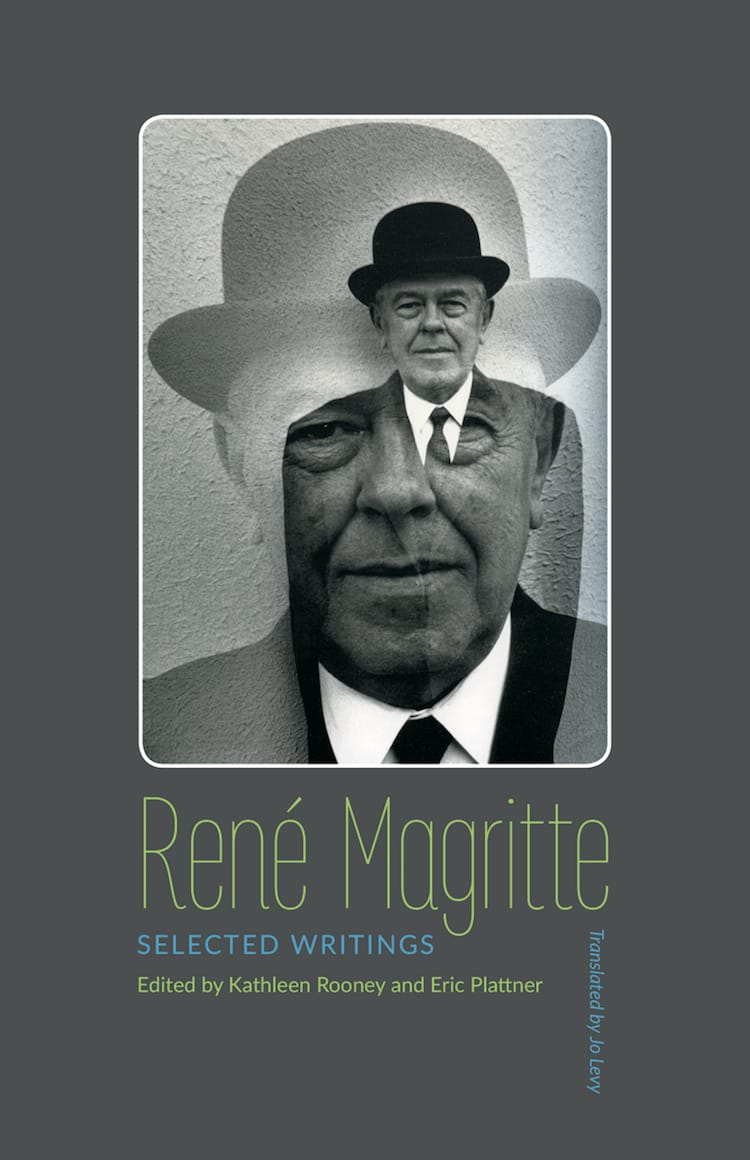

Magritte the Writer: An Interview with Kathleen Rooney

Kathleen Rooney's most recent project, René Magritte: Selected Writings, co-edited with Eric Plattner, is somewhat out of the ordinary for this Chicago-based writer. This book offers English speakers a chance to dive into the life of René Magritte, the lauded Belgian surrealist painter.

Kathleen Rooney is a founding editor of Rose Metal Press and the author of several books of poetry, nonfiction, and fiction, including the forthcoming novel, Lillian Boxfish Takes a Walk. However, Rooney’s most recent project, René Magritte: Selected Writings, co-edited with Eric Plattner, is somewhat out of the ordinary for this Chicago-based writer. This book offers English speakers a chance to dive into the life of René Magritte, the lauded Belgian surrealist painter. It includes more than a few personal letters and journals; the artist, unbeknownst to many of his fans, was a prolific writer, composing manifestos, prose poems, and even a few film scripts over the course of his lifetime. Rooney’s book provides an intimate glimpse into the artist’s mind while establishing his talent as a writer.

I spoke with Rooney via email about this project’s unexpected genesis, her relationship with Magritte, and the inquisitive, genre-bending nature of the artist’s writing.

* * *

Cassandra Balzer: Your bibliography is impressively expansive; you’ve experienced everything from novel-writing to a crazed jaunt into the world of literary remixes. What specifically was your role in the forthcoming project, and how does it compare to your previous work? What catalyzed your interest in assuming the role of editor rather than taking a more creative approach?

Kathleen Rooney: Thanks! I think that the key to my expansive bibliography in general and this project in particular is that one of my favorite emotions is curiosity — I’m super-curious about a lot of things, and I love a good mystery.

The origins of this project go back about two years, to late July of 2014 when I sort of accidentally stumbled on this long-lost manuscript. To be honest, it’s still kind of nuts to me that I — who have no academic background in art history (though I did work for years as a figure model) — have ended up helping to bring this book into the world. That summer, my friend and DePaul University colleague Eric Plattner and I went to the Mystery of the Ordinary, 1926-1938 show of Magritte’s work hosted by the Art Institute [of Chicago]. I’ve loved Magritte’s work ever since I was a kid, and I thought the show — which only came to the AIC, MoMA, and the Menil Collection in Houston — was excellent. As Eric and I went through, I was struck by the outstanding quality of the wall texts accompanying the paintings. Partway through the exhibit, it occurred to me that the texts were so well-done because they were excerpts of Magritte’s own writing.

As they funneled us out through the gift shop, I planned to buy a copy of his book. To my dismay, it wasn’t there. Through a lot of online and international detective work, I discovered that an English translation of Magritte’s writings had been commissioned and scheduled for publication in 1987 through John Calder’s Riverrun Press, but the publisher folded and the project never saw the light of day. So weirdly, a fully translated (albeit rough and typewritten) manuscript of Magritte’s Selected Writings by the now-dead translator Jo Levy had been languishing in an archive in Caen, France for close to 30 years, unbeknownst to just about anyone. Owing to the help of the librarian there, Alma Books (which held the rights to Riverrun’s catalogue) in the UK, and University of Minnesota Press here in the States, not to mention my phenomenal co-editor Eric, that manuscript is now a book, available to Magritte fans in English for the first time.

As for a more creative approach, the two-ish years that I ended up spending working with Eric to prepare this manuscript for publication did inspire me to take a creative angle on the material as well. I got to know Magritte and his household so deeply as I was reading his writing and working on my introduction, and that inspired me to write a novel-in-flash-fictions / prose poems told partly from the perspective of his wife, Georgette, and partly from the perspective of their series of beloved Pomeranian dogs, all called Loulou. It’s called The Listening Room.

CB: Why Magritte? As previously mentioned, his writing has never been published in English. What can fans of the artist expect from this publication?

KR: Magritte because, like I said, I’m a big fan and he’s the Belgian surrealist whose work I serendipitously happened upon (thanks to Eric’s Art Institute membership). It was like finding a Picasso at a yard sale or something, like “Can no one else have gotten to this before now?”

Fans can expect a witty, opinionated, and mysterious look into the mind of one of the most influential artists of the 20th century. I say in my intro that Magritte is essentially a writer’s painter, so it probably isn’t surprising that his written output is so delightful. There are manifestos, prose poems, flash fictions, detective stories, interviews, reviews, polemics and all kinds of hard-to-classify texts (even film scripts!) in here, and it’s the kind of book that is rewarding to read both straight through and in small leaps in and out.

CB: Aside from the artist in question, what about this project drew you in?

KR: Aside from not having a background in art history, I do know good writing when I see it, and I found it incredibly galling that this stuff was not more widely available in English. Magritte is a great painter — that is well understood. But the more I read the writing itself, the more I realized what a wonderful writer he is as well. Reading the book, of course, gives you a great deal of insight into his work and creative process, but even people who are not fans of Magritte will find a lot to admire here just in terms of literary quality. Both Alma and University of Minnesota initially discussed with us whether we thought illustrations or images were needed, and we concluded that they were not because this work is so capable of standing totally on its own.

CB: I think that’s an interesting and important decision. In choosing to not include his visual artwork, you’re almost forcing the reader to acknowledge his prowess as a writer.

KR: Exactly. Or if not to force, then at least to encourage them to seriously consider his prowess as a writer. It also gives the reader a choose-your-own-adventure option in terms of how they want to engage with the book. They could choose to read it as-is, totally sans images, and have a rewarding experience that way. Or they could open up their browser to Google “image search” and choose to look up images as needed every time a painting gets mentioned, or simply when they’re curious about a particular image. This latter approach can be especially fun with the pieces that do refer heavily to his visual output, like one of my favorites, “On Titles,” a long list piece, which begins:

1. General comments apropos of titles:

The titles of pictures are not explanations and pictures are not illustrations of titles. The relationship between title and picture is poetic, that is, it only catches some of the object’s characteristics of which we are usually unconscious, but which we sometimes intuit, when extraordinary events take place which logic has not yet managed to elucidate.

We imagine the tree to be living in wonderland. To this end, the landscape and the tree have human features.

The amazing discovery of fire. Thanks to the friction of two bodies together, suggestive of the physical mechanism of pleasure.

Here, the idea of playing truant is applied to objects.

Life is no longer represented on a stage set, the roving imagination sees life as a show.

In the forest a hunter meets an art show.

The cat still exists in the twentieth century. The legend bursts into modern life.

CB: If the work had been more widely distributed, do you think Magritte’s writing would have held its own at the time? Was there ever a possibility of René Magritte becoming a figure – major or minor – in Belgian literature?

KR: Actually, when he was younger, Magritte did seem to want to be a writer more than a painter, and even drafted some detective novels, as part of his juvenilia, under the pseudonym “Renghis,” which he arrived at by portmanteau-ing his first name, René, and his middle name, “Ghislain.” There’s also an interview in this book in which the interviewer, André Gomez, asks Magritte how he got into painting and how he decided to give up writing and poetry in order to paint. Magritte insists that he never really gave anything up, and says at one point: “Ah, well, don’t you see that I had no choice, no more than I could choose the color of my hair. It happened. I don’t know how it happened. I have always painted. I really don’t remember how it came about.” [the exchange can be read here]

Throughout the book, it’s fascinating to see Magritte doing what today we might call “literary citizenship,” contributing both writings and images to the little magazines of his day, including those run by his fellow Surrealists, such as 391 and Période in the 1920s, as well as his friend, the poet Paul Colinet’s zine (avant la lettre) Vendredi in the 1950s. Magritte even made his own idiosyncratic, zine-like publication, La Carte d’après Nature, in the 1950s and ’60s. So his literary output continued for much of his life, alongside his artistic output — just on a much smaller and more independent scale than his paintings, which eventually hit that stratospheric art-star level.

CB: Is there a perceivable difference between Magritte the Painter and Magritte the Writer? You mentioned not having an art history background, but does his writing lend itself to a better understanding of his visual artwork? Does the artist’s particular brand of surrealism inform the writing?

KR: There are, as you’d expect, differences and similarities. Some of the pieces have nothing directly to do with Magritte the Painter aside from sharing a dreamy, witty, and Surrealist bent, whereas others concern similar subjects as his paintings. And in the manifestos, such as “Surrealism in the Sunshine,” he’s absolutely articulating for himself and for others his politics and aesthetics, both as a writer and as a painter. One of my favorite examples of this kind of expression is actually in [the essay] “Surrealism in the Sunshine,” and I quote it a lot when I’m talking about Magritte, I think because it’s such a smart and hopeful way of looking, not just at his writing and painting, but also at the world in general. He says:

Life is wasted when we make it more terrifying, precisely because it is so easy to do so. It is an easy task because people who are intellectually lazy are convinced that this miserable terror is “the truth,” that this terror is knowledge of the “extra-mental” world. This is an easy way out resulting in a banal explanation of the world as terrifying. Creating enchantment is an effective means of counteracting this depressing, banal habit.

Magritte creates enchantment all the time as a writer and as a painter, and the Selected Writings gives us new ways of seeing how he thought about and achieved that.

René Magritte: Selected Writings (2016) is published by University of Minnesota Press and is available from Amazon and other online booksellers.