Long Road Outta Compton

Dr. Dre has been coasting on myth for so long that the success of his new album comes as a genuine surprise.

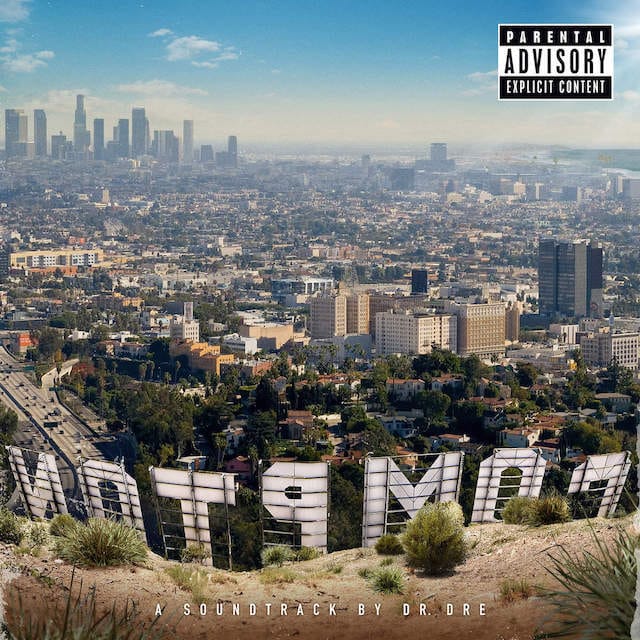

Dr. Dre has been coasting on myth for so long that the success of his new album comes as a genuine surprise. Not its commercial success per se — given the sheer amount of marketing behind the thing, not to mention the deference typically granted its auteur, the album was bound to move units, and has already gone gold. Nor does its critical acclaim perplex, for pretty much the same reasons as above. But Compton’s artistic success, as a smashing collection of beats and a coherent statement on celebrity and race in America, lends credence to his reputation as a perfectionist and suggests that he wasn’t just twiddling his thumbs during the sixteen years since his last album. When those searing waves of serrated synthesizer heat on “Talk About It” come charging out the gate, the message is clear: Dre’s back, and he has something to say.

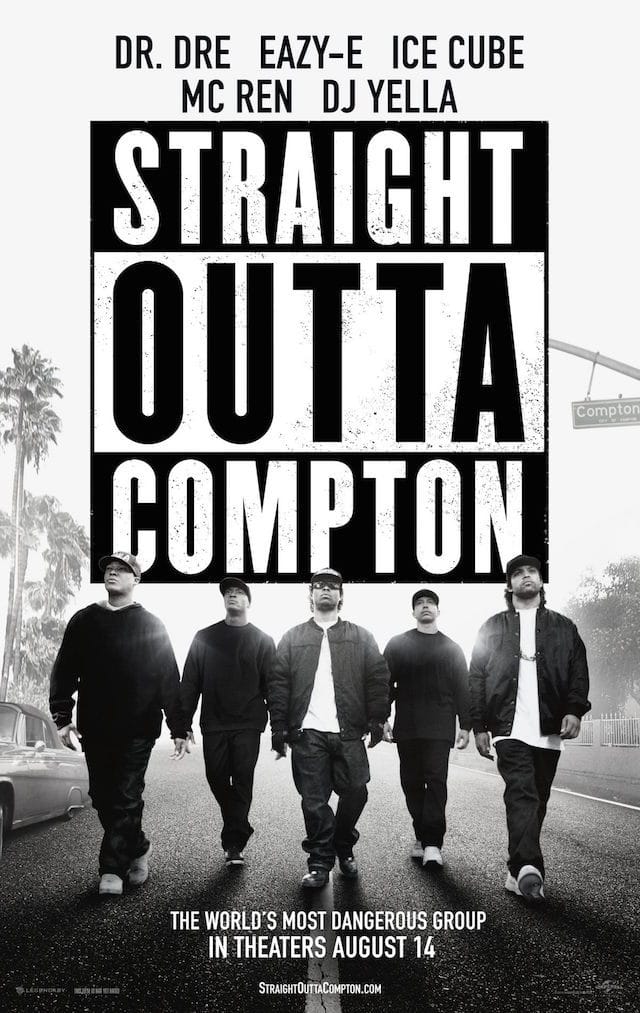

Compton, out since August, serves as a companion piece to F. Gary Gray’s N.W.A. biopic and/or origin fable, the confusingly titled Straight Outta Compton (named for N.W.A.’s 1988 debut). Having labored over an album called Detox for years to follow up 1999’s confusingly titled 2001, Dre allegedly felt his creative energy return while working as a producer on the movie, watching actors perform what’s probably an idealized version of his legendary hip-hop collective’s story and deciding he finally had to make some new music. So he scrapped Detox and started over, eventually releasing Compton just a week before the movie came out. Dre claims Compton will be his last album, and I believe him; as both owner of the Aftermath label and CEO of Beats Electronics (the latter bought in 2014 by Apple for $3 billion), he’s too busy an entrepreneur to work as a full-time rapper. Concomitantly, Compton sounds like a valedictory: it’s big, bombastic, bloated to the gills with guest rappers, singers, divas, superstars. He’s come quite a way from the scratchy minimalism that marked the beats on Straight Outta Compton (the album, I mean).

Although the electronic-orchestral arrangements remain recognizably in Dre’s New Modern Style (as opposed to his High Keyboard Squiggle Style or his Old-School Turntable Style), Compton responds to Kendrick Lamar’s To Pimp a Butterfly the way 2001 responded to Eminem’s The Slim Shady LP. Just as 2001 emulated the gleeful humor, obscene verbal spew, and general brutality quotient of Dre’s most talented protégé at the time, so too does Compton aspire to the bitter anger, neurotic verbal spew, and cautious racial awareness of Dre’s most talented protégé right now. But where 2001 used a musical template Dre initially designed for Eminem, a style of minimal electronic loop whose childlike dinkiness suits Slim Shady’s impish ways far more than it does Dre’s blunt bluster, Compton doesn’t sound much like a Kendrick Lamar album — To Pimp a Butterfly made its most profound political statement by harnessing softer, richer beats than Dre’s usual to the workings of a live jazz ensemble, a coup Dre couldn’t possibly imitate without making himself look like a trendhopper. So Compton deploys patterned keyboards and screeching drum machines that sound very much like those on 2001, given a few tweaks here and there, beefed up with massive choruses and melodic interludes, all while Dre makes haughty pronouncements about the true state of hip-hop in Black America.

Unfortunately, in practice this often translates to haughty pronouncements about the true state of Dr. Dre in hip-hop — obsessing over his own rags-to-riches story, bellowing that he’s still a great artist and he’ll fuck up anybody who disagrees, he just can’t stop rubbing his celebrity in your face, and the album’s supposedly political lyrics say much less about the crime-infested city for which it was named than do the supposedly personal/specific/observational lyrics N.W.A. excelled at. Verbal message in itself has never been his specialty, after all. The album’s strength, as befits the farewell statement from rap’s paradigmatic musical tinkerer, is formal. Those augmented keyboard loops, at first sounding way too grand and way too cluttered simultaneously, prove tough and chewy as their sung refrains rush into sharp focus, and the whole thing builds from seething opener “Talk About It” to pompous victory lap “Talking to My Diary” with cool authority and symphonic grandeur, moving insistently from sampled soulgroove to raw bass crunch to cheesy Hollywood violin. While nothing here meets the measure of, say, 2001’s “Still D.R.E.,” whose brilliant spooky-tinkly synthesizer you can still hear glittering on modern hip-hop radio, Compton nevertheless proves a gripping, tough-minded listen. And despite too many self-absorbed odes to Dre’s own legacy, the album’s sharp electronic edges do, in the end, present and evoke a bleak, poverty-induced fatalism endemic to the African-American ghetto much the way Straight Outta Compton does (the movie, I mean).

Like the movie, Compton functions as a publicity device; both are components in a larger advertising campaign intended to spark an N.W.A. revival. Their ultimate significance, I suspect, will be to bring N.W.A. back into the public eye. Even if Dre goes back on his promise to retire from the music industry, a reunion seems unlikely — Eazy-E famously died of AIDS in 1995, and a year later DJ Yella quit the business to become a successful and prolific director of adult films. But N.W.A.’s old music remains so relevant today — after the murders of Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, Eric Garner, Tamir Rice, the list goes on — that in reviving songs like “Fuck tha Police,” Compton and the movie contribute both to the Black Lives Matter movement and a growing sense of racial consciousness among young consumers of popular music. If Compton and Straight Outta Compton (the movie) inspire a new generation of hip-hop fans to check out Ice Cube’s Amerikkka’s Most Wanted and Death Certificate, MC Ren’s Kizz My Black Azz and Eazy-E’s Eazy-Duz-It, Dre’s own solo debut The Chronic and of course Straight Outta Compton (the album), that will itself constitute a worthy achievement.

Since N.W.A. remain obscured by mythic misconceptions that could make the shrewdest advertising honcho gasp, my hopes for Straight Outta Compton (the movie) were low. It was going to distort their artistic substance no matter what; the only question was how. Whether it presented the group as cold-eyed realists telling objective, nonjudgmental but unsympathetic stories about what the ghetto is Really Like, whether it flatly denied the group’s many incitations to violence and framed them as underclass heroes, whether it endorsed such incitations and wrapped the whole project in an ethos of angry macho defiance (God help us), it couldn’t possibly capture the multiple layers of irony and roleplay that exempted them from the unexamined hate moral arbiters accuse them of circulating. Or so I thought — I wound up seriously enjoying the movie. Complain all you want that it a) gives MC Ren and DJ Yella very little screentime, b) villainizes Death Row executive and thug ringleader Suge Knight (who probably deserves it), c) sentimentalizes Eazy-E’s death (even though Jason Mitchell, the actor who played Eazy, delivered my favorite performance in the whole movie; even though the scenes directly beforehand where he gradually gets sicker and sicker are absolutely heartbreaking), d) omits Dre’s history of domestic violence, e) etc. It’s hardly an accident that the movie’s most sympathetic character is also the billionaire entrepreneur who financed and produced it, the same billionaire entrepreneur who recently signed a deal with Apple and whose new album just came out. Nevertheless, the film wasn’t meant to provide a totally realistic, true-to-life depiction of the group’s past, and even if it did, how would anyone in the audience know for sure? The film was meant to tell a legendary origin story, to find a position for N.W.A. in today’s culture, and in that it succeeds.

During the most terrifying scene in the film, the group has just finished recording a song in the studio, and they all step outside for a moment. Cops drive past, see five young black men standing idly around, pull over, pull out their guns, and force them all onto the ground. (Afterwards, once white manager Jerry Heller has convinced the cops to leave, Ice Cube writes “Fuck tha Police.”) It’s not the only such scene in the movie — early on, Cube walks past a crime scene and almost gets arrested himself; Dre finds himself in the wrong parking lot at the wrong time and does get arrested — and especially before the group officially bands together, the movie takes care to paint a brutally depressing setting, a backdrop whose reality the group would address in their music. So it’s a relief that the film didn’t then overstate or even particularly emphasize the group’s alleged/projected reality factor, always the key to understanding, or misunderstanding, N.W.A. Without belaboring the point, without pedantically spelling out the essence of N.W.A.’s art as its didactic soapbox allowed, the film makes clear that these rappers were playing personae onstage very different from their real-life selves. These real-life selves were, likewise, very different from those real-life selves portrayed in the movie, by definition. But by including so much music, so many scenes where Cube and Ren and Eazy rap whole verses uninterrupted, not to mention concert scenes where the group plays whole songs (including one where they play “Fuck tha Police” after being explicitly told not to, get arrested as a result, and hence win the publicity jackpot), the movie cannily and neatly bifurcates its characters. Each is a real person, and each has an assumed onstage persona. While this may seem elementary to anybody who doesn’t associate music with Pure Straight Honest Self-Representation, it’s a crucial insight regarding N.W.A., whose coded claims of authenticity prove tricky indeed.

“My identity by itself causes violence,” goes the key line on Straight Outta Compton (the album), delivered by a smug, sneering Eazy-E on the single most jaw-dropping verse of his career. According to official myth, N.W.A.’s crucial contribution to hip-hop was a measure of social realism previously unknown to the genre. They acted bloodthirsty and misogynistic because that’s how the ghetto is; you might not like it but it’s the ugly truth, we’re just representing our society here, we’re just telling real stories that happened to us. But with the possible exception of “8 Ball,” in which Eazy laconically drifts from crime scene to crime scene, they altogether lack the documentary framework, narrative detail, and objective tone typical of realist artists; they take too much pleasure in the brutality. Their true achievement is more wicked, and more brilliant: these were the first rappers ever to consciously reclaim demeaning stereotypes about black people and inhabit them with bitter irony, only the word “irony” makes the project sound affected rather than fierce, seething, raw. This rhetorical ploy would grow in stature over the following decade, but in 1988 it was wildly inventive and insane. If you fuckers really think of us like this, they seem to say, if you really think we’re vicious animals, fine then, that’s what we’ll be. If you think we’re angry monsters, well, that makes us really fucking angry. We’ll murder each other, sure, we’ll smack up our bitches, we’ll steal cars and kill cops and rhyme “warpath” with “bloodbath,” if that’s what you really think we’re like. Thus did they harness the violent rage falsely attributed to them (well, a representation of such) and redirect it at those doing the attributing, all while (another ironic twist) perversely enjoying that brand of rage now that they’ve got the chance. The homicidal villains they played onstage weren’t just characters to inhabit, they were deliberately exaggerated jokes about racial conflict and fear. Cube’s brawny whine and Eazy’s impossibly pinched, nasal drawlscreech, an instantly arresting sound no less irresistible for the superhuman reserves of cold, unfeeling contempt hidden beneath his delight in pronouncing rhythmic syllables, were the perfect voices for such a stance. Dre’s beats added crunch, muscle, wit, glee.

The first six songs on Straight Outta Compton (the album) are so musically original that only a censorship board could resent humming them — they’re so catchy without being cheerful, so harsh without being abrasive, so minimalist without being austere. Dre lays deep basslines under punchy drum machines and a particularly clipped, staccato, chicken-scratch style of guitar figure that fits so directly into the framework it barely sounds like a guitar at all, with Yella adding turntable dressing and ominous samples. Turning police sirens into music by way of the whiny riff on “Fuck tha Police” and the ostinato horn on “Straight Outta Compton,” chewing on a classic Isley Brothers hook until it turns sinister on “Parental Discretion Iz Advised,” setting offbeat rhythm chords dancing atop the bassline on “If It Ain’t Ruff” (while sampling a previous song on which Ren pronounces “He’s a gangsta in black and he’s about to attack” — only speeding the whole thing up and cutting one word, so it sounds more like “the gangsta’s black and he’s about to attack”), the blunt, stark sound Dre designs on these first six songs blasts from the speakers thrilled with its own power. The album’s second half isn’t awful, exactly, just fairly empty, home to a bunch of unembellished drumbeats, lame freestyles, conventional boasts that hardly fit the gangsta concept, and “Express Yourself,” the anomalously tame radio hit. You can salvage “Dopeman,” a ruthless ode to drug dealing; skip “I Ain’t tha 1,” in which Cube explains his philosophy of dating. So if Straight Outta Compton (the album) doesn’t cohere front to back, if it’s not the flawless masterpiece hip-hop obsessives believe, who cares? It still changed the genre forever. Whenever I’m in the mood for its tough, old-school groove and scabrous verbal abuse, I play the first six songs plus selected singles and B-sides that didn’t make the album: Eazy’s glorious “Boyz-n-the-Hood,” the original “Dopeman” (not the remixed version on Straight Outta Compton), and “A Bitch Iz A Bitch” (so much nastier and more entertaining than “I Ain’t tha 1”).

As the movie portrays so theatrically, N.W.A. didn’t last long. Cube left after their very first tour because he suspected (correctly, it turns out) manager Jerry Heller was screwing them with contract legalese, and after the other four released a second album called Niggaz4life in 1991, Dre’s departure for the Death Row label sealed the group’s demise. Feuding viciously with each other all the while, they all recorded worthy music after the split, with the exceptions of future pornography kingpin Yella and, tragically, Eazy, whose records got duller and duller as he, if we’re to trust the movie, found himself seduced irreversibly by wealth and all its benefits: a giant mansion, tons of drugs, an endless supply of women, and, eventually, HIV. But after leaving the group Cube soon embarked on a long, fruitful solo career, and while Ren wasn’t quite as prolific, I’m partial to his 1992 Kizz My Black Azz EP, home to raps even more cartoonish and sensationalistic than the ones he spat with N.W.A., plus beats whose kitschy strings and seedy funk samples evoke the blaxploitation movies N.W.A.’s own music didn’t. And Dre’s subsequent career proved a categorical success. Had he chosen to remain a producer exclusively rather than trying his hand as a rapper, too, he likely would have made quite a respectable name for himself; to this day he still produces several songs a year for select rappers deemed worthy of his august presence, and he has impressive credentials as a talent scout (Eminem, Kendrick Lamar). But it was The Chronic, his 1992 solo debut, that cemented his name as the archetypal producer-auteur.

No matter how strong the beats were on Straight Outta Compton (the album), The Chronic is the reason Dre gets respect as a musician. From beginning to end, each song locks perfectly into place, forming a flawless whole so flush with groove it’s almost airtight. Relaxed, coolheaded, supremely confident, building a style simultaneously slick and harsh from piercingly high keyboard squigglehooks, buzzing bass, and lounged-up flute, the sound Dre invented on The Chronic equalled a whole musical world, an immersive electronic environment no less hard-hitting than his work with N.W.A. for its slower tempos and stickier textures. Packing the album with samples (especially from Parliament-Funkadelic; “The Roach” is basically the same song as “P-Funk Wants to Get Funked Up”), Dre was proud to acknowledge roots in ‘70s funk as well as the bleaker, more theatrical music artists like Curtis Mayfield and Isaac Hayes were recording for blaxploitation movies, but he warps said sources into something colder, harsher, more alienated; with Bernie Worrell’s shiny keyboards sharpened and raised several octaves, and Donny Hathaway’s flutes polished and squeezed into the mix, he filters and distorts said funk through a scary, dehumanizing technological lens, and the resulting music gleams with stark power. Honey-tongued partner in crime Snoop Doggy Dogg appears almost as often as Dre himself, skipping in circles around the somewhat cruder, clumsier boss with mischievous glee. In a musical context, their boasting, as violent as that of N.W.A. but altogether lacking the ironic exaggeration that transformed stereotype reclamation into genuine racial/political protest, takes on disturbing Staggerlee resonances, which is why The Chronic recalls blaxploitation far more than Straight Outta Compton (the album). This is real glamorous outlaw material, deliberately playing into an extreme but also common fantasy of the undefeated renegade black male fucking and murdering his way through a hostile world. Perhaps all gangsta rappers do this; certainly they all brag about sex and murder. But Dre fashioned such an irresistible musical frame, not to mention such a historically conscious one, that his outlaw posturing turned eerie, compelling, impossible to shake. To this day few other hip-hop records expound the Staggerlee fantasy so seductively. I recommend playing it in your car and letting your jaw drop, amazed, at how completely the squealing keyboards fill the space while slicing through the air.

After releasing The Chronic, Dre went on hiatus for seven years, working only as a producer as he lay back and watched how utterly his music would transform the hip-hop landscape. In 1999 he released 2001, keyed to a somewhat overblown comeback narrative that nevertheless produced several thrilling songs. By then his style had changed; his high, glossy hooks had fallen out of fashion, replaced by simpler, more aggressive synthesizer loops. And then he went on hiatus again until releasing Compton this year. The Dr. Dre of 2015 is a very different person from the Dr. Dre of 1992: no longer a gifted musician trying to capture his visions on record, he’s now succeeded on such a scale that the urban legend stating he wears a new pair of Nike sneakers every single day, although silly, isn’t altogether impossible. Rather than pretending he’s still a gangsta, Compton addresses his success directly.

Sturdy, swaggering, imbued with a sense of grandiose mastery symptomatic of an ego swollen well beyond an ordinary human being’s comprehension, Compton’s superb command does Dre’s inflated reputation proud even as it raises eyebrows about his agency. It’s a big, long record packed with collaborators, and Dre shares more production credits with various rival craftsmen than his standing as a consummate beatmaker might allow: since he’s never claimed to be himself a great rapper, or a great lyricist, or a great vocalist, what could he have contributed if the music’s not entirely his? Writers like King Mez get credit for the words, Dem Jointz and Cardiak get credit for the beats, all so Dre can slap his pricey brand name on the final product? And this from an artist who hasn’t released an album in sixteen years due to “perfectionism”? Well, yes, actually, silly as it may sound, Dre is famous for using collaborators like instruments in a larger piece. Allegedly, he keeps musicians in the studio for days, forcing them to improvise and refine beats and hooks until they’ve played exactly what he wanted, and he retains ultimate control over his writers in much the same way. As a frontman, he’s a construction (much like Eazy-E, who never rapped his own verses and whose persona was invented by Ice Cube and MC Ren as the Ideal Fictional Rapper); in the studio, he’s the boss. Whether or not he actually wrote this bassline or that keyboard flicker, it all sounds like him. The caustic drumslams on “Genocide,” sour femme chorus on “Satisfiction,” sore electric harpsichord on “All in a Day’s Work,” and rough rhythm guitar underpinning “One Shot One Kill” share an aggressive and/or symphonic tone with 2001 and much of his subsequent production work for other rappers. Despite way more guest verses than even 2001 offered — from dozens of anonymous hirelings, from Snoop, from Eminem, from Kendrick Lamar, whose agitated chatter jolts the music to life much the way Eminem’s pottymouth livened up 2001 — there’s no doubt who’s responsible for the overarching structure and the general musical signature on this totally cohesive, through-composed auteur’s record. Anyway, the ensemble cast album is itself a venerable hip-hop tradition, and Compton’s endless cavalcade of new voices freshens beats whose electronic luxury might otherwise run dry were Dre the only presence at the mic.

A fifty-year-old man looking back on a fruitful if sparse career, Dre couldn’t possibly imitate his past triumphs — both Straight Outta Compton’s over-the-top shock humor and The Chronic’s romanticization of the black outlaw would look exceedingly willful and stupid coming from a wealthy businessman twenty years later, and anyway, one reason his reputation remains so pristine is because he never repeats himself. Compton attempts to stay relevant with honest political commentary, describing police brutality and gang violence in a tone that’s pained, bitter, forthright. But although magazines from Rolling Stone to USA Today have emphasized the album’s moments of protest, they’re not prevalent; Compton merely includes them in a more traditional framework of typical rap braggadocio, which in Dre’s case mainly concerns his legacy. On his last official album, his final stand in the public eye, his foremost desire is to make sure everybody remembers how great he is. So he plays up the nostalgia factor and reminisces about the good old days when N.W.A. was still together writing songs in the studio, reminding us countless times that he’s the man who invented motherfuckin’ gangsta rap, and generally flexing his ego. The album’s nowhere near as aurally charming and conceptually shrewd as The Chronic; its inferiority is assumed, rhetorically, by the very nature of its nostalgia. But anyone who can tolerate a modicum of bombast will savor these swanky synthesizer hooks, most of the guest rappers are fairly talented, and in the end Compton coheres as a sane, measured testament to celebrity, as makes sense for a final goodbye. Dre deserves such a testament if anyone does.

The standout track on Compton is called “Animals,” and it’s the most politically explicit. A shuddering slow burner of a song, its hissing, clinical bleep effects crawling nervously over slapped bass and an irregular drum machine as Dre raps in a meter faster and fierier than his norm, “Animals” addresses the riots in Ferguson, Baltimore, too many places. Neosoul singer Anderson Paak provides the chorus: “The white folks tell me all the looting and the shooting’s insane/but you don’t know our pain/please don’t come around these parts and tell me that we all a bunch of animals/the only time they wanna turn the cameras on is when we tearing shit up/come on.” Should Dre choose not to retire after Compton and one day grace his fans with another album, it would be a pleasure to hear him embrace this mode of protest, so much more direct than any of his past strategies. Should Compton prove his last, it will serve just fine as a strong, felt goodbye.

Compton (2015) is available from Amazon and other online retailers.