Portraits from UK's Historic and Obscure Pagan Festivals

Over a thousand years since Christianity rose to dominance in the United Kingdom, pagan traditions continue to thrive.

Over a thousand years since Christianity rose to dominance in the United Kingdom, pagan traditions continue to thrive. Across England, Ireland, and Scotland, people regularly cover themselves in face paint, archaic garb, and even 11,000 thistle burrs to participate in rituals and processions whose Celtic, Germanic, and early Christian origins are often now too obscure to explain.

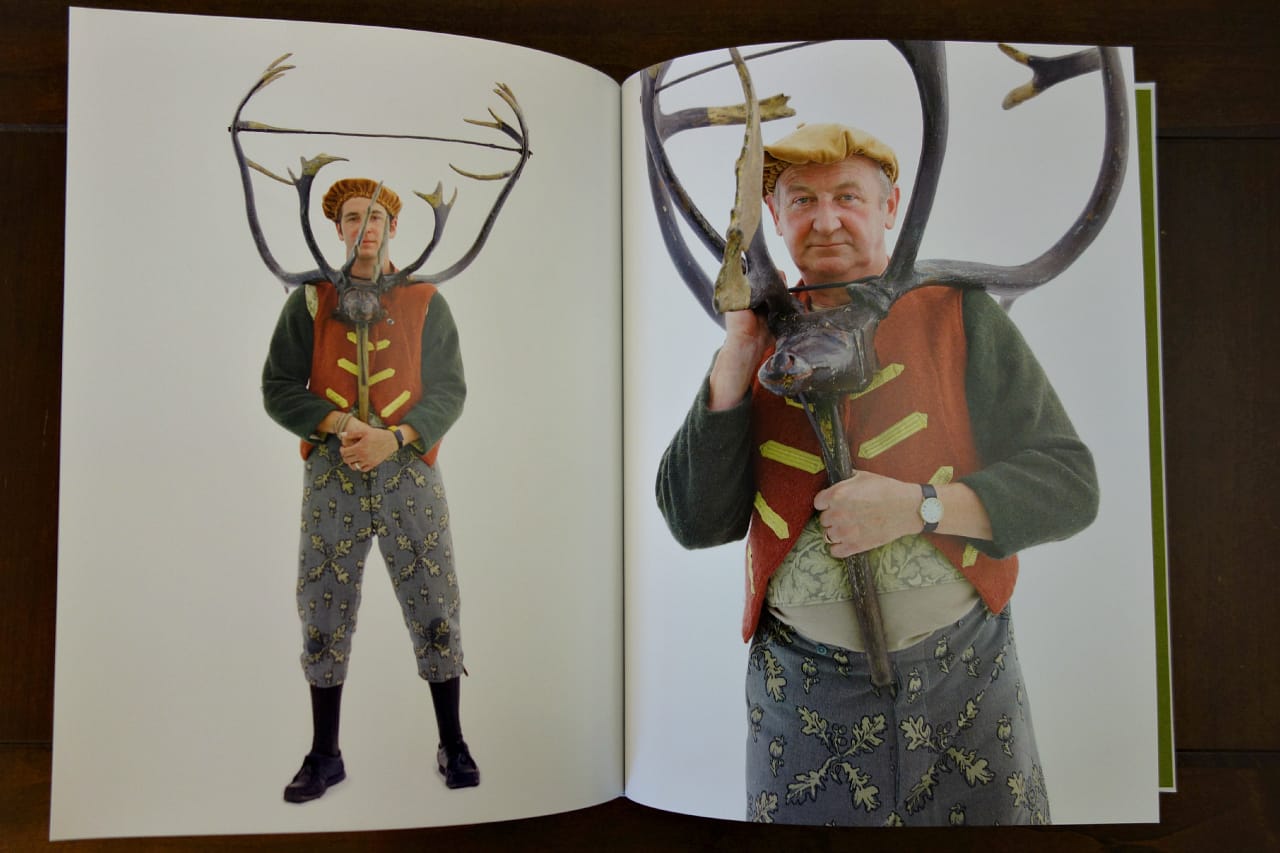

Photographer Henry Bourne began documenting these curious customs in 2009, and this month Arcadia Britannica: A Modern British Folklore Portrait published by Thames & Hudson includes 125 of his portraits. Bourne was in part inspired by the 19th-century photography of Sir Benjamin Stone, who was equally drawn to odd happenings like the Northumberland Baal Fires with their incendiary rites and the May Day festivals with elaborate flora outfits.

He was also influenced by Irving Penn’s mid-century portraits of residents of Cuzco in the Peruvian Andes, documenting their distinctive garb against a plain grey backdrop. Bourne traveled to different festivals and set up his tent with a white backdrop, and outside of the context of the greater spectacle the strange details of the costumes that mix the old and the new come clearly into focus.

“The wheel of the year features over seven hundred folklore events in the UK, for the most part linked to a specific season or date,” art director and Museum of British Folklore director Simon Costin, who often accompanied Bourne, writes in an introduction. He notes that with church attendance in decline “many of the events have disappeared or have lost some of their meaning.” However, those meanings are often long severed from any sort of concrete origin. For example, he relates how one of the reindeer antlers used in the Abbots Bromley Horn Dance in Staffordshire had a piece break off in 1976, which was then dated to 1065 CE. That’s after the extinction of reindeer in the region, adding the question of where the horns came from to why people hoist them yearly in a dance.

“If anyone feels that modern life has left these rituals stranded as irrelevant archaisms or cast them into reaches unfathomable to any but the most fanatical, he or she need only glance at the newspapers,” curator and writer Robin Muir argues in her forward. She cites the incredible endurance of the Burry Man in Edinburgh, where a local man is covered head to food with spiky, insect-attracting burrs so that two attendants are needed to hold up his arms while he roams the city for sips of whisky. Back in 2014, a Burry Man was hospitalized when a piece of his costume became lodged in his eye.

More serious than such wardrobe hazards is that a few of the festivals traditionally have participants paint their faces black, something that got Prime Minister David Cameron into a bit of controversy when he posed with one group, the Coco-nutters. Some of the origins of these outfits may be mining or chimney sweeping rather that racist blackface, but in some instances that appears unlikely — two people photographed for the Lewes Borough Bonfire Society were also sporting animal pelts and feathered headdresses adorned with skulls.

Considering the portrait sitters are by and large white, it’s something Arcadia Britannica could have explored more deeply outside the mentions in the two essays, but Bourne’s photographs are presented without comment.

Selections from Arcadia Britannica are below, where the pagan past endures in modern folklore.

Arcadia Britannica: A Modern British Folklore Portrait by Henry Bourne is out this month from Thames & Hudson.