Propaganda at the British Library

As a way to guide public opinion to a collective obedience, governments around the world have employed art. These visual modes of propaganda can be powerful and moving, and they haven't disappeared, as proved by the playing cards showing members of Saddam Hussein's regime distributed by the US durin

As a way to guide public opinion to a collective obedience, governments around the world have employed art. These visual modes of propaganda can be powerful and moving, and they haven’t disappeared, as proved by the playing cards showing members of Saddam Hussein’s regime distributed by the US during the 2003 Iraq invasion. The British Library in London is opening an exhibition that examines extensively this tradition of control.

Propaganda: Power and Persuasion has a global focus on state-run propaganda that stretches back to the ancient world all the way up to contemporary Twitter and our current bank notes. One of the co-curators at the British Library, Jude England, stated in the release:

We want visitors to consider the role of propaganda in their own lives today, as well as look at the state’s use of propaganda throughout history. That’s why, as well as displaying iconic pieces of propaganda from the Library’s collections, such as posters from both World Wars, the Cold War, and Vietnam, we’ll also be focusing on more surprising examples, such as the 2012 Olympics and even Twitter – things you wouldn’t necessarily associate with a word like ‘propaganda’.

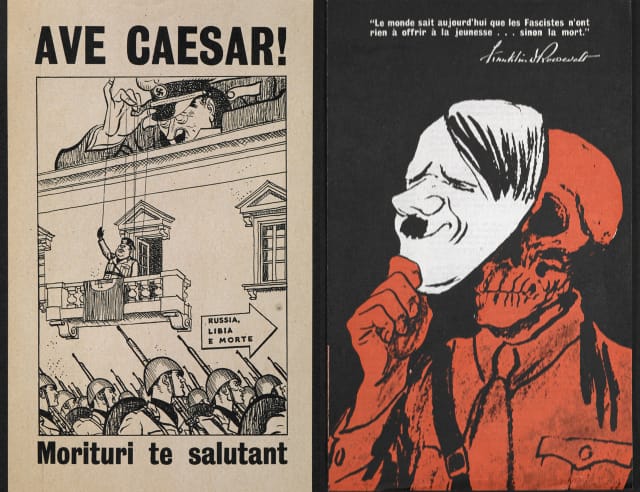

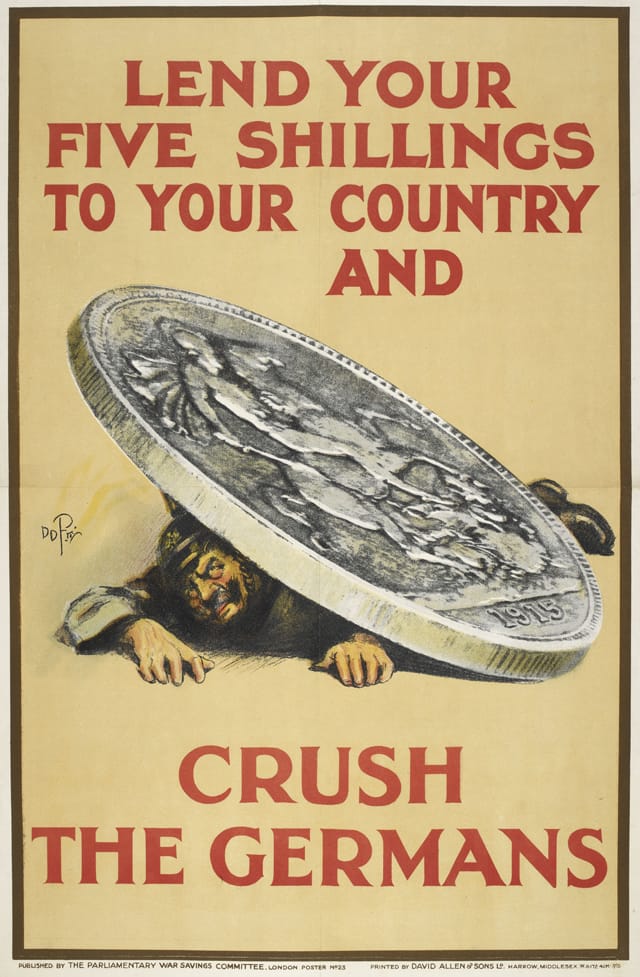

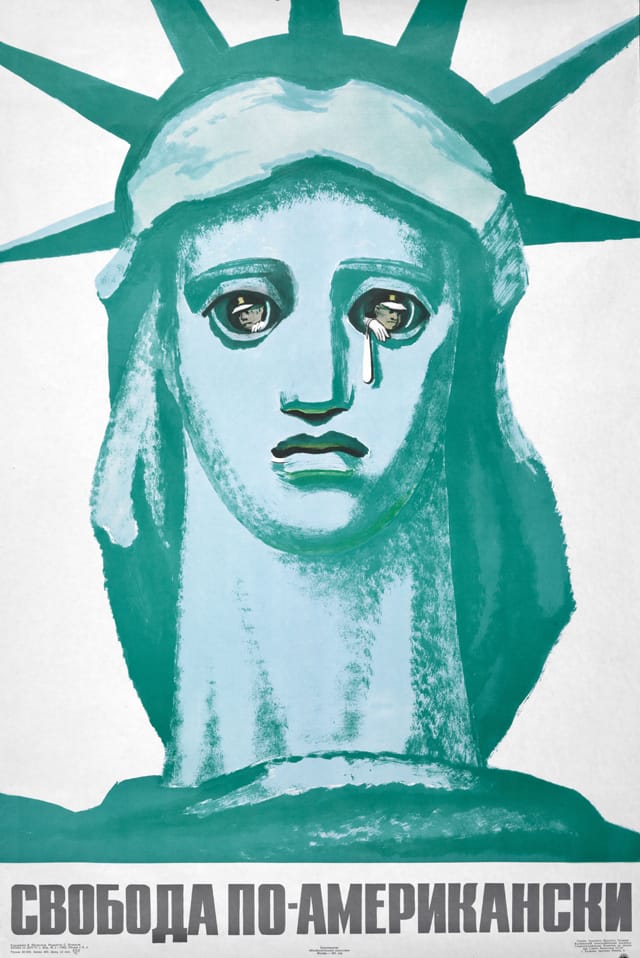

With about 200 items, there’s plenty of examples of how war posters preyed on visceral reactions to death and destruction, and how the icons of a nation can be manipulated into calls to action or reaction. Yet while images like Hitler removing a mask to show a skull (illustrated by FDR’s proclamation that “the world knows that the Nazis, the Fascists, and the militarists of Japan have nothing to offer to youth, except death”) are expected fodder for any propaganda showing, there are also grand portraits of leaders like Napoleon, toweringly painted by Jean-Baptiste Borely and decked out from silky shoes to golden laurel crown. Despite its ostentatious opulence that shows him secure as emperor, it was painted as his power was declining to his ultimate defeat at Waterloo.

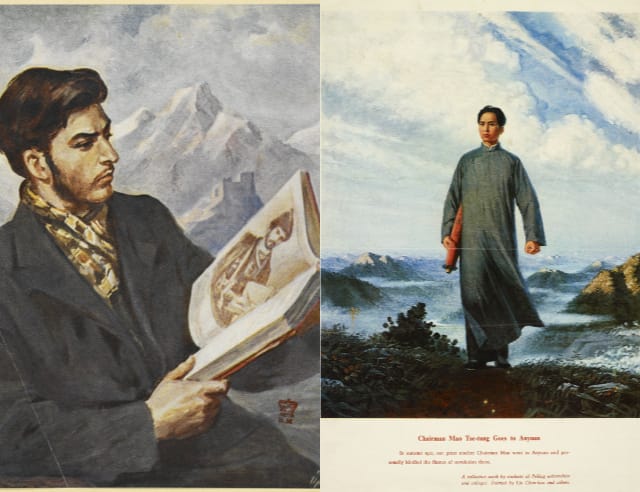

Similar and subtle in using portraiture to influence a desired profile are the images of Mao and Stalin, both showing them in an idealized youth. While nothing on them blares COMMUNISM IS THE WAY, they suggest with simplicity the visions of perfection of the leaders.

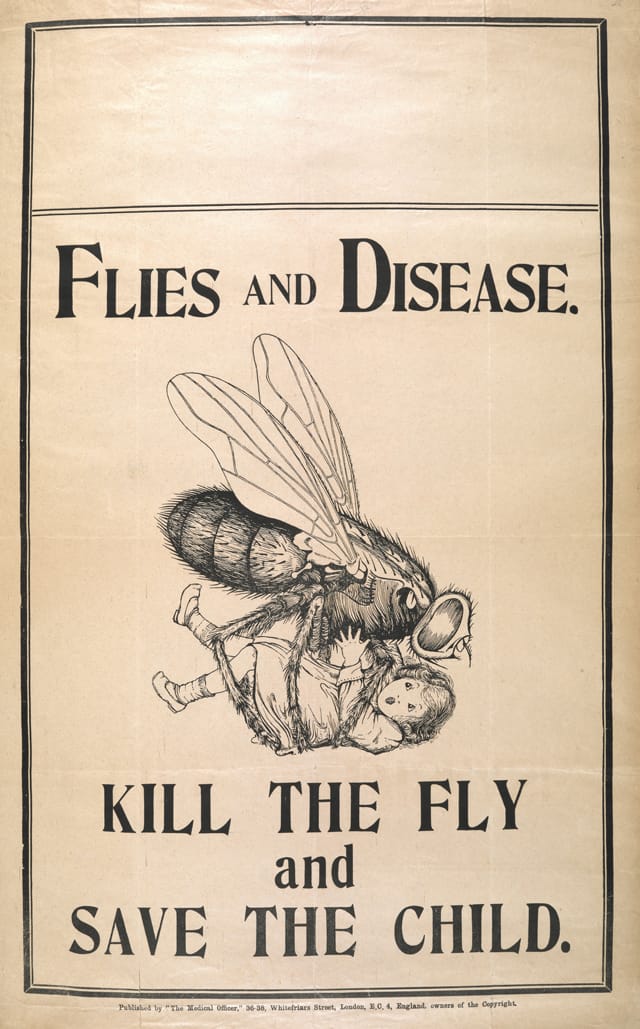

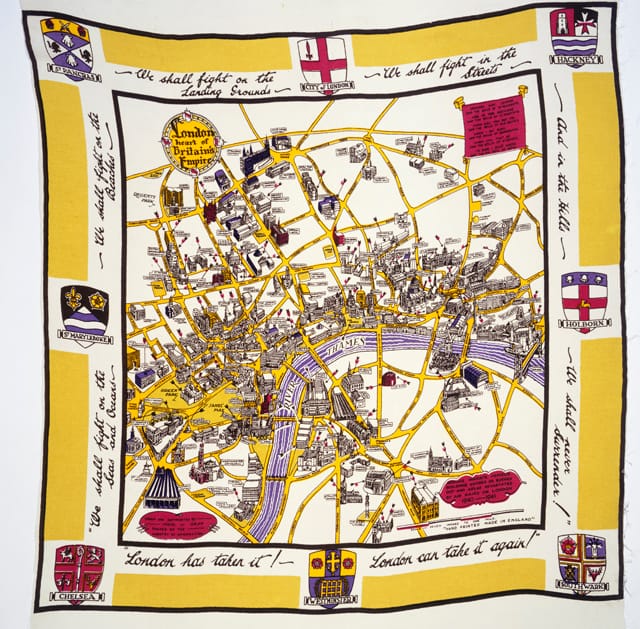

All of this is just the beginning of a delve into propaganda, as it is an always present component of our visual culture. Some of the most significant events of our recent history have resulted in state-funded art meant to blare out from the noise of daily life and drive their messages straight into your heart. When the Lusitania was torpedoed by a German U-boat in 1915, propaganda posters showing drowning women and children and a smoldering ship, demanded viewers to “take up the sword of justice.” When the space race consumed the US and Soviet Union in an epic, and expensive, battle for the stars, even the pioneering space dogs were honored as Soviet conquerors of the cosmic sphere. Art is, in a way, all about persuasion already, convincing a viewer of an artist’s world perception, even in the most passive of work. It’s a power that governments around the world have long appreciated for its influence on our emotional cores.

Here are some more views of propaganda, past and present, from Propaganda: Power and Persuasion:

Propaganda: Power and Persuasion is at the British Library (96 Euston Road, London), May 17 to September 17.