Killed By the State

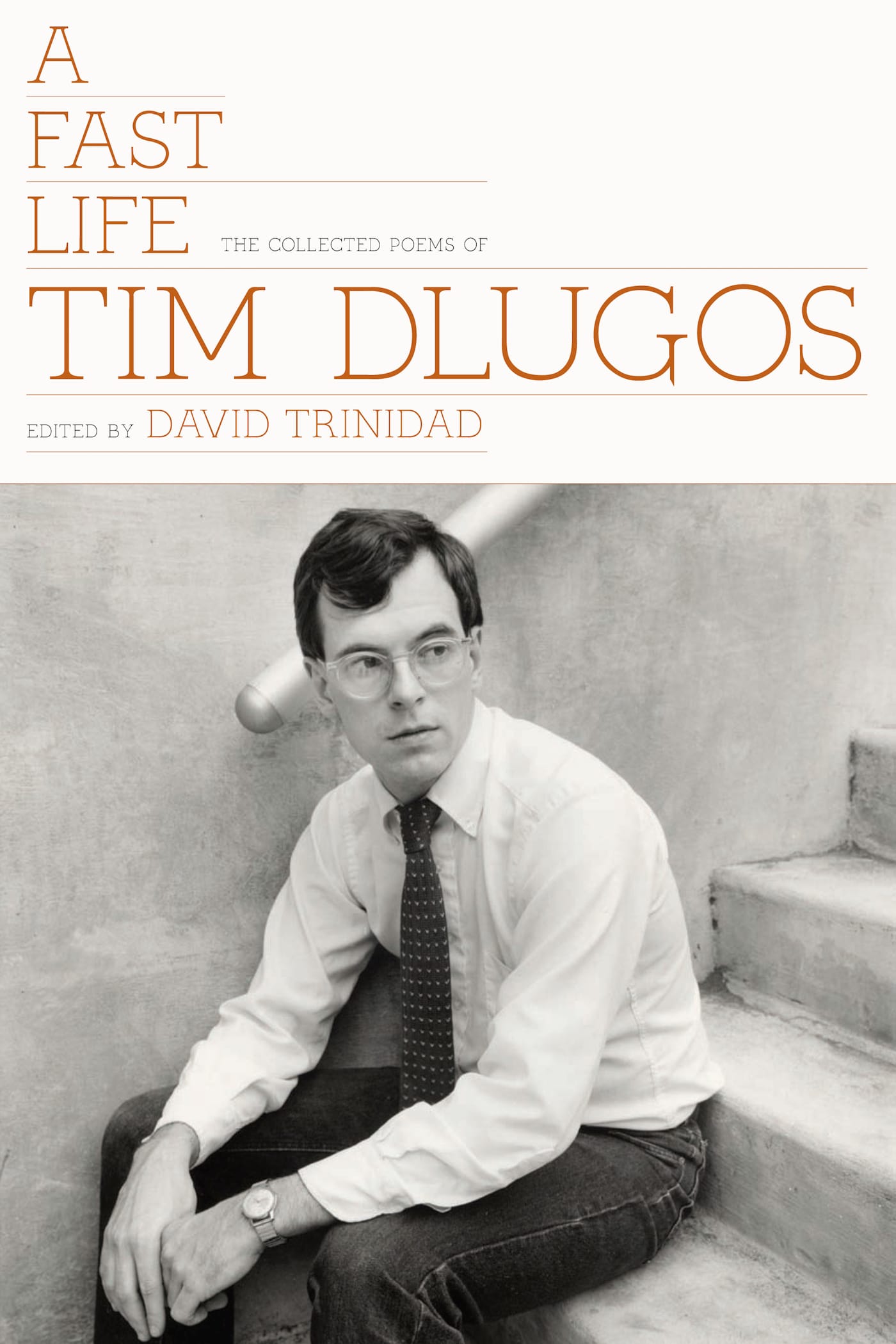

A few weeks ago, while I was reading In the Empire of the Air: The Poems of Donald Britton, edited by Reginald Shepherd and Philip Clark, I was reminded of A Fast Life: The Collected Poems of Tim Dlugos (2011), edited by David Trinidad. This happens with poetry – one poem or book leads to another, l

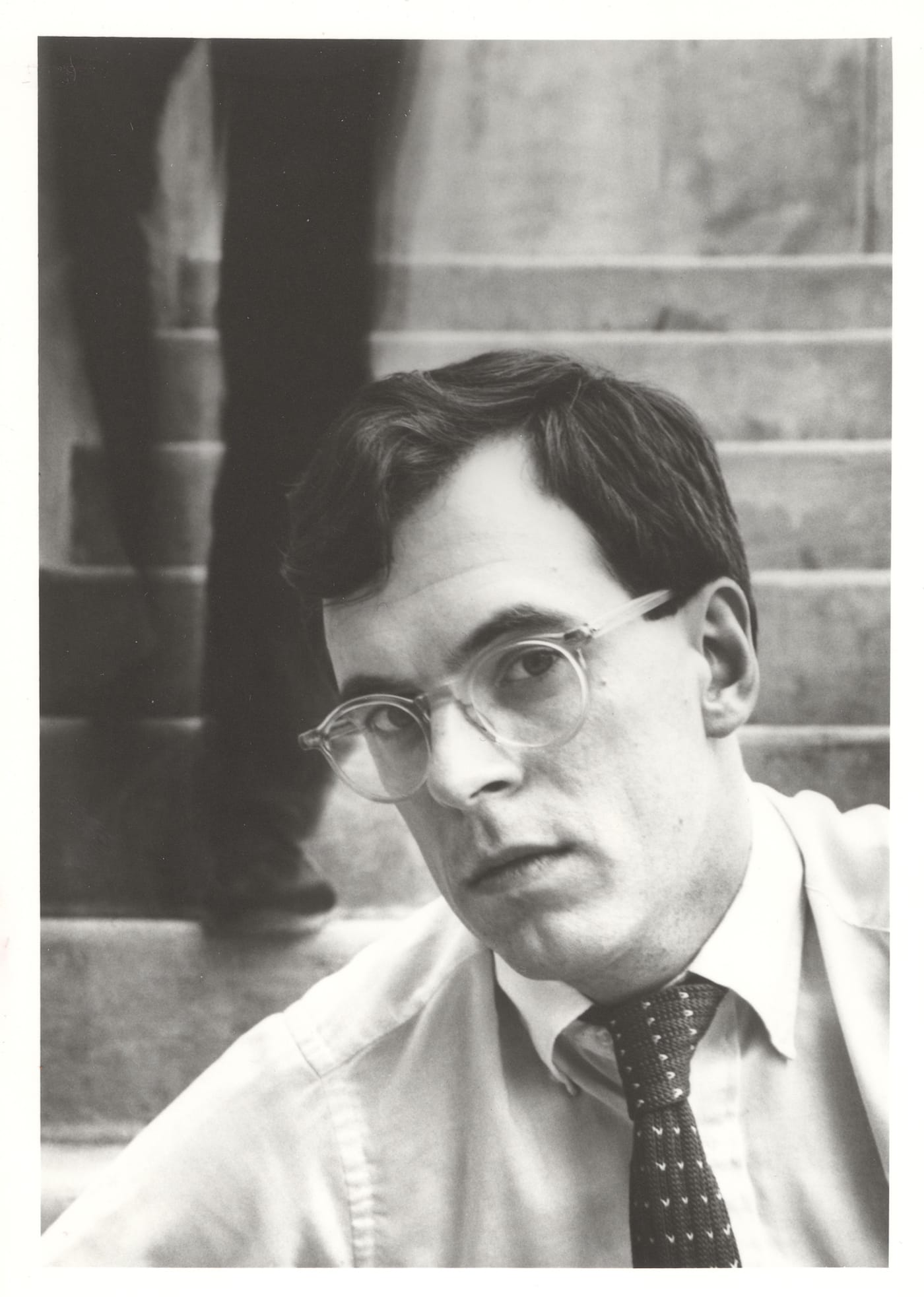

A few weeks ago, while I was reading In the Empire of the Air: The Poems of Donald Britton, edited by Reginald Shepherd and Philip Clark, I was reminded of A Fast Life: The Collected Poems of Tim Dlugos (2011), edited by David Trinidad. This happens with poetry – one poem or book leads to another, like a chain letter. Britton and Dlugos were friends, but their writing could not be more different. For one thing, Britton’s selection amounts to less than 100 pages, while Dlugos’ is over 600. Ted Berrigan called Dlugos “The Frank O’Hara of his generation.” The comparison is both apt and beside the point. Dlugos’ poems need to be read for what they are, indispensable testimony of an age and time.

Without dwelling on the biography, which can be gotten from Trinidad’s “Introduction” and “Chronology,” it is enough to say here that Dlugos (1950 – 1990) and Britton (1951 – 1994) were good friends, and that Dlugos dedicated the poem “Qum” to Britton. Both died of AIDS or, as Douglas Crase correctly writes in his “Afterword” to Britton’s In the Empire of the Air:

We say ‘died,’ but of course they were killed, by a threat they could never have foreseen.

Trinidad usefully divides the poems into the cities where Dlugos lived: Philadelphia, 1970-1973; Washington, D. C., 1973 – 1976; Manhattan and Brooklyn, 1976 – 1988; New Haven and Manhattan, 1988 – 1990. In twenty years, the reader goes from the exuberant disclosures of a young poet absorbing Frank O’Hara’s dictum, “I do this, I do that” to the poems written after he tested positive for HIV (November 1987) and began studying at Yale Divinity School, with the intention of becoming a priest in the Episcopal Church.

According to Trinidad’s useful chronology of Dlugos’ life, after two tyears writing “sporadically” from 1985 until 1987, he began writing “regularly” in 1988.

Dlugos’ last poems amount to a diary of a man who learns that he is under a death sentence. For all of their personal revelations and close observation of his life and those around him, Dlugos’ poems are on the opposite end of the spectrum from the so-called confessional mode of Robert Lowell, Anne Sexton and Sylvia Plath. The poem “Powerless,” which is about going to his first AA meeting and much else, begins:

I was a mess. I felt like crying

all the time.

At no point does Dlugos ask for our sympathy. In fact, despite hitting bottom, there is a warmth and humor to the poem:

I made a call and went to my first

meeting a few blocks away. I’d been wondering

where all the healthy, handsome people

in West Hollywood had disappeared to.

I found out. An old guy

with a shaven head and twenty years

spoke first.

If Dlugos ever steps out of the poem, it is to recollect passion not in tranquility but in a lucid fever that ought to burn through any aesthetic objection you might have (“Too New York School” or “Not experimental enough”) unless, of course, you need to cling to those ideals to get through the day. Dlugos learned to let go of everything. In the poem “No Voice,” we read:

You made pissing away

your gifts look like an art form,

but striking a profile

with your arm akimbo

on the moving sidewalk headed

toward the precipice cheapens

every death, not just your own.

Dlugos uses the vernacular to apprehend the figure he is describing. There is no reliance on metaphor, no extravagant gesture or knowing aside. Such directness comes from William Carlos Williams. It looks easy, but it isn’t. What’s not apparent is how much Dlugos has cut away as he moves smoothly from one perception to another. “No Voice” ends:

Scarecrow, genius, major

minor artist and the keenest

critic of your brief day: it’s no faux pas

to want to stay.

Dlugos did not romanticize suffering or death. He was a poet, a homosexual, and a political and social activist. But he did not consider himself to be a special case and would never compare himself to a Jew being sent to “to Dachau, Auschwitz, Belsen” as Plath did. In the poems he writes in the last two years of his life the reader will come across “Radiant Child,” which was written on February 16, 1990, the day Keith Haring died of AIDS at the age of thirty-one.

A baby in a desert

boom town wears a T-shirt

on which is an image

of the Radiant Child.

The infant is no larger

than a young man’s hand,

the generous hand of the artist

who died this afternoon.

By the time she’s old enough

to crawl like the child

in the drawing, his hand

will wear a coat of dust,

or long ago have been

reduced to ash. Ashley

Noel Snow, my lover’s niece,

a brand-new life in a T-shirt

from the Pop Shop, in a snapshot

he would have loved to see.

The pared down vernacular that Dlugos got from O’Hara and Williams is always linked to immediate, everyday perceptions filtered through a particular consciousness; it is evidence of his engagement with the present, fully aware that he has little time left in this world. It is this directness, which was present in his work from the beginning, that remains fresh. We read the poem and hear his voice. The poet is in the room with us, speaking in a soft, unprotected voice. There are no rhetorical flourishes, no attempts to impress us with his knowledge or experience.

In “Signs of Madness,” Dlugos writes:

Recognizing strings

of coincidence as having

baleful or hermetic meaning,

e.g. the fact that each

of Ronald Wilson

Reagan’s three names has

six letters, Mark of

the Apocalyptic Beast,

languorous and toothless

though it would have to be

to fit that application.

This is how Dlugos characterizes Reagan, who did not acknowledge the AIDS epidemic until May 31, 1987, six years after the first cases had been reported. He may be the Apocalyptic Beast, but he is also lazy and toothless.

In the late 80s, after Dlugos was diagnosed HIV positive, he remembers the literary critic David Kalstone, whose apartment on West 22nd Street he visited “on a winter day/in 1976” and a book he borrowed and never returned. Ten years later, in 1986, Kalstone died of AIDS at the age of fifty-three. In his masterpiece – what else to call it? – “G-9,” Dlugos writes:

My first time here on G-9,

the AIDS ward, the cheery

D & D building intentionality

of the décor that made me feel

like jumping out the window.

No matter the situation, Dlugos remains open to his feelings of vulnerability and never tries to step away from them. “D.O.A.,” the last poem Dlugos wrote before dying of AIDS three months later, and the last poem in the book, should be required reading in every literature class.

A Fast Life: The Collected Poems of Tim Dlugos (2011) is published by Nightboat Books and is available from Amazon and other online booksellers.