Queer Arab Artists on Their Own Terms

Across two galleries in Manhattan, eight artists and collectives flout the weaponization of their identities to justify violence, instead presenting a vision of belonging and reclaimed lineages.

Upon entering Participant Inc. gallery in Manhattan's Chinatown, a pitch-black embrace invites us find one another in the dark. As our eyesight adjusts, a constellation of works illuminates [minna|منا]of us, a group exhibition open through March 15 featuring queer artists of the Palestinian, Jordanian, Lebanese, Syrian, and Egyptian diasporas. Wafts of burning incense mingle with the instrumentals of a commissioned sound mix by Palestinian musician Falyakon to direct visitors through the show, which Palestinian-Jordanian-Egyptian artist Ridikkuluz curated as a space for anti-colonial futurism across tradition and geography.

“The show is about giving the pen back to the writer, giving the paintbrush back to the artist, during this time of genocide,” Ridikkuluz told Hyperallergic in an interview at the gallery. “And when there's been so much censorship, these are artists that might not have been able to do this anywhere else.”

While [minna|منا]of us centers the narratives of queer artists with roots in the region, Ridikkuluz emphasized that those identity markers are not the exhibition's sole focus. The show comes at a time when the oppression of LGBTQ+ Arabs has been weaponized in support of Israel's genocide in Gaza, but it intentionally avoids dwelling on collective trauma.

“Regarding the work that I'm showing, people are always asking me, 'Is your family okay with you being trans?' And I really hate that question in a way,” said Elias Rischmawi, a multimedia artist of Palestinian descent. “I show that I'm so connected with my family through my work. Even if we might be distant, or if we have our differences, I'm still celebrated in my community. And it's like a 'fuck you' to that.”

In the exhibition, Rischmawi presents five archival and contemporary photographs depicting family members in Florida, Beit Sahour in the Occupied West Bank, and San Fernando in Chile. In one diptych, a black-and-white photo shows Rischmawi laying their head on their mother's knee, mirroring the adjacent print of a now-lost painting of the artist's mother and great-grandmother in a similar pose.

Similarly reaching into tradition and lineage, queer identical twins André and Evan Lenox-Samour work collaboratively and meticulously with mother of pearl — a reference to intricate family heirlooms that were safeguarded during the Nakba in Palestine. Their shimmering sculptures pay homage to these precious objects and to the storied mother-of-pearl artisans of the Hazboun family in Bethlehem through motifs like arrows and eight-pointed stars, evoking themes of direction, migration, and placelessness.

The exhibition also includes a mixed-media installation by trans Palestinian artist Xaytun Ennasr, a stone bust referencing Egyptian funerary sculptures by Alex Khalifa, and a contemplative film, “Congress of Idoling Persons” (2021), by Beirut-born artist Basyma Saad.

On the next floor, home to exhibition co-organizer SALMA gallery, hangs Syrian-Canadian artist Anka Kassabji's poised self-portrait. Relaxing in an icy bath, she gazes over her shoulder with authority while her legs, crossed at the ankle, jut out from the water — resembling the neck of a chilled champagne bottle.

“I may be not as confident as my paintings are, but I always want to represent extremely fierce feminine energy in my work,” she told Hyperallergic. “The work has this effect of really icy weather that can be uncomfortable, but I'm still very much in control, and I wanted to celebrate what I've achieved throughout those hard times.”

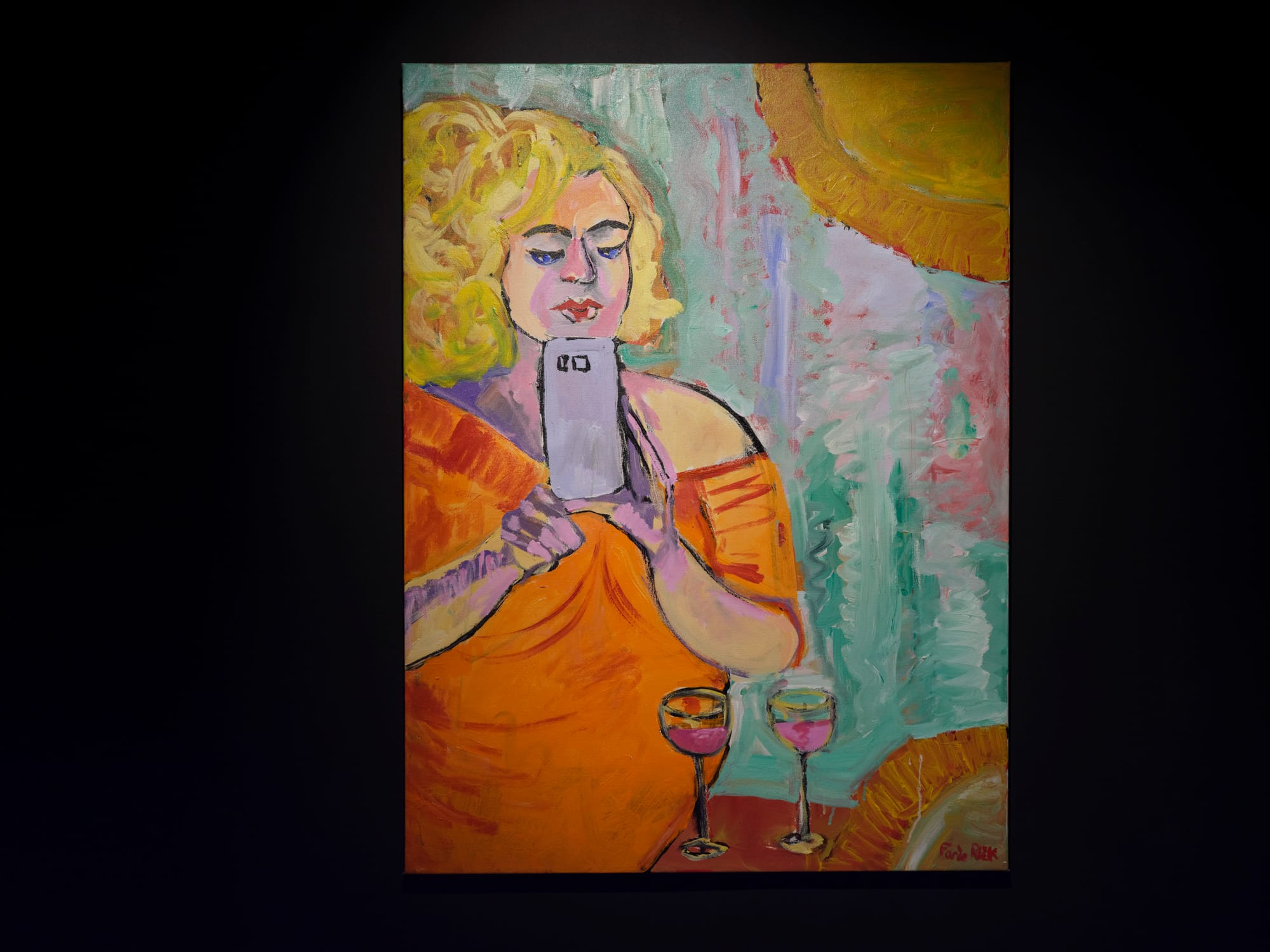

Across the gallery hang three vibrant paintings by Palestinian-Jordanian artist Fares Rizk that portray his better-known alter ego: Sultana, New York's first Palestinian drag queen. Blonde and buxom, Sultana day-dreams, eats knafeh, and snaps a selfie before date night with her devoted boyfriend — channeling her vivacity from the stage to the canvas.

Rizk, who has lived in New York for 40 years and debuted Sultana in 1996, told Hyperallergic that his mother heavily encouraged his interests in dance, art, and makeup. Though his siblings have been less supportive, Rizk says that nothing can get between Sultana and her place under the spotlight.

“When I belly-dance on stage and the people clap and the light is on me, it's healing all the anxiety,” Rizk said.