Notes Toward A "Just" Image

Noted photography blogger Joerg Colberg [http://jmcolberg.com/weblog/] has responded [http://jmcolberg.com/weblog/2011/07/what_is_the_real_question/] to my piece [http://hyperallergic.com/28555/capitalist-realism-or-poverty-porn/] on the work of Shelby Lee Adams. Colberg states that "it would help u

Noted photography blogger Joerg Colberg has responded to my piece on the work of Shelby Lee Adams. Colberg states that “it would help us a bit to realize that our hand-wringing about these photographs ultimately won’t have any consequences – unless we spring into some sort of actual action. Telling Shelby Lee Adams to lay off obviously isn’t going to help anyone but ourselves: It is us who can then feel better – no more photographs of poor people to look at. No more guilt, while the people depicted in his photographs continue to live in poverty. Is that what we want?”

Excluding the poor and marginalized from photography is not the answer. Colberg is correct when he writes of guilt absolution. There’s a strange irony when the middle and upper classes seek to shield the poor from the camera’s potential victimization by rendering them invisible. No picture can bridge class divides or rectify generations of systematic exploitation. These tasks are beyond the capacity of any single photographer. Colberg also questions the lack of critiques for photographs of wealthy people, referencing the work of Martin Parr, although Tina Barney with her directed portraits of wealthy Americans is probably a more apt example. He states that “for the debate abound Shelby Lee Adams to make sense, we have to be able to apply large parts of it to photographs of people who occupy the complete opposite spectrum of wealth…The fact that we’re seeing objections to photographs of poor people, while we’re happy to ogle at rich people, might just indicate that the real problem is not necessarily a photography one.” The problem is not entirely photographic. I agree that the rich are just as open to mythologizing. Socially charged sites, both rich and poor, attract careerist predators (take a look at the controversy surrounding Kirsha Kaechele) just as much as they facilitate work that is linked with consciousness raising and demand for reform. But let’s be real: gawking at a debutante ball is hardly comparable to the long history of rural Appalachian images being used to rationalize poverty.

My hesitation about Adams stems from the characterization of his work as purely documentary. Photography is haunted by a dualism that posits the viewer between science and subjectivity. I do not contend that there exists a single objective reality which is easily captured in a picture, nor do I believe that veracity in a photograph is dependent entirely on technique or the absence of direction—snapping away randomly isn’t likely to be any more truthful than a carefully framed, thought out shot—but the degree of input Adams has in styling his subjects seems disingenuous at times. Socioportraiture given some dramatic coaxing for effect. The political dimensions of aesthetic decisions and the sensationalized narratives they suggest should not be overlooked. I say this as an admirer of his work. I’m not just concerned with images that portend to be “truthful,” but with how those images are situated politically, how they function as commodities. Admittedly, some of that situating resides with the audience and is beyond the role of the photographer.

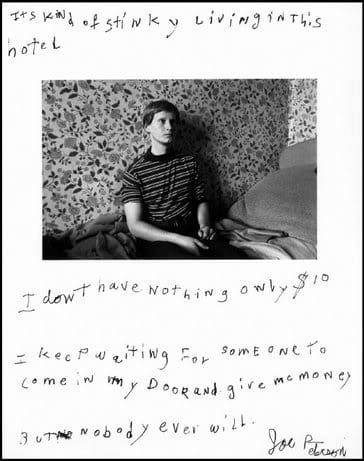

My “real question,” in response to Colberg, is whether documentary photographers working should work beyond pure aesthetic concerns and structure their practice so that it incorporates more radical analyses of social ills. If so, what would such a practice look like? The work of Jim Goldberg comes to mind, especially his Rich and Poor. Goldberg pushes the boundaries of “straight” documentary by incorporating text and anecdotes written by his subjects into his image-making. Is it possible to produce a Barthesian “just” image, “an image which would be both justice and accuracy,” without inhibiting aesthetic freedom?