Rediscovering the Music of the Age of Caravaggio

The aural history of the 16th to 17th century resonates through the Metropolitan Museum of Art's Painting Music in the Age of Caravaggio.

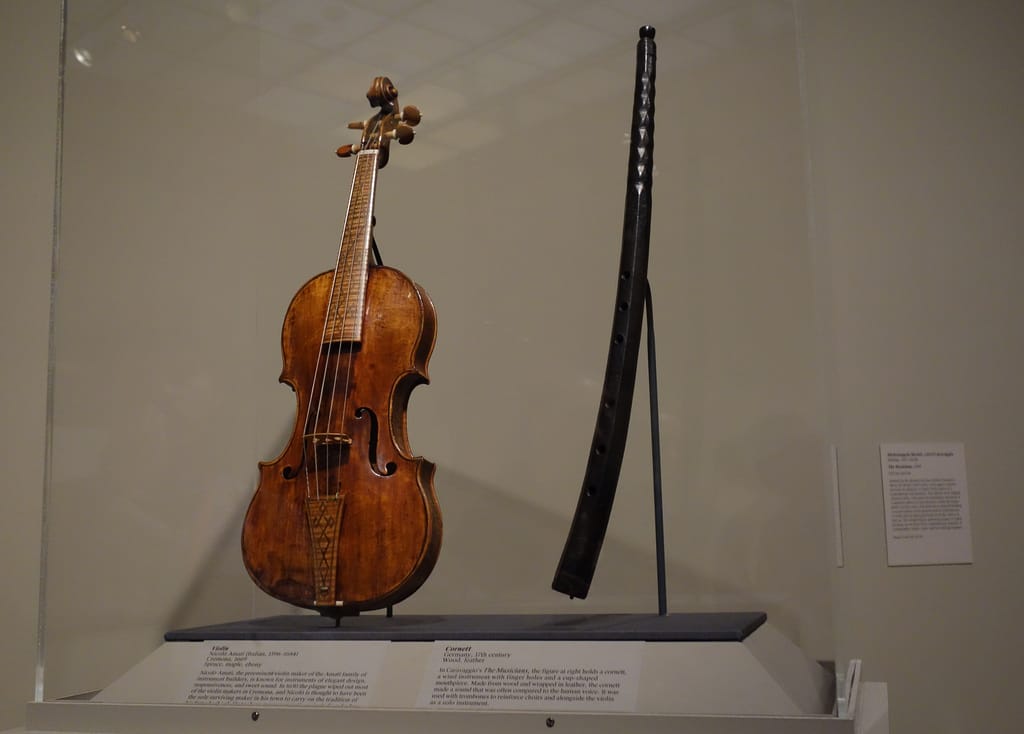

The aural history of the 16th to 17th century resonates through the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Painting Music in the Age of Caravaggio. Lutes, a plague-surviving violin maker, and songbird charming flutes join three paintings that depict the musical instruments, one by Caravaggio and the others by contemporaries Valentin de Boulogne and Laurent de La Hyre.

It’s a modest exhibition, just overtaking a single small room amidst the larger European art galleries. With an in-gallery soundtrack performed on the Met’s lutes, it’s a compact portrait of music at a time of evolution. For centuries in Europe, the lute was king. Originally inspired by the West Asian ud, whose own history goes back to Mesopotamia, the lute was long unrivaled by any other instrument in popularity. As Jayson Dobney, associate curator and administrator in the Met’s Department of Musical Instruments, writes in a blog post on the exhibition, the “seventeenth century brought great changes in musical styles, with singers and violinists becoming the dominant soloists. The lute became a part of the continuo group, and played alongside instruments that could play basso continuo — the bass line and tonal harmonies that accompanied soloists.”

The lute is present in each painting, either being tuned or played, but is often joined by other instruments from this new tonal group. In the highlight — Caravaggio’s luminous, classically-inspired “The Musicians” (1595) — the artist paints himself with a cornett, which has a sonorous quality like the human voice, while a singer studies his music and a lute player sits before Cupid idly plucking at grapes in the background. In the foreground a violin rests on tousled sheet music. Meanwhile in Laurent de La Hyre’s “Allegory of Music” (1649), a woman apparently so concentrated on tuning her long-necked theorbo she hasn’t noticed her dress falling open, is surrounded by a band of instruments including a violin, bass recorder, and flageolets. A feathery companion sits near her shoulder, as the ivory flageolet, a type of small recorder, was by the 18th century being used to teach songs to songbirds. Valentin de Boulogne’s “The Lute Player” (1626) contrasts with a sole player in somber hues strumming distractedly.

Contained in glass cases cornering the paintings, the instruments themselves are consistently stunning, from the lutes with their wood stave bodies like the hulls of small ships, to the elegantly shaped body of a 1669 violin. This instrument in particular was made by famed luthier Nicola Amati. Not only a great craftsman, he had the good fortune to survive a 1610 plague that killed most other Cremona violin makers, leaving him the sole survivor to carry on the trade. Alas, Painting Music in the Age of Caravaggio‘s light recordings of lutes in the gallery doesn’t also include these other instruments, so viewers just have to imagine their timbres.

When the works in Painting Music in the Age of Caravaggio were created, viewers would have had a response that evoked the sound of the instruments. We don’t have this same knowledge of music now, but through the exhibition there is an auditory portal that places the paintings into their sonic context.

Painting Music in the Age of Caravaggio continues at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (1000 5th Avenue, Upper East Side, Manhattan) through April 5.