Marigold Santos Takes Root

She uses epiphytes — plants that grow on other plants without harming them — as a framework for the expansive ways diasporas form.

TORONTO — The only thing most people know about epiphytes, if they know about them at all, is that they’re rootless. That’s not quite true — they develop highly specialized root systems adapted to wherever they land. In Epiphytic Elucidations at Patel Brown Gallery, Calgary-based artist Marigold Santos takes this fact as more than a metaphor. The exhibition uses epiphytes — plants that grow on other plants without harming them — as a framework for the expansive ways diasporas form through material labor.

To this end, she considers both her own labor and the histories of the material she uses. The exhibition's sharpest work, “shroud epiphyte (bilibid chair)” (all works 2025), references a 1914 photograph of an incarcerated Filipina mother seated in a rattan peacock chair at Bilibid Prison in Manila. The chair — produced by imprisoned artisans under American colonial rule and later sold to tourists and exported worldwide — became a global design icon whose origins were laundered through extensive commodification. Santos paints the seated figure as an epiphyte clinging to the chair as host, but the relationship is less than symbiotic: The peacock chair was circulated through parasitism disguised as benevolence, the exact logic of American colonial rule in the Philippines.

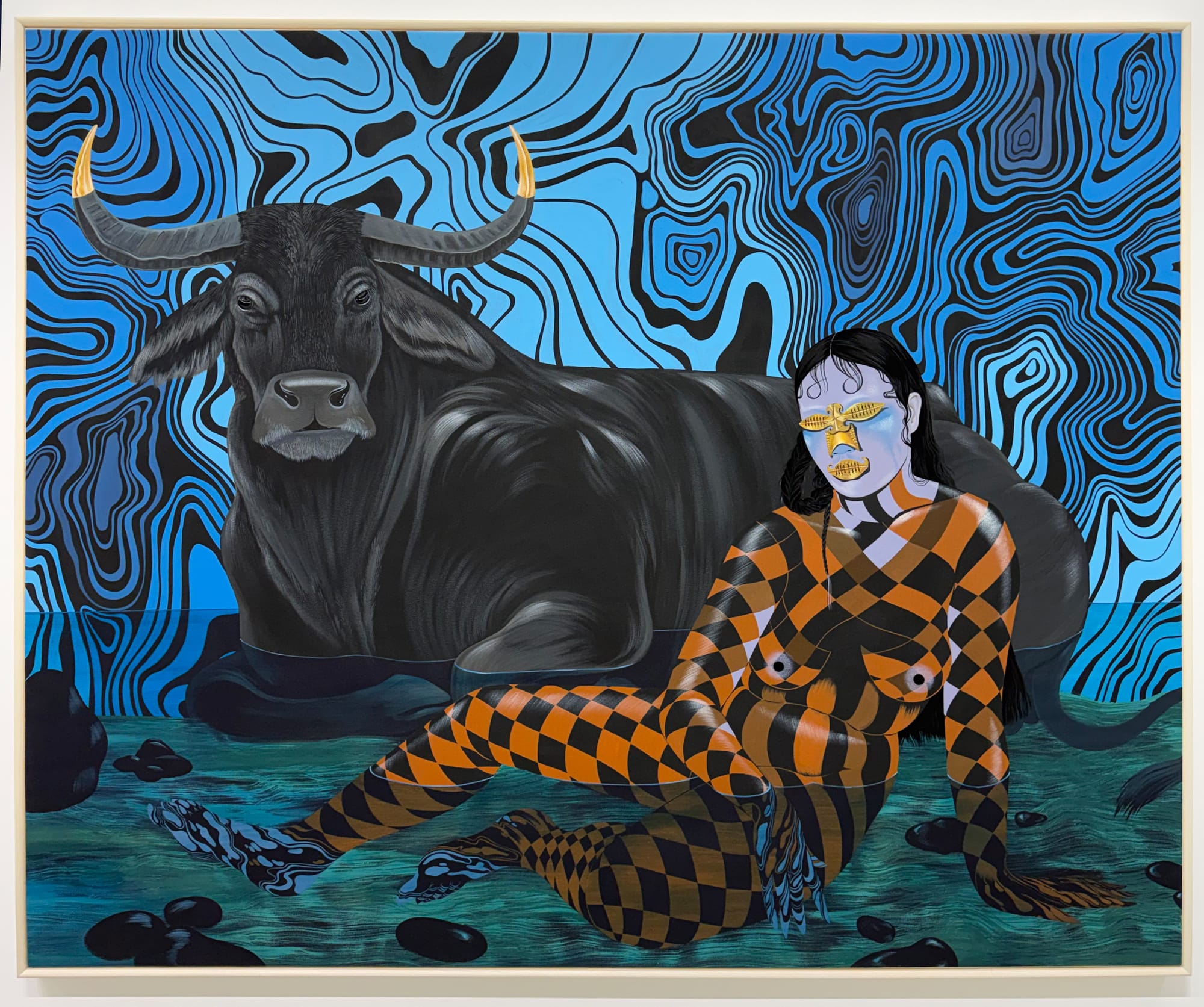

That insistence on embedded labor runs through the exhibition. In “nacre,” Santos assembles capiz shells — each hand-cleaned and acid-treated to become malleable — into an amorphous creature resembling an aswang, the shape-shifting figure of Philippine folklore, studded with bloodshot brass eyes. Material has to be broken down before it can take form, she suggests, a process that mirrors the work of remaking yourself elsewhere. “shroud (kalabaw and death mask),” meanwhile, pairs a water buffalo with a gold-masked figure, their forms mirroring each other in quiet mutual dependence — the kalabaw embodying generations of agricultural labor, the gold death mask recalling both precolonial artistry and colonial plunder. The gold is both inheritance and evidence of theft; Santos insists on holding both at once, refusing to let one negate the other. Resistance against imperialism and erasure manifests through this double-edged tension, through labor and cultural perseverance.

Santos' paintings are lush, vibrant, and otherworldly, but their real power is structural. As curators Chloe Panaligan and Marissa Largo note in the accompanying text, Santos's practice mirrors the diasporic experience — fragmenting and reconstituting identity through cultural transmission. Every material choice here carries the weight of someone's hands — imprisoned weavers, shell harvesters, Santos herself. The work insists that diaspora isn't defined by what's been lost, but by the labor of those who continually make survival possible.

Marigold Santos: Epiphytic Elucidations continues at Patel Brown (21 Wade Avenue, Unit 2, Toronto, Canada) through February 28. The exhibition was organized by the gallery.