Picturing Russia's Central Asian Diaspora

Travel to Russia these days, and chances are the person serving you your food is a visitor to the country, too. Every year, 5-6 million Uzbek, Tadjik and Kyrgyz people arrive in the country to work in restaurants, construction sites, farms and manufacturing plants. They are maids, taxi drivers, stre

Travel to Russia these days, and chances are the person serving you your food is a visitor to the country, too. Every year, 5-6 million Uzbek, Tadjik and Kyrgyz people arrive in the country to work in restaurants, construction sites, farms and manufacturing plants. They are maids, taxi drivers, street sweepers and garbage collectors. In Krgystzstan alone, one quarter of working-age citizens live outside the country.

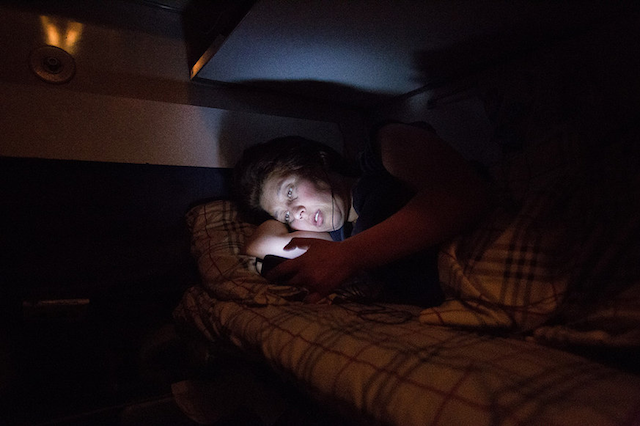

“Fewer and fewer people [in Central Asia] have never been to Russia,” documentary photographer Elyor Nematov told Hyperallergic. Nematov was born in Uzbekistan, and he counts his father and brother among the migrants. It’s what inspired him to document the train journey from Bishkek that many take into Russia, the challenges they face once they arrive, and what happens to their loved ones back home. Nematov’s I AM A FOREIGNER, soon to be on display at New York’s Photoville, illuminates an important chapter in the history of the region.

“Each migrant worker has his own experience, but many are second-class people in Russia. Prejudice against migrants is the basis for an understanding of migrants,” Nematov said, alluding to the fact that Central Asians often migrate illegally and, for that reason, are more easily exploited. They live and work in often-times poor conditions, sometimes receiving only one-third of their promised salary wage, and sending the little pay they get back home to their families. Fewer than 10% have health insurance.

Despite such problems, interdependence between Central Asia and Russia has not only increased, but it has also embedded itself in social life, as Nematov’s photographs make clear. “For some Central Asian families, it’s important for people to be in Russia, to survive there and earn money,” Nematov explained. “Now when you get married, the parents of your bride may ask you, ‘Have you been to Russia?’”

* * *