola.