Literature and Publishing in Developing Contexts

I was recently sent an article about the potential of e-books in developing countries. It's one year old, but with the rise of e-books and the growing popularity of Kindles (including on airplanes taking off and landing), it seemed worth revisiting.

Ask any immigrant family living in the United States who travels back often to their country of origin, and you’ll no doubt hear stories of the goods they bring back and forth. They might carry a new gadget or medical device from the US and on the way back they might bring a cultural souvenir or something else that reminds them of home. Diaspora networks play a vital role in economies for moving both objects and ideas across continents. Books have always been a part of this, as the law and economics of publishing often restrict where books are printed and distributed.

I was recently sent an article about the potential of e-books in developing countries. It’s one year old, but with the rise of e-books and the growing popularity of Kindles (including on airplanes taking off and landing), it seemed worth revisiting. While many in industrialized countries bemoan the death of print, print books have always been difficult to come by in developing nations, including in Africa. And while that means, as a matter of course, that there’s also less reading as a result, the growing popularity of e-books has shown that that problem laid mostly in distribution, rather than lack of interest.

“This is the counter-narrative to the idea that Africans don’t read,” the article noted. “Give people stories they can identify with and get them distributed more easily and things will change.” It went on to explore some of the technologies emerging to solve this distribution platform. biNu, for instance, puts e-reader content in the hands of feature phone users, while Bozza is a community of creatives in Africa. Blogs, Facebook groups, and other online platforms are creating new avenues for publication (and consumption) that don’t involve print.

A recent post from Ugandan writer Ernest Bazanye addressed the perception of Uganda and East Africa as a “literary desert.” Bazanye pointed to how new technologies and social media are opening the floodgates to poets and short story writers to build new communities and share their work. He made the distinction that the country is a “literary jungle,” while the local publishing industry is more desert-like. While discussing the economics of publishing, he also pointed to the history of poetry and literature, which started as a spoken tradition, shared amidst friends or on stages.

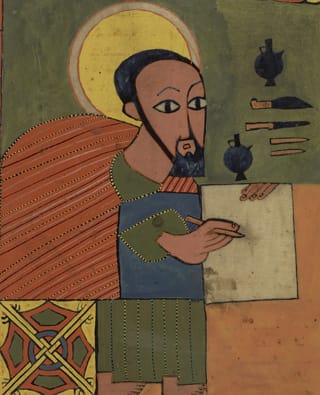

“The literary jungle is a publishing desert, but this is not necessarily a bad thing,” he wrote. “The language arts survived for millennia before Gutenberg’s gadgets came to Africa and now they are just going back to the way they were, the African way, if you will.”

Bazanye tells this story from an African perspective, but it’s important to remember that so many literary traditions, from Homeric odes to Shakespearen sonnets to Japanese tanka to Chinese folk ballads began with oral traditions. In this regard, print media are a blip in the long tradition of literature. There might be less print, but there are countless more stories and literary forms being explored now.