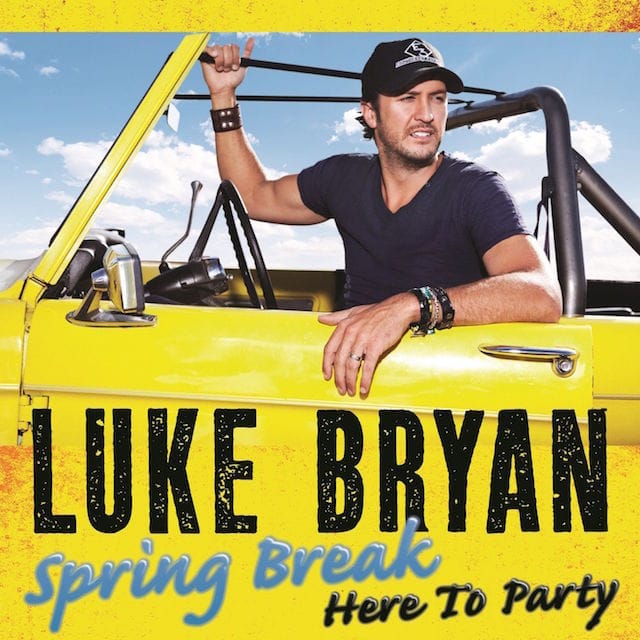

Luke Bryan Goes on Spring Break

Say what you will about Luke Bryan, but you have to admit the dude knows how to motherfuckin’ party.

Say what you will about Luke Bryan, but you have to admit the dude knows how to motherfuckin’ party. Come spring break and he’s out of town faster than a speeding bullet once he’s loaded up his truck with kegs and coolers. He doesn’t even bother checking into his hotel once he hits the coast, hell no, he heads straight for the beach. During the day he’ll swim, play volleyball with his buddies, and lie down on his towel soaking up the sun as surrounding young women admire his ripped, throbbing bod. In the evening he sets up his speakers in the back of the truck and has a tailgate party in the parking lot complete with rockin’ tunes, drinkin’ games, and as much casual sex as said ripped, throbbing bod can take. Yeah, bro! Spring break! Drink up before all the beer is gone! Let’s chest-thump! Whooooooooo!

Uncommonly prolific for such a big-time country star, Bryan has released a short spring break-themed EP every March for seven years: Spring Break With All My Friends in 2009, Spring Break 2… Hangover Edition in 2010, Spring Break 3… It’s A Shore Thing in 2011, Spring Break 4… Suntan City in 2012, Spring Break 6… Like We Ain’t Ever in 2014, and Spring Break… Checkin’ Out in 2015. There was no Spring Break 5, but in 2013 the first four records plus two new songs were released as the compilation Spring Break… Here to Party. The latter two records have also been compiled into a larger package, confusingly also titled Spring Break… Checkin’ Out. Lighter and friendlier than the mushy corn that dominates his official albums, the EPs consist of optimistic party anthems; their basic mood is celebratory. Supposedly, Checkin’ Out is the last entry in the series, but even if he keeps that promise, don’t expect his themes to change. Bryan’s special brand of beer-fueled, truck-driven hedonism has been far too successful, far too lucrative, for the good folks at Capitol to allow their brilliant corporate creation anything resembling artistic growth or a change of pace.

Although Bryan records in Nashville like every other country superstar, his fixation on spring break and the Florida coast (specifically, Panama City Beach, where he played an annual concert to celebrate the release of each EP) implies a general sense of distance from that town and its musical conventions, because he isn’t a country superstar, really. Devoid of not just the Calvinist stoicism that marks classic country but the commitment to downhome family values that defines and often ruins modern country, Bryan shares rather few sonic hallmarks with country of any stripe. Even in an era when Music Row has taken over vast portions of adult contemporary radio, his only consistent identifier as a country musician — besides the occasional banjo riff or strummed acoustic chord progression — is his fruity Southern accent. Complete with booming drums, slashing power chords, and guitar riffs whose swaggering macho crashes through the speakers like a truck edging you off the highway, this is straightforward stadium rock of the lowest common denominator, soaring through moments of inspirational fist-pumping bravado toward depressingly predictable anthemic climaxes. Although he’s proven himself capable of upbeat rockers and slinky pop vehicles, his métier is the inflated power ballad, always projecting the same persona whether he’s getting rowdy with his friends or misty-eyed over some inane memory from his childhood. The Luke Bryan character he plays on record was born in the rural South, became popular in high school, and attended some mediocre party college where he whiled the hours away drinking with his frat brothers and seducing a long line of sorority girls. Today, at 38, he attends all his school reunions and frat functions, remembers the good old days with pleasure, and gets unreasonably excited about spring break because it means he can once more engage in the youthful behavior he did all the time in college. Bryan can’t be like this in real life; for one, he’s married with children. But he sure puts a lot of effort into playing a definitely but not exclusively Southern male archetype, one that usually gets what he wants and ain’t working-class. Does that sound like country music to you?

More coherent musically and conceptually than Here to Party, the longer Checkin’ Out package unloads megariff after megariff in an expert and somewhat pleasurable melodic sequence. Despite the opener, an embarrassingly moony ode to his trusty old Ford Bronco (the same car O.J. Simpson used to flee from the police, by the way), halfway through the compilation he does score a few genuinely enjoyable songs, most notably “Checkin’ Out,” which combines bristly acoustic guitar and high electric piano for a hummable, blues-tinged confection, and “Good Lookin’ Girl,” an even catchier tribute to its title inamorata (though one must wonder whether he calls her good lookin’ girl because he just can’t remember her name). When he gets rocking hard enough, he has a way of plowing through your reservations and making you nod along in blissful, mindless acceptance. Then again, because this is supposed to be his last spring break-themed album and hence his big goodbye, he also emphasizes his nostalgic side, and thus piles on the feelgood confessionals, the reflective reminiscence, the haunted post-break recollections of golden days, the forlorn realizations that everything good must come to an end. While only “Spring Breakdown” uses the literary device that characterized 2013’s saccharine bestseller Crash My Party, namely the aged and experienced narrator looking back fondly on his youth, a shadow of hokey regret is cast across the whole record, considerably limiting its utility as party music. He buys his buddies one last round of shots; he despairingly wishes he had met that magic girl earlier during break; he knows his memories of her and the beach will follow him home. So then he gets everybody together to have the time of their lives for one epic, final night.

The nostalgia factor is crucial because it transforms what would otherwise be happy, lively rock & roll into something else entirely, with spring break changing from a mere party setting to an imagined symbolic utopia as vivid and irretrievable as James Taylor’s Carolina or Roy Orbison’s Blue Bayou. After all, Bryan doesn’t just want to have fun with his friends and get drunk and hook up; he wants to look back on and get sentimental about it. With only occasional exceptions (the kickass, swaggering “That’s My Kind of Night,” his one undeniably great work of art, or the rousing “Suntan City,” a decently hummable tune), retrospective sentimentality is the emotional foundation upon which the vast majority of his music stands. You can hear it in his grand, sweeping, reassuring melodies, in his hard, heavy, comforting backbeat, in the way his voice cracks when he delivers a big statement. You can hear it when he brings in a pedal steel guitar, say, adding wistful shades to an otherwise aggressive song, or when he plays a careful, tenderhearted acoustic arpeggio before launching into the next verse. You can hear it in the way his forceful, blaring anthems sledgehammer their choruses home. Thus do his paradigmatic themes of beer, girls, trucks and the like take on mythic proportions as he swears he would do anything just to relive those days. When I’m feeling generous, Bryan’s illusory vision of spring break strikes me as a viable escapist fantasy, projecting onto the Florida beach the happiness and release that, theoretically, is provided by the music. Then Bryan will launch into yet another overblown chorus, or juice up some word at the end of a line with a corny attempt at melisma, and I shudder.

Whether or not Checkin’ Out is actually his last entry in the series doesn’t matter; it fits the trope. That Bryan should then take his themes multiplatinum and achieve a wild success beyond the reach of even his most famous Nashville contemporaries is hardly a tribute to his musical universality or his pop vision. Rather, it says something fairly sad about his audience, and by extension about a big slice of the country. It says that people really do identify with the character Bryan plays on record, that many guys really have no life beyond macho posturing and reminiscing about the good old days. It says that Bryan’s pathetic spring break fantasy appeals to a whole demographic. It says that a significant chunk of white male America peaked in high school.

Spring Break… Checkin’ Out and Spring Break… Here to Party are available from Amazon and other online retailers.