The Lavish Work of One of the Last Gilders of the Versailles Court

The first exhibition on 18th-century bronze chaser and gilder Pierre Gouthière at the Frick Collection brings together lavish examples of his work for the French court of Versailles.

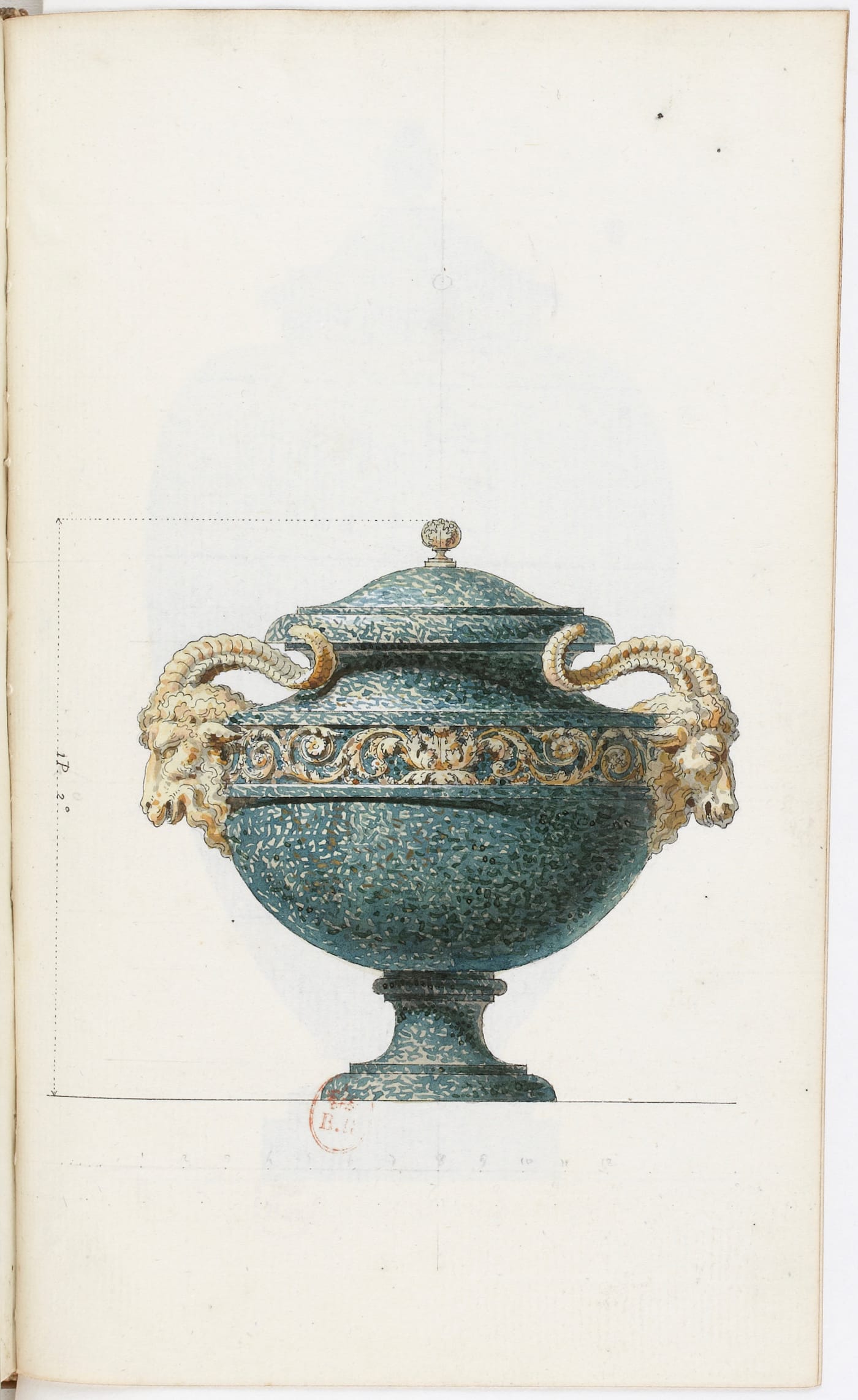

The details on the 18th-century gilt bronze work of Pierre Gouthière are lush with naturalistic texture, whether the flowing fur of a ram’s head, or the supple skin of a satyress. The French bronze chaser and gilder worked for the very elite of royal society, first under Louis XV, then Louis XVI. And while many of his decadent clients lost their heads (including Marie Antoinette and the Countess Du Barry), or had to flee angry mobs (like the Count of Artois who became King Charles X), Gouthière didn’t die in the French Revolution, but impoverished in 1813, because he wasn’t as good of a businessman as he was an artist.

Pierre Gouthière: Virtuoso Gilder at the French Court at the Frick Collection in Manhattan is the first exhibition to concentrate on his career, with over 20 glistening objects on loan from private collections and institutions like the Louvre and Royal Castle of Warsaw. An extensive monograph accompanies the exhibition, which will next travel to the Musée des Arts décoratifs in Paris, opening in March. The works, organized by Charlotte Vignon, curator of decorative arts at the Frick, are arranged across two rooms by their patron. Among them is the Duchess of Mazarin, who unfortunately died on March 17, 1781 before Gouthière could collect two major invoices, which contributed to his later giving up of assets to his creditors. One of these ruining pieces for the Duchess is on view: a side table with snakes, arrows, foliage, and a central, strikingly lifelike face. It’s now part of the Frick Collection.

And the Frick has another connection to one of the exhibition’s loveliest, yet utilitarian, objects: a 1770 doorknob crafted for Louis XV’s mistress, Madame Du Barry. Once installed as an ornate touch in her Pavilion of Louveciennes, her “D” and “B” initials are formed within a lively myrtle leaf, a symbol of Venus. The painter Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun later recalled that “the locks [at Louveciennes] could be admired as masterpieces of the goldsmith’s art.” Below, a video from the Frick offers a technical explanation of the bronze chasing and gilding process of this doorknob:

The large-scale oil on canvas panels by Jean-Honoré Fragonard that are a permanent installation at the Frick were also created for this now dismantled pavilion, although Du Barry reportedly did not care for his depictions of “The Progress of Love.” However, J. P. Morgan in the 19th century was into them, and after his passing they were acquired by Henry Clay Frick for his mansion on Fifth Avenue, which is today’s Frick Collection. This era of opulence has long had its revivals, with the popularity of Gouthière’s style, after his death, resulting in a large amount of misattributed work — thorough research prior to Virtuoso Gilder at the French Court assured the authorship of the art on view.

Today, lavish gilding is often considered tacky, or an attribute of the so-called “dictator chic” aesthetic, yet it shares the same intention of these 18th-century crafts. Especially adopted by Louis XIV, the Sun King, the gold at Versailles seemed to glow with the divine right that the monarchy believed it possessed. So even if it was likely not a curatorial intent, the examination of Gouthière’s gilding at a moment when the President of the United States is a man with his own 18th-century French decorative arts obsession, is particularly relevant.

A significant aspect of Gouthière’s gilt bronze work is that it wasn’t gold molding, but intended to give the appearance of that purity, which the artist was so skilled at suggesting in his scaly details of serpents writhing above Chinese garden seats repurposed as vases in 1782, or the chased stippling of feathers on two swans on a pair of 1770s vases. Behind each of these objects were patrons convinced of their own right to this wealth, to convey it, no matter the authenticity of materials, down to their doorknobs, even while the mobs were growing outside their gleaming palaces.

Pierre Gouthière: Virtuoso Gilder at the French Court continues through February 19 at the Frick Collection (1 East 70th Street, Upper East Side, Manhattan).