Mapping a Feminist Cosmos

Without didacticism, Sandra Vásquez de la Horra makes visible the connection between the exploitation of the natural world and the subordination of women.

LOS ANGELES — Art, at its very best, reminds me that there is a world out there that I not only belong to but trust — perhaps even love. Sandra Vásquez de la Horra’s beeswax-dipped drawings of erupting women, mystical landscapes, and hallucinatory flora in The Awake Volcanoes at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, did just that. Oh, that old mystery of finding oneself reflected in the material fragments of someone else’s private imaginary. After all these years and an untold number of visits to galleries and museums, it astonishes me anew when the adage proves true: that by following the strangest, most idiosyncratic contours of vision, it’s possible to arrive at a general truth.

Yes: contained within the particular, the universal. Why else would I see in the taupe figure at the center of the opening work, “Volcánica (The Volcanic Woman)” (2023), composed of smoke and bubbles spewing from crimson volcanic nipples, precisely the same fury, wonder, verve, and appetite that animates my own animal body? Given that the artist was born in Chile, raised Catholic under Augusto Pinochet’s dictatorial regime, and later moved to Germany, where she studied art and began practicing Santería, it’s safe to say that this resonance has less to do with shared biography than something beneath the surface.

The entire show is full of this familiar strangeness. Flanking that first image are two accordion-folded paper sculptures of reclining women. In “Del sol naciente (From the Rising Sun)” (2023), an infant is cradled between the woman’s erect breasts; viewed from one side, her skin resembles wood grain — rooted but leaden, more instrument of the cycle of life than carnal body. From the other side, she is radiant, amber, and fuchsia: all heat and kinetic energy. The same dynamic appears in “Volver a ti (Coming Back to You)” (2023): vibrantly colored on one side, wooden on the other, except here the child at her chest is replaced by a man folded between her knees, his mouth at her navel. Show me a woman who hasn’t felt both objectified and embodied, burdened and revitalized by the demands of sex and child-rearing.

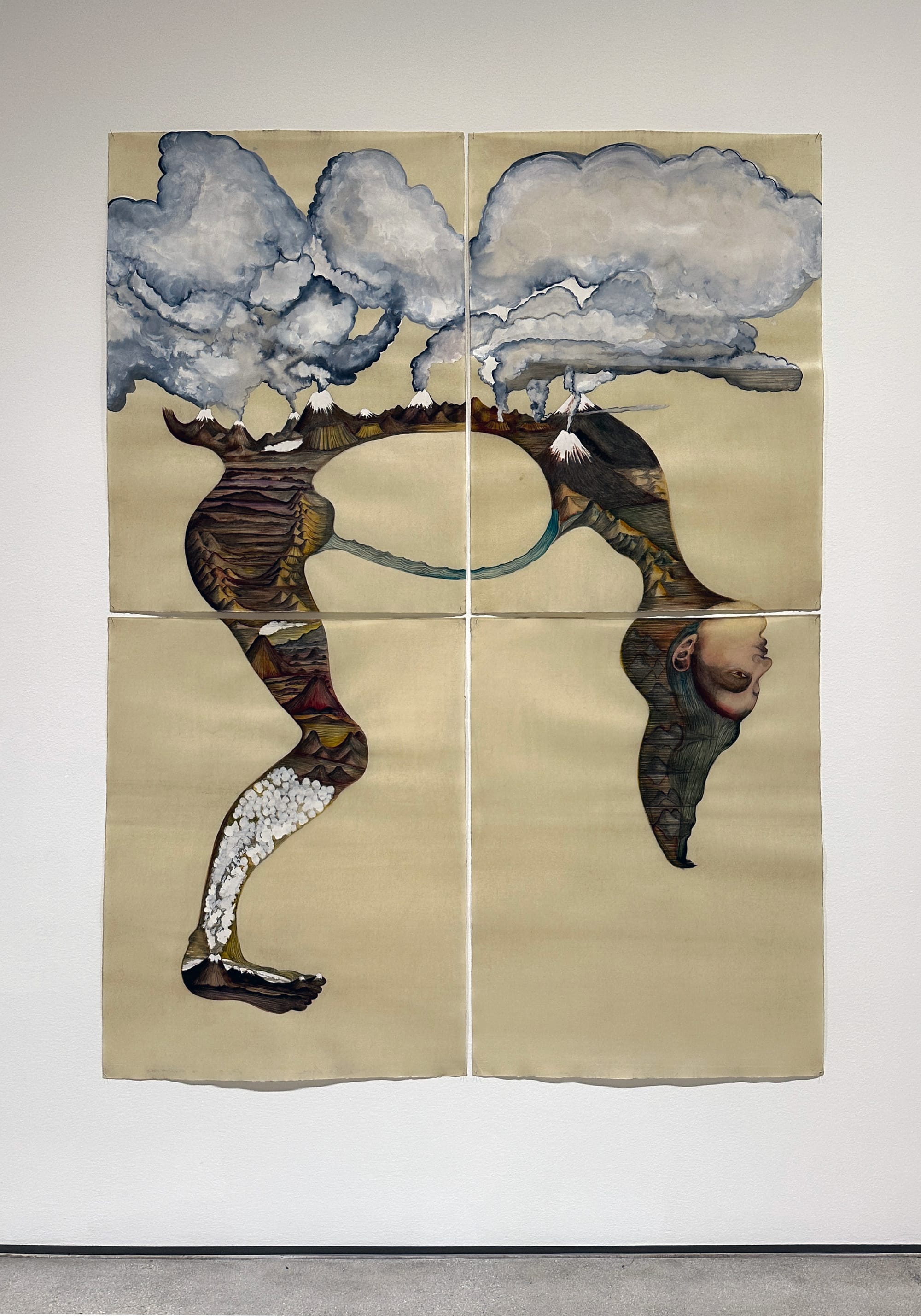

Across nearly 100 drawings, female figures meet, merge, and cleave from mountain ranges, wild animals, citrus trees, and sprouting fungi, as well as elemental forces like water, lava, rainbows, and celestial bodies. In “Anillo de fuego (Ring of Fire)” (2023), a female figure is arched into a backbend, snowcapped volcanoes chugging smoke lining her abdomen. She is not separate from the earth, but of it, undifferentiated and indivisible. Another unframed, large-scale drawing on buttery yellow paper, “Deidad planetaria (Planetary Deity)” (2015), depicts a woman with serpents wrapped around her head and a stag positioned before her crotch; she stands with one foot on the globe, a wooden staff in her hand. In the clustered botanical works, ovaries, stamens, and pistils frame the reproductive machinery of plants and humans as variations on the same ecstatic impulse.

Vásquez de la Horra’s recycled motifs don’t congeal into symbols so much as demonstrate how everything is connected, how every particle and atom is used over and over again, how this is true and miraculous and too easily forgotten. Hers is an ecofeminism rooted in the porous, reciprocal entanglements of the body and the world that made it.

Yet for all the mythic exuberance, these drawings never drift far from the ground of lived experience and the forces shaping it. The massive salon-style layout along the back wall brims with images incorporating texts — rallying cries such as “el pueblo unido jamás será vencido” (the people united will never be defeated) and “la voz de un pueblo que lucha” (the voice of a nation that struggles) — suggesting that collective resistance is often carried out both by and upon women’s bodies. Without didacticism, she makes visible the connection between the exploitation of the natural world and the subordination of women. In her cosmology, to liberate one body — be it biological, ecological, or political — is to liberate them all. Our struggles are not all that different after all.

Sandra Vásquez de la Horra: The Awake Volcanoes continues at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles (1717 East 7th Street, Downtown, Los Angeles), through March 1, 2026. The exhibition was organized by the Denver Art Museum and curated by Raphael Fonseca. The presentation at ICA LA was curated by Amanda Sroka with Emilia Shaffer-Del Valle and Amelie Wu.