Let's Spend the Weeknd Together

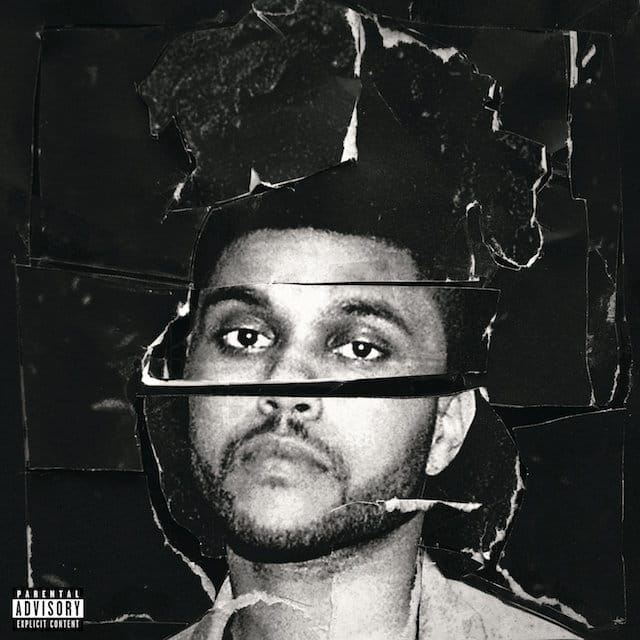

Abel Tesfaye’s new album, Beauty Behind the Madness, cements the former indie/DIY/Internet mystery man’s newfound commercial clout.

From his lilting, honey-soaked voice to his glittering, textured dancebeats, from his grandly tragic melodies to the sweeping waves of keyboard that carry them, from the way he licks his lips during orgasm to his killer pout directly afterwards, electro-R&B singer-songwriter and/or pinup idol Abel Tesfaye d/b/a the Weeknd is the true postmodern loverboy, our own millennial Casanova, Prince Charming with a noose tied tight around his genitals. No other artist topping the charts right now has fashioned a come-on so enticing yet eerie, so sleazy yet irresistible. Forget Drake, who has recently abandoned his romantic confessional mode and become a real rapper; disregard for the moment Justin Timberlake, whose tuxedo-clad smarm recalls male sex roles that predate the dawn of the early crooners. Tesfaye’s fashionably conflicted relationship with what some call hookup culture, so sleek and stylized and sentimental in its back-and-forth zigzag between pleasure and pain, makes him the only role model any young heterosexual male navigating a big bad world of wealth, drugs, strippers, and Instagram needs.

Tesfaye’s new album, Beauty Behind the Madness, cements the former indie/DIY/Internet mystery man’s newfound commercial clout. Having captivated critics, electronica obsessives, and pop aesthetes eager to expand their musical horizons all throughout 2011, when he released three whole albums for free online, he became a recognized star gradually—like many artists who become popular via the Internet, initially he obscured his identity as a means of standing out from the crowd, avoiding interviews and hiding his face to cultivate mystique. But pretty soon he was touring, meeting fans in person, and collaborating with established superstars (see Drake’s “Crew Love,” a Drakeless version of which Tesfaye likes to perform live), and in 2012 he signed with Republic to officially release his three 2011 mixtapes on the market, in a big box set called Trilogy. His first commercial studio album, 2013’s Kiss Land, sweetened and smoothened what used to be a grim, spare formula, and Beauty Behind the Madness does the same, especially with Swedish teenpop king Max Martin spraying magic tuneful jingle polish over the whole thing. Hardly a departure sonically, dominated by the same kind of creepy-crackly keyboard he always specialized in, Beauty Behind the Madness makes its pop move with songwriting catchier and more simplistic than Tesfaye’s norm, songwriting that irons out the complexity and reduces observation to generalization, taking a persona once framed as an antihero and calling him a heartthrob.

Although the Weeknd possesses his own dark musical signature, a spare, ominous style of buzzing electrobeat suggestive of back rooms filled with cigar smoke, long night drives in luxury cars, the scariest and most jaded imaginable noir, it was by playing a character suited to such music that he first captivated his fans. Heir to a long tradition of psychopathic glamourboys in popular music tracing back to Steely Dan’s Gaucho, he’s a playboy extraordinaire: calmly floating through pool parties with a bored, dead look on his face, strung out on more drugs than anyone should consume in a lifetime, falling into bed with girls whom he’d really like to love but he knows he won’t remember in the morning. The basic rhetorical trick of this music is to first provide a rich, overwhelming, nearly nauseating impression of scandalous Hollywood opulence (Tesfaye is Canadian, but he’s in the tradition), material luxuries about which most people can only fantasize, and then to declare such fantasies empty. He’s living the good life, moans he, and he’s miserable; he’s the quiet, sullen kid in the corner, staring off into space and moping about the surrounding party’s meaningless decadence. He addresses his songs to a revolving panoply of women he feels guilty for leading on and knows he’ll disappoint by picking his lifestyle over them; often his tone is regretful, penitent (if only he hadn’t abandoned his baby to go take part in that basement orgy, he sobs with clenched fist, forlornly tucking his Hermès tie into his Gucci belt). The music’s grand, cold, halting, shiny surface, not to mention his voice — a high, sweet, fragile thing, whose tenderness feels weirdly displaced in this alienated context, marking him simultaneously as erotic R&B paramour and sensitive dreamer lost in his feelings — fit this image exactly. And unlike the ostensibly similar Frank Ocean, who observes the same world from the outside with a journalist’s eye, or Lana Del Rey, who subsumes her California-noir imagery into a larger evocation/critique of the American mythic female, Tesfaye really seems to wallow in the projected glamour of his art as shamelessly and immaturely as a frat boy taking his first sniff of cocaine.

Having scored two number one singles this year (and there may be more), Beauty Behind the Madness certainly qualifies as a well-crafted, professional collection of hooks and choruses; its mastery inheres in the way “The Hills” turns sampled background shrieks into fabulous sound effects, the way “Acquainted” glides over shrewdly pitched percussion, the way his songs play with the same melodic signature to build tension. Nevertheless, the commercialization of what was once an edgy avant-garde style has been a disaster. While sticking to Tesfaye’s trademark electronic crunch, sharp keyboard rays glinting through a seeping wall of static, the music has lightened considerably: the keyboards have turned sufficiently clean that at times they’d sound acoustic if they weren’t so perfectly aligned with the drum machine, and in general the beats have gotten faster, more buoyant, more radio-adjusted than the slow burners he used to wail. “Losers” and “Earned It” (he donated the latter to the Fifty Shades of Grey soundtrack — of course he did) appropriate standard-issue EDM synthesizer breakdowns, and “Often” foregrounds those squeaky chopped-and-screwed robot voices that are always popping up in alternative-identified dance music. His voice remains disconcertingly soft and affectionate; his melodies, now simpler and traditionally catchier to complement the speedier beats, lend the music a brisk, light quality, so that while remaining formally similar to his earlier work, Beauty Behind the Madness plays above all like a pop record. Musically, this is an advance — it’s a pleasure to hear such arty electronic beatcraft demonstrate the straightforward functionality and disciplined formal expertise required for getting on the radio, and the many hummable if somewhat disconsolate tunes build on each other quite thrillingly, with the magnificent “Angel” providing catharsis at the end. But Tesfaye’s shtick can turn silly even at his most conflicted and psychologically complex (try “Wicked Games” or “What You Need” or “The Birds Pt. 1”), and the corporate slickening applied on Beauty Behind the Madness further eats away at the moral conscience of a character who already delights in reminding you of his shortcomings. There’s no longer any distance between himself and the macho creep he used to tiptoe around — if you think rappers are arrogant, wait until you hear this sensitive crooner telling his female conquests how lucky they are that he even noticed them, let alone selected them for (what an honor!) exclusive participation in a One Night Stand with the Weeknd Himself. In this context, the crisp, glossy, haunting music turns sour, all but indistinguishable from the shallow Hollywood danceschlock in whose shadow Tesfaye evolved, curdled by the rotting smell of hedonism left in the sun too long.

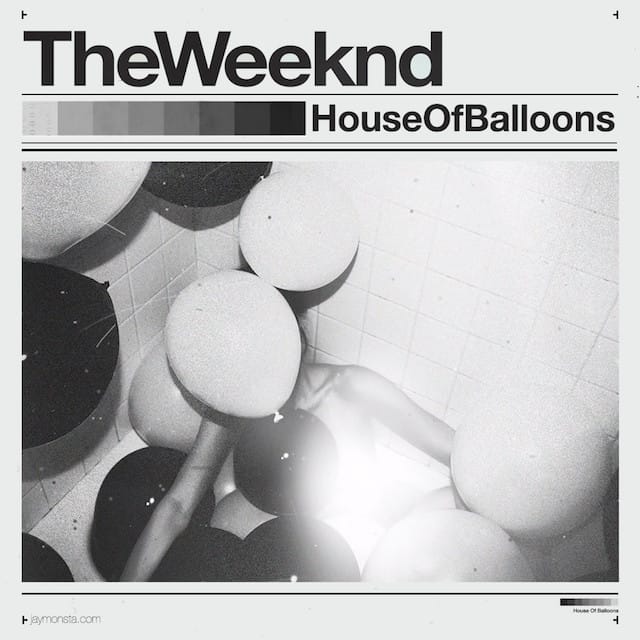

Theoretically, Tesfaye’s music maps out a dialectic between numbness and feeling. His immersion in an obscenely luxurious lifestyle has desensitized him to its pleasures, a process he’s aware of and perversely enjoys — and to which, in turn, he gradually becomes immune, and so the cycle proceeds ad infinitum. That’s how his very first mixtape and finest record by popular acclamation, 2011’s House of Balloons, worked: songs like “Wicked Games” and “High for This” laid out this psychological trap clearly, coldly, with the impending sense that the consequences of such self-destructive behavior would soon return to bite him in the ass. Almost by definition, Beauty Behind the Madness couldn’t possibly convey a character sketch so compelling, because its very existence — the fact that the Weeknd is still around, four years later, making his pop move — means that the self-destructive behavior has worked for him against the odds. Having gained a loyal fanbase by singing seduction songs through the voice of a disturbingly seductive character, Tesfaye quickly figured out that what people liked about the character wasn’t his indictment of New Hedonism but his embrace of its glamour and sex appeal, and Beauty Behind the Madness reflects this; he has internalized and epitomized the ethos he once critiqued. He gets to fuck around and brood about it afterwards (thus making it okay), he gets to be the playboy and the sadboy simultaneously, he gets to have his cake and eat it too. Who wouldn’t envy him and/or find him attractive? He’s sexy as hell, a scary erotic fantasy personified and taken to its extreme. House of Balloons functioned as an exposé of said fantasy, displaying it straightforwardly in all its stark power. Beauty Behind the Madness more closely resembles an unexamined celebration. Whether you envy him or fancy him, whether you identify with him or feel his torment warrants mothering, whether you fantasize about inhabiting his skin or letting him degrade yours, every childlike, sugary note he sings on the album drips with the calculation of a predator.

Compare 2011’s “Wicked Games,” the creepiest, most depraved song on House of Balloons, and 2015’s “Can’t Feel My Face,” the number one hit and alleged Song of the Summer that will eventually take Beauty Behind the Madness multiplatinum. Tesfaye’s signature tension between hedonism and anhedonia slithers through “Wicked Games” with a sly, knowing wink, slowly looping synthesizer shudder and the eerie trickle of raindrops around an ominous progression of arpeggiated guitar chords as the chorus builds: “Bring your love baby I could bring my shame/Bring the drugs baby I could bring my pain/I got my heart right here/I got my scars right here,” he cries, before grinning and singing, “Just let me motherfuckin’ love you”. “Can’t Feel My Face” addresses the same issue; “I can’t feel my face when I’m with you/but I love it” neatly sums up his dilemma. In fact, there’s something a little too neat about the whole song, from the controlled tempo to the exacting melody, from the sublime buildup before the chorus to the actual chorus’s lightweight anticlimax. The song’s stark command is cold, cerebral, detached, easy to admire and impossible to love. Hedonism has been dropped from the equation, it seems. Call the doctor, anhedonia has taken over. He’s losing feeling, he’s losing feeling, he’s losing feeling. He’s too far gone.

Beauty Behind the Madness (2015) and House of Balloons (2015) are available from Amazon and other online retailers.